Monarch migration and the making of North America

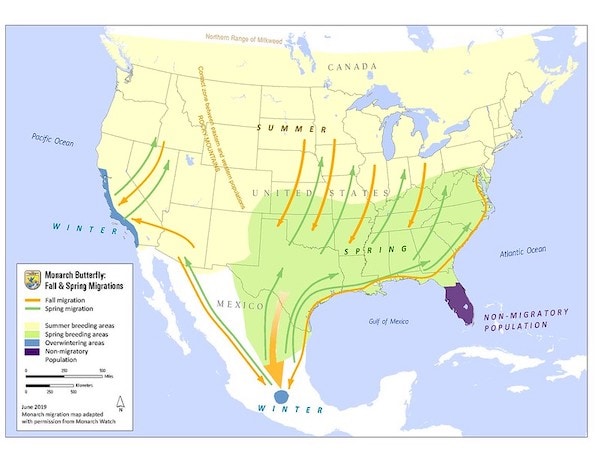

At the end of each summer, the northern prairies and Great Lakes regions of North America host a new generation of monarch butterflies. After their last metamorphosis in late fall, the butterflies travel over 4,000km to what we now call Mexico. In their warmer winter habitat, they form colossal raindrop-shaped clusters of thousands of butterflies suspended from a single tree species, the oyamel. Monarchs there enter a semi-dormant state for four months, surviving on little food. Each subsequent migratory generation performs this heroic feat without directly ‘learning’ the route from their progenitors. Despite their iconic standing across other North American insects, monarchs today are threatened by decline. Conservation scientists continue to debate the specific reasons for their reduced population; however, what is certain is that monarchs lack the healthy interconnected continental habitat they need to thrive in large numbers.

My multispecies ethnography with the monarch reveals interconnected geographies of colonial dispossession that threaten both human and monarch lives. Two examples of human and monarch displacements occurring in ‘sister’ national parks created to protect monarch habitat, show how Indigenous groups’ ways of relating to the monarch in these sites – and beyond the confines of national parks – may contain keys to a better set of environmental ethics for the continent. This multispecies lens carefully engages with Indigenous ecological practices in their current complexity. It re-visits the idea of ‘North America’ as a multispecies spatiality that urgently needs to repair the overlapping violence towards Indigenous populations and other earth beings.

What is certain is that monarchs lack the healthy interconnected continental habitat they need.

A band without a land

The monarch butterfly breeds in northern North American prairie habitat, relying on a single host plant popularly known as milkweed. The insect lays eggs on it, feeds from it as caterpillar, and often hangs off of it as a pupa enclosed in a cocoon, until it ecloses – or emerges as a young butterfly – and migrates in the fall. The monarch’s original prairie habitat is today aptly referred to as the ‘Corn Belt’, having been appropriated from the area’s Indigenous peoples. The dystopic agribusiness (rather than agriculture) landscape, which cuts across the Canada-US border, is now primarily a pesticide and herbicide-saturated corn monocrop. Chemicals originally developed for war economies are now entrenched in our food and trade systems, affecting the host plant of the monarch.

Chemicals originally developed for war economies are now entrenched in our food and trade systems.

This monocrop landscape is also built on displacements of humans, specifically the dispossession of this region’s First Nations who share Anishinaabe ancestry. With European settlement, these groups were relocated far away from their original territories to more confined areas (‘reserves’), or in some cases made landless – as was the case of Point Pelee’s Caldwell band, a Chippewa- and Pottawatomi-origin group that traditionally migrated seasonally, sharing ecological niches and migratory patterns with the monarch. That band’s displacement disrupted its longstanding relationships with the prairie and lower savannah habitat, and undermined its relational ecological knowledge systems which historically nurtured an abundance of insects, including monarchs (Betasamosake Simpson 2019).

Monarchs, threatened not only by agribusiness but also climate change and habitat loss, are today under ‘protection’ measures across North America. In Canada, its conservation epicenter is Point Pelee National Park. A peninsula on Lake Erie (one of the four Great Lakes), and a Canada-US border crossing, Pelee’s specific ecology and land formation is a magnet for multitudes of birds and butterflies. It also attracts flocks of tourists seeking to explore the ‘tip of Canada’ and watch the monarch’s fall migration. Sharing this peninsular home with the monarch historically were the Chippewa and Potawatomi Indigenous people.

Some of Pelee’s Indigenous residents left to fight settler encroachment in the 1700s. Others left to participate in the War of 1812, the outcomes of which defined the current Canada-US border. In 1918, the remaining Caldwell band members were expelled to create a National Park. At the time, it was one of the first conservation parks in the country. Today, it is Canada’s smallest and most biologically diverse.

