Mónica Degen

Steps to move and change

Steps can be both those we take every day, one foot after the other, or those material constructions that take us somewhere else. Both seem ordinary, almost banal, but steps entail movement and change. We take steps to reach a destination; we walk up or down steps as they allow us to reach a different place – in both cases they lead to transformation.

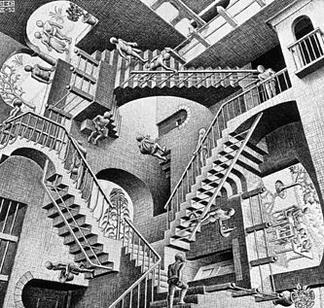

Steps as material conductors to different elevations or buildings are also connecting entities since they allow access to various spaces. Escher’s (1953) famous painting Relativity comes to mind. Similarly dressed people ascending and descending stairs, minding their own business, linked yet separate. The viewer wonders where each staircase will lead. Does it matter?

steps seem to symbolize a transformation or change

Steps are possibly the most symbolic features or even landmarks of cities. Thus, important buildings often have grand steps leading up to their entrance to exercise visceral power on those struggling to ascend the building while they look upwards, while simultaneously transferring power to those descending and looking downwards. Steps also famously feature in films. One immediately thinks of Battleship Potemkin’s (1925) famous scene of the carnage that occurs in Odessa, the Spanish Steps featured in Roman Holiday (1953) with Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck, the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art in Rocky (1976), or more recently the steps featured in the Korean film Parasite (2019) that connect both the poor and rich neighborhoods and the basement and living rooms inside the house. In all these films, steps seem to symbolize a transformation or change – a journey, yet also suspense and a sense of the unknown. As Bachelard (2014) points out, the stairs to the basement are perceived to be leading down to the dark side of our subconscious, while the stairs leading up to the attic are perceived to be more positively linked to childhood memories.

Taking steps in our everyday lives also entails markers of journeys or the passing of time. If we retrace the steps we have taken, we could possibly retrace our lives, the experiences and places we have encountered. A person’s life can be understood by tracing the steps taken; whether it is through leisurely walking or walking as a necessity. It strikes me that, ironically, those who accumulate the most steps – the wanderer, the homeless, the refugee – are often viewed with suspicion, while those who take fewer steps (literally and symbolically) – those who, so to speak, “stay in place” – are cherished for their stability and apparent rootedness. Yet, those who have walked, moved, and are able to compare, contrast, and evaluate different places are often deemed negatively as placeless or, in Theresa’s May (2016) critical words, “citizens of nowhere”.

Nevertheless, steps are essential to movement, to advancing, learning, and knowing. It always strikes me how many of us step out of our houses to routinely trace the same routes and walkways. Most urban dwellers do not know their city but stick to their familiar neighborhoods’ routes to school, work, restaurants, always staying within their known social world. Steps ought to entail, exploring and adventure: making new connections, or, maybe, also, sometimes need to be about pausing, feeling, and gaining awareness of our surroundings.

References:

Bachelard, Gaston. 2014. The Poetics of Space. London: Penguin.

May, Theresa. 2016. Conservative Party Conference Speech, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/full-text-theresa-may-s-conference-speech/ (accessed 15/08/24).

Niamh Ní Bhroin

Every step we take

(The Police, 1983)

Every step you take

I’ll be watching you

Back in 1983 when The Police released their persistent chart hit “Every Breath You Take”, Mark Zuckerberg was not even born. The genesis of Zuboff’s surveillance capitalism was literally in embryo. Zuckerberg came to the pre-metaversal world the following Orwellian year – 1984. Perhaps baby Zuckerberg was overly exposed to this chart hit while in his mother’s womb. In any event, Sting and his band mates could certainly not have foreseen the eerie significance that their song lyrics would have four decades later. They presumably thought that the idea of being so consumed with what another person was doing was somehow romantic.

Forty years later, literally every step we take is being watched. Connected to the mobile internet via the telephones in our pockets or the watches on our hands, our steps are tracked, recorded as data points, and stored for behavioral analysis and profiling. How we move, where we go, and who and what we spend our time with are valuable units of information that inform media platforms and advertising corporations about our preferences, our means, and ultimately how likely it is that we will purchase their products and services. Usually, we do not know who or what is watching us at any point in time as we walk around in our neoliberal lives.

The culture of self-tracking prompts questions about the number and nature of the steps we take. Are we the kind of person who takes the recommended 10,000 steps every day? Are we, for whatever reason, more or less physically active? Where do we usually move around? Do we have predictable lives which take us to the same mundane locations during the course of the week (home, work, daycare/school, supermarket, extracurricular activities, etc.)? Do we have a regular jogging route? Are we usually moving around in the same town, city, or rural area? Do we travel internationally? If so, how often?

These quantified representations provide us with useful information about our personal health, while at the same time complicating our perception and understanding of our sensory experiences.

Our steps, recorded as data, tell interesting stories about our lives. But these stories are not often shared with or read by our family and friends. They are usually used as analytical tools by corporations who hungrily feed the data we produce into their commercial machines. But these stories are also used by us as individuals (Have I moved enough today? Should I go for another walk?). These quantified representations provide us with useful information about our personal health, while at the same time complicating our perception and understanding of our sensory experiences.

Our ability to take steps, once considered as one of the most significant milestones in the development of human children, lays a new foundation for data-driven geo-tagging ankle bracelets, determining our confinement within commercially framed eco-systems. This new significance of our steps fundamentally changes what it means to be human.