WHAT IS SENSORY MEDIA ANTHROPOLOGY?

With this thread, we want to make a case for what we call sensory media anthropology: an anthropology that de-centers media and meaning-making practices in order to engage with sensuous, practical, and bodily knowledge related to engagements with media (cf. Moores 2017). The past decades have seen an increased mediatization of societies (Hjarvard 2013), accompanied by a growing research interest in media coupled with new methodological opportunities. Over this period, media anthropology has been established as a significant sub-field within anthropology (Pertierra 2018). Media anthropologists have approached the study of media from the perspective of how people engage with media, focusing largely on socio-political implications of media-related practices (Hobart 2010), “linking the richness of everyday social action to broader structures” (Postill and Peterson 2009). Simultaneously, the sensory has been established as a research focus in disciplines across the humanities and social sciences, leading to increasing attention given to the visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory – in short, embodied experiences in the world (Howes 2022; Pink 2015a).

An anthropology of the senses has long been well-established (cf. Classen 1997), yet it is only within the last two decades that a sensory anthropology has developed: as “a ‘re-thought’ anthropology, informed by theories of sensory perception, rather than a sub-discipline exclusively or empirically about the senses” (Pink 2010). Media anthropology is closely related to anthropology of the senses in terms of objects of study, yet not always in terms of focus of study. However, as Pink (2015b: 6) has pointed out, the material and intangible, experiential, and aesthetic qualities of media invite us to attend analytically to the senses. Correspondingly, we see a relevance of further research on media as “immersive, environmental, or bodily-somatic” and on “the consequences of how such media operate on the body and the senses” (Salter 2018). That is, we wish to draw attention to the tremendous potential for what we call sensory media anthropology – an anthropology that connects and brings into sustained dialogue the subfields of sensory anthropology and media anthropology in order to facilitate an integrated theorization of media and the sensory and advance the methodological approaches to sensory ethnographic studies related to media practices.

While sensory media anthropology is not a consolidated field, research has emerged that examines relevant issues. Here, we would like to present three relevant strands of research: emplacement and multi-sensoriality, sensory competences, and how we sense differently.

This thematic section grows out of our efforts to explore connections between media anthropology and sensory anthropology and expand the conversations between the subfields, particularly through establishing the EASA Sensory Media Anthropology network. Many of the contributors to this thematic thread have been part of our workshop series leading up to the establishment of the network, while others have joined along the way and added new energy and insights. In our invitation for contributions, we encouraged authors to be both political and playful, both poetic and theorizing, in an attempt to create the type of knowledge that usually falls through the cracks of academic publishing. Both media and the sensory are political, yet often in subtle and overlooked ways. We wish to call attention to epistemological approaches to different sensory modalities and perceptions in order to nuance understandings of the diversity of media users and experiences that go well beyond individual and cultural approaches to media engagements. We furthermore aim to highlight that despite certain senses being prioritized in relation to knowledge-production, all senses produce knowledge. Thus, sensory media anthropology generates new angles on questions about privilege, race, gender, able-bodiedness, and the production of difference, allowing a layered understanding of inequalities that are often exacerbated in the entanglements between media and the sensory. We thus also want to join the recent call by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård (2023) for acknowledging relations between theorizing and the theorizing body.

While sensory media anthropology is not a consolidated field, research has emerged that examines relevant issues. Here, we would like to present three relevant strands of research: emplacement and multi-sensoriality, sensory competences, and how we sense differently.

Emplacement and multi-sensoriality

Attending to media through the senses (and to the senses through media) is also a matter of seeing the media as part of the sensory-embodied and affective routines of everyday life (Pink and Leder Mackley 2013). This is not to suggest that all spaces are media-saturated, but that media could potentially be a part of them, or could play a role by not being there. Media can be seen as a form of placemaking (Mollerup 2020). Thinking with violence can help unfold this point. That is, violence makes clear how media do not remove us from the phenomenological world however sensorily immersed we might feel. One might be vicariously traumatized by sights and sounds, yet not be hit by bombs, bullets, and teargas. And equally, one is not removed from sites of violence by “being online” or engaging with media in other ways. What is crucial, then, is that whatever our media engagements are, we engage with media emplaced in the phenomenological world. Our sensory perceptions of media are multi-sensorily entangled with our surroundings, whether these are a revolution (Mollerup and Gaber 2015) or processes of urban redevelopment increasingly mediated through digital technologies (Degen and Rose 2022e). Pink (2011) has suggested that images do not exclusively “belong” to the visual sense. We would extend this argument to media products that are primarily thought to engage with other senses. It is worth asking, then, how our perceptions of media are influenced by how we are immersed in both situated and mediated media environments.