Jane Peters (pseudonym), a First Nations woman appointed chronicler for the Caldwell Band, recalls these displacements vividly. Her family lived at Pelee before their eviction. Her account, however, begins much earlier, in the late eighteenth century. My family’s ancestors battled with Chief Pontiac, she shares. In 1763, Chief Pontiac organized an inter-tribal rebellion that managed to lay siege t the British army in present-day Detroit (south of Pelee) for six months. Pelee became a strategic point in this struggle. Band members assaulted British ships and successfully halted a rescue mission aiming to end the siege. The Indigenous victory, however, was short-lived. The uprising was eventually suffocated, and by 1792, the Mckee Treaty endowed Pelee to the English Crown that officially designated it a Crown Naval Reserve. According to Pelee’s First Nations, this designation occurred without their consultation.

Upon return, they were allowed to live in Pelee as renters – while surveyors often labeled them as trespassers – and were forced to fight in the War of 1812. Forced to choose between two evils, in the words of Dylan (pseudonym), a young band member and fellow community chronicler. Here he refers to the choice between the British, for whom his people fought, and the rivaling Americans. He continues: We took up arms, and if we had had retreated right along with the British troops, we would all be looking at the Americans today. The Caldwell Band’s name is a tribute to this military intervention, which was led by a British commander of that last name – We would have different borders, he maintains.

Both Dylan and Jane emphasize the violence inflicted on their people across centuries, but also their people’s agency. They stress how their people were responsible for creating Pelee’s current Canadian border even when a National border challenged their seasonal movement across the Great Lakes. Just as Pelee is a summer destination for monarchs, then, it was also one for humans. Dylan pointed out to a woven art piece hanging from the wall. The textile narrated the story of the region: humans in canoes, turtles, birds and monarchs passing through. Sharing the abundancy, gifted by the water, he commented.

Just as Pelee is a summer destination for monarchs, then, it was also one for humans.

When Dylan and Jane’s people were forced to leave their ancestral summer home, they did not do so without resistance. In protest of its conservation status, they re-occupied Pelee in 1920 but were ultimately evicted and left landless for the next 100 years. – The Mounties [Canadian police] went in and burned out our homes, took my family out and left us without formal recognition nor a land endowment, Jane tells me.

However, as the surrounding corn monocrop economy encircled Pelee, the park has faced significant challenges in protecting the monarch’s habitat. Ironically, an area that seeks to protect the monarch also hosts one of the key drivers of its decline: agribusiness with its destructive effects on the butterfly’s host milkweed.

Meanwhile, the Caldwell band has also struggled to retain a home. They remained landless until 2020 (Forester 2020), when they resettled in the park’s vicinity. This was the culmination of over one hundred years of resistance to settler colonial land dispossession. It is too early to say how monarchs will figure into their evolving livelihoods, but band members are not kin to the region’s now dominant agribusiness model. Indeed, one of the reasons that resettlement took so long was that it was opposed by local farm owners, who claimed to ‘fear’ the re-introduction of Indigenous agricultural methods which could allegedly lead to ‘spills’ of the weeds and insects that the monocrop model seeks to eradicate.

Band members are not kin to the region’s now dominant agribusiness model.

A land of correspondences

At the other end of the monarch’s 4,000km journey, in the Michoacán region of what we now call Mexico, lies Pelee’s ‘sister’ park: the UNESCO Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, where the monarchs overwinter. This is also the ancestral home of the Mazahua and Otomí* groups, who like the Caldwell band have faced dispossessions linked to colonialism and conservation. These groups have likely lived with the monarch since precolonial times, but were exiled to the high mountains during the Spanish occupation. This displacement interrupted longstanding land-use practices and traditions and deepened competition for resources. Despite this, communities still practice ancestral land management techniques. These are based on a model of sustainable agroforestry involving a corn-based mixed cropping system in the lower hills, complemented by a communal forest in the upper hills where residents collect forest products, hunt, and engage in ritual activities.

This area received protected designation according to UNESCO’s conservation precepts in 1980 after the monarch migration was pieced together by a joint Canadian and Mexican research team. The group, which was mainly composed of volunteer workers, tagged monarch wings over 25 years and tracked the tagged butterflies to central Mexico. Driven by the discovery of the migratory pattern, the park was initially designed to protect monarchs during their overwinter season. It was later expanded to cover more forest habitat with a permanent hunting and agroforestry ban. Much as conquest and occupation introduced new borders, the creation of the UNESCO reserve imposed a new set of boundaries in this ethnoterritory. The park design posits ‘people-free’ cores and buffer zones which allow some activities. Unlike in Pelee, communities did not lose land ownership, but their interconnected corn milpa (artisanal corn gardens) and forestry systems were disrupted since they could no longer collect resources from or hunt in the upper forest. Forest and agricultural livelihood losses have only been partially offset by tourism revenues from conservation, and the reserve has faced significant resistance from the communities.

