Rachel E. Black 2012. Porta Palazzo: The Anthropology of an Italian Market. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. 232 pp. ISBN 978-0-8122-4406-9

This is the second installment of Allegra’s Special Review section on Rachel Black’s book. Read the first part here.

If ‘marketisation’ is one of the key phenomena of our neoliberal times, the term thus suggests the generation of raw units of transaction, and belies its origin in that other kind of market – a physical place of face-to-face interaction. The anonymous purchases that feed corporate retail, so-called online ‘marketplaces’ and the virtual relations that make up ‘the market’, the godlike agency that looms over our bulimic financial services sector, have their roots in another field of exchange: the traditional marketplaces that thrived as centres of social and commercial life for centuries, in all civilisations in which trade played an important part (which some might say means all civilisations tout court). Indeed, for most of mankind’s history since the rise of agriculture and complex societies, this social and commercial life revolved primarily around transactions involving food and drink.

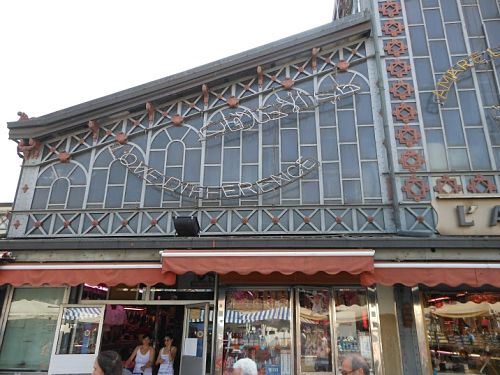

In this light it is appropriate that the study of traditional markets is a classic topic in anthropology, but, as Rachel Black points out, it needs to be revisited ‘in the face of drastic changes in food provisioning and eating habits in Europe’ (p.4). One might add that these changes threaten to become even more dramatic in the context of the current secretive negotiations between the USA and the European Union over TTIP, the US-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which threatens to undermine Europe’s unique regulatory framework protecting society and the environment from corporate interests (Bové and Luneau 2014). Traditional markets, though inefficient compared to other modes of commodity distribution, have other valuable characteristics, and it is precisely these that Black sets out to document through her detailed study of Porta Palazzo market in Turin, one of the largest and most thriving of Europe’s surviving urban street markets.

In this light it is appropriate that the study of traditional markets is a classic topic in anthropology, but, as Rachel Black points out, it needs to be revisited ‘in the face of drastic changes in food provisioning and eating habits in Europe’ (p.4). One might add that these changes threaten to become even more dramatic in the context of the current secretive negotiations between the USA and the European Union over TTIP, the US-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which threatens to undermine Europe’s unique regulatory framework protecting society and the environment from corporate interests (Bové and Luneau 2014). Traditional markets, though inefficient compared to other modes of commodity distribution, have other valuable characteristics, and it is precisely these that Black sets out to document through her detailed study of Porta Palazzo market in Turin, one of the largest and most thriving of Europe’s surviving urban street markets.

While the book’s division into chapters lays out its key themes (history, space, morality, migration, ‘ethnogastronomic tourism’ and ‘local food’), it is really the way in which these and other topics are interwoven throughout the text that is most compelling. By working on different stalls (a sweet stall, a Moroccan vegetable stall), and joining the regular hangers-on at an especially convivial cheese stall in the farmers’ market, Black came to understand the different points of view of the actors whose lives revolve around this place, at once both a hub of social life and a centre of commerce. She succeeds in bringing them to life with disarming frankness and simplicity of expression.

One of the most powerful aspects of the book is the way it portrays the lives of migrants.

As the historical section shows, markets have traditionally been at the margins of cities, at crossroads, and have always been meeting places for people of different origins.

In this light it comes as less of a surprise that markets are often one of the first places to which migrants come to make acquaintances, find work, and indeed to buy and sell things themselves. We learn how the Moroccan vendors are a fully established part of the scene (as even the new arrivals, the informal, ambulant Moroccan mint sellers are in their own way); yet they experience tensions and conflicts with Italian vendors – and we see how these tensions seem above all to be revealed when architectural and organisational improvements are introduced by the municipal authorities.

We are treated to sensitive accounts of the ways in which criteria of taste and identity are articulated, as vendors attempt, with often provocative and ‘carnivalesque’ displays, to ‘seduce’ potential clients. We can literally taste the outcomes of discussions of recipes as these are provided at the end of chapters so that readers can cook them for themselves. We discover why the market is a haven for the elderly – not only because it is a stimulating place to go and buy fresh things at good prices in a convivial environment, but for the more unhappy reason that the scraps left over at the end of the day provide for those who have to scavenge for their supper. It is telling that the vendors are mindful of this when they dispose of their unsold wares.

Porta Palazzo is a powerful antidote to the assumption, held by many, that traditional style markets are nothing more than ‘bijou’ tourist attractions for Europeans, or indulgences for ‘foodies’. Certainly such markets exist, and there is at least one in Turin itself.

But popular markets like Porta Palazzo are living traditions that also provide livelihoods and sources of good value, fresh produce to ordinary people.

This is even true of the farmers’ market, which is a distinct space within Porta Palazzo. It is no mere haunt of middle class buongustai, but rather a place where all kinds of people come together to share, understand and even improve traditional ways of cooking, with an informed interest in the people and places that produce ingredients. The farmers themselves are not well-to-do hobby farmers but peasants (including some immigrants such as an African woman who specialises in live chickens), and it is the connections between regional cooking and living traditions of food production that bind clients to vendors here.

Piemonte, the region in which Turin is situated, was where the Slow Food movement was founded by Carlo Petrini, who contributes a preface to the book. I make these points because Slow Food has faced similar misunderstandings from members of a wider urban public less sensitive to the vibrancy of the embattled popular and peasant traditions of cooking and food production that the movement seeks to defend (not only in Europe but also in the global South).

As Porto Palazzo also makes clear, those who are part of these traditions do not seek merely to preserve them as they are, but to change and improve them with an often surprising openness to different influences

– always, however on a human level: ‘improvement’ here should not of course be taken in the Enlightenment sense (which was applied in particular to agriculture) of increasing efficiency, but instead as signifying ‘making (taste) even better’.

This account of a very human economy has wide reaching implications, and it comes as a slight surprise that there is no reference to recent work on this subject (Hart, Laville and Cattani 2010), although other works in a similar spirit are cited. But this is a minor criticism: to write an ethnography of a market is an opportunity to do precisely what ethnography is so good for: to demonstrate through the detailed narrative of the mundane what is important about a set of facts and observations which, taken on their own, might seem of little consequence.

The best and most lasting ethnographies rest on their success in showing rather than telling, in bringing a place and a set of social relations to life in a way that enables the reader to understand at a profound and pre-theoretical level something more general. This is exactly what Porta Palazzo achieves.

The prose is unassuming, unpretentious – in the first pages, I occasionally thought it naïve in style. Some errors in Italian phrases must be blamed on the editors. But the cumulative effect is something else. Page by page, chapter by chapter, Rachel Black composes an at once deeply personal and yet thoroughly rounded portrait of one of the most important surviving street markets in the world.

References

Bové, J. and G. Luneau 2014. Hold Up à Bruxelles: Les Lobbies au Coeur de l’Europe. Paris: La Découverte.

Hart, K., J-L. Laville and A. Cattani 2010. The Human Economy. Cambridge: Polity

The photographs in this article are from Constanza Curro’s personal photos.