That is, how do we study the senses from a future-oriented perspective? And might AI-assisted image, sound, and text production play a role in this effort?

Sensory competences

Individual, societal, historical, and bodily factors influence not only how we engage with our environment, but also how we perceive it. Sensory competences – the learned, the habitual, the tacit – are often central to how we perceive affordances when engaging with media. The literal “handling” of mobile devices and the manipulation of screen objects with our fingers makes users affectively and haptically involved in the affordances, enablements, and constraints of the interface. Yet, while the intimate, tactile, social, and playful nature of mobile interfaces has become a key focus of media research, there has been limited ethnographic analysis of the way these devices are deeply embedded within the communicative and spatial organization of domesticity. These new “techniques of the body” must be accounted for if we are to interpret the complexities and intentionalities of media engagements (Vermaas 2010).

While our being-in-the-world is grounded in our physical and cognitive existence, our being in socio-digital environments is equally reliant on the extent to which we can access and use digital devices. This in turn raises the political economic question of who gets to access which kinds of media devices. Connected to this question we might also ask, what access do we have to data and information gathered and munched on by the non-human sensors and learning machines in our environment (Kytö 2020)? The conversations we have had in our network have explored how memory, experiences, and sensory competencies impact sensory engagements with media. We have also pondered how we might think about – and study – sensory imagination. That is, how do we study the senses from a future-oriented perspective? And might AI-assisted image, sound, and text production play a role in this effort?

How we sense differently

Sensory media anthropology must necessarily grapple with how people sense and perceive differently. Apler (2018) has proposed the term “inclusive sensory ethnography” to draw attention to greater neurodiversity in how humans process sensory input related to media engagements. This attention to neurodiversity is a significant acknowledgement of the breadth of sensory perceptions that is not limited to people who can be described as neurodiverse. Herman (2016) reminds us that vision begins in the retina. The retina is not a passive pathway for sensory inputs, but an active part of the brain itself. What Herman shows, then, is that we do not simply see with our eyes and subsequently digest sensory input with our brains. Rather, we see with our brains, and what we understand we see does not simply supersede the sight, but in important ways precedes it. That is, when we look at images, what we see is informed not only by what is present in front of our eyes, but also by our memory and how we have learned to see (cf. Balcetis 2023). Thus, for instance, two people looking at the same image can literally see very different things. This can have severe consequences; for instance, when images are presented as evidence in courts or presented to broader audiences in the interest of social justice (cf. Kahan, Hoffman, and Braman 2009).

A similar discussion is relevant regarding all sensory modalities. Aural diversity (Drever and Hugill 2023) contests the idea of normative listening experience and promotes awareness of its nuances. A simplistic categorization of normal hearing/hard of hearing/deaf does not represent the reality in peoples’ listening abilities, nor its changing qualities. Our age and the inevitable change in all our perceptive abilities affect our relationship with our environment that is increasingly shaped through digital technologies (Järviluoma and Murray 2023). Another aspect of how media is present in different sensing abilities is the use of personal senso-neural prosthesis that network in the same digital environments as media technology, with the same logic of data accumulation and secondary agency (Kytö 2022). A key question to ask, then, is to what extent the diversity of abilities of various user groups influences the extent to which they can interact with various devices in order to participate in societies that are increasingly digitized?