In contrast with the view of conservation scientists that saw the monarch as an insect that needed special protection, my interlocutors in the monarch forest describe how they see the monarch as ‘enveloped in’ (envuelta en) the milpa agriculture and as part of a ritualized landscape. The monarch is seen and treated as part of the forest and social life, and not only as a ‘trinational’ insect. The ritual practices of communities engage the monarch as one species in a human-forest-corn tapestry of mutual reciprocity across the lower and upper hills. For example, they perform rituals in the upper hills to petition rain for a good corn harvest downhill. Indigenous relational practices and knowledges also see the monarch as a ‘correspondent’ between different worlds, including between the living and the dead. Carrying the deceased’s souls, monarchs arrive to the reserve’s upper forest each year during the Day of the Dead celebrations (Nov. 2-3).

The park design posits ‘people-free’ cores and buffer zones which allow some activities.

Four months after the Day of the Dead, the departure of the monarchs marks the beginning of the corn harvest season. In this way, monarch migration cycles are coordinated with the artisanal corn harvest and its associated rituals. Even while conservation and political economic changes have increased the importance of livelihood activities other than small scale farming, the milpa remains the central axis of ritual, social, and economic life. It is also connected with the monarch. In some regions of Michoacán, the monarch is called a ‘harvester’ (cosechadora). This image of a ‘harvester’ insect intertwined with human practices across the upper and lower hills stands in stark contrast with the conservation vision of a human-free monarch ‘core’ and peopled ‘buffer’. Yet, conservation is not the only threat to the millenary agricultural and ritual milpa model. Local land management practices also run up against new il/licit economies that have recently expanded into the oyamel forest. These include avocado plantations to satisfy growing demand, which are enabled by illegal logging. Reserve restrictions have contradictorily increased vulnerability to this habitat destruction. With less community presence in the ‘core zone,’ illegal activities have been allowed to flourish (Gonzalez-Duarte 2021).

Carrying the deceased’s souls, monarchs arrive to the reserve’s upper forest each year during the Day of the Dead celebrations.

As in Pelee, the people of this reserve have resisted dispossession. Initially, they hotly contested the Western speciesist vision that prioritized the conservation of a single insect at the expense of other animals and humans. Yet, today, the monarch is mobilized as part of a strategy to achieve greater self-management of their territory and to fight ‘il/licit’ practices. Indigenous groups are advancing self-government and struggling for direct budgetary control and customary law similar to that of the Indigenous Chiapas or Cherán. Parallelly, there is a resurgence of forms of community-led organization to take care of the monarch forest through community watch and the revitalization of milpa agriculture.

Inspired by the Mazahua and Otomi political achievements and the Caldwell band’s recent land restitution, I pose that caring for this butterfly means addressing the longstanding coloniality underpinning today’s ‘North America’ (Saldaña-Portillo 2016), and which is, unfortunately, perpetuated by conservation practice. Despite these interconnected displacements across North and South, Indigenous groups across the continent continue to fight to retain and reconfigure significant ties with their land. Their struggles and achievements may provide much needed refugia for both monarchs and humans.

[separator type=”space”]

* There are local and used variations of the names of these groups in their languages, for Mazahuas, Jñatrjo/Jñatjo/Jñato, and for Otomies, Nya-Nyu/Hñähñu/Nyot’o.

[separator type=”space”]

References:

Betasamosake Simpson, Leanne. 2019. “Indigenous Knowledge Has Been Warning Us about Climate Change for Centuries.” Pacific Standard, March 2019.

Forester, Brett. 2020. “‘A Band without Land’ No More: After 230-Year Fight, Caldwell First Nation Secures Reserve.” APTN News, November 27, 2020.

Gonzalez-Duarte, Columba. 2021. “Butterflies, Organized Crime, and ‘Sad Trees’: A Critique of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve Program in a Context of Rural Violence.” World Development 142 (June): 105420.

Saldaña-Portillo, María Josefina. 2016. Indian given: Racial Geographies across Mexico and the United States. Latin America Otherwise. Durham: Duke University Press.

Photographs provided by the author.

Point Pelee image and Monarch drawings: archival.