Contributions

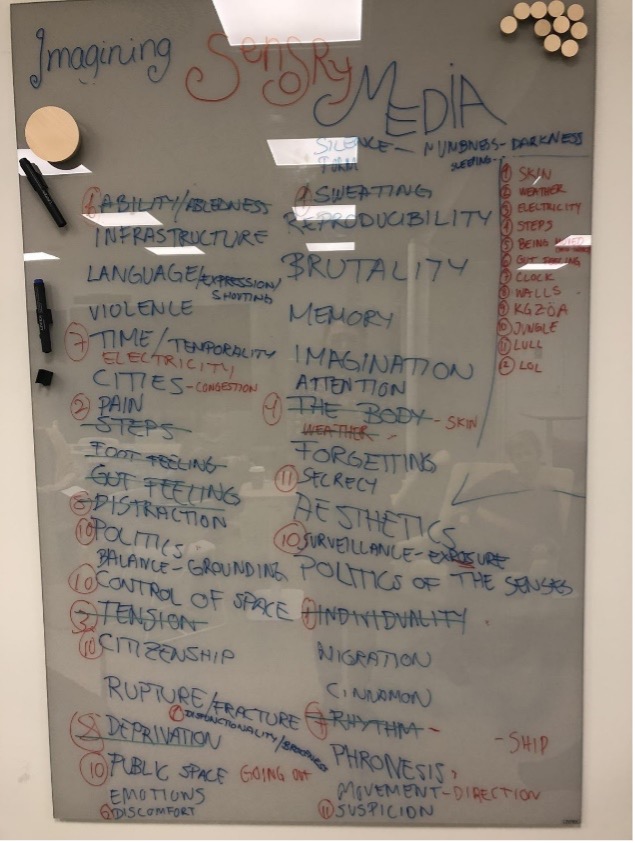

This thematic thread is based on an experimental, collaborative thinking and writing process with workshop participants. During our initial conversations in the network, one thing that became immediately clear was the extent to which we could enrich each other’s work through our divergent perspectives and approaches to issues that mainly shared a broad focus on human engagement with media. For instance, the word electricity could take one member’s mind to asking how digital devices are powered in a warzone and another’s to wondering how smartphones are manipulated by the electricity of human skin making it difficult for elderly to use smartphones since the electricity of skin declines with age.

In the thread, we seek to dwell on this enrichment rather than attempt to narrow the scope of inquiry or try to reach a collective definition. We have thus not worked with a single focus or question in mind, but rather sought cross-fertilization through considering themes. We have been deliberate in our choice of words with our themes. That is, we sought words that did not carry “the theoretical baggage” of concepts, but rather had an openness and un-determinedness to them that we explored from different positions within media anthropology, sensory anthropology, and, of course, sensory media anthropology. This allowed us to engender a conversation that was not restricted by divergent sub-disciplinary conceptualizations of terms or exclusivity in being directed at a limited target audience. Hence, in collaboration with workshop participants, we have selected eight themes that intersect with our diverse work with media and the sensory, without these themes necessarily occupying a central position in our work. These themes include: skin, weather, electricity, steps, moved, gut feeling, walls, and clocks. Importantly, these themes bring out very distinct connotations among the various network members, yet they also allow for a conversation across these differences.

The thread consists of a rich and varied collection that not only draws the contours of sensory media anthropology, but also plays with various formats to engage the “reader”. In actuality, “senser” is a more apt term to refer to the audience since the contributions invite different kinds of sensory engagements well beyond reading, namely through sound, pictures, video, and bodily positioning.

Under the theme skin, Mónica Degen first provides us with a theoretical introduction to skin as the largest and most intimate of our sense organs. Leonardo Custódio then takes us on a multisensorial experience of the politicization of skin through his experiences of Brazilian Baile Funk. Lastly, Nina Grønlykke Mollerup looks at a different form of politicization through visual presentations of skin by considering television news and camera technologies.

Under the theme weather, Niina Oisalo invites us into a visual and auditory reflection on memory, relations, and how to mediate a sense of snow. Meri Kytö takes us on an aurally supported walking trip that traverses both the freezing cold winter of Tampere, Finland, and the commercially-saturated sonic environment of a Christmas time shopping mall to explore sensory connections between materials and media. Finally, Nina Grønlykke Mollerup takes us along through several media-saturated movements and varying weather conditions to propose that weather is a crucial part of the ways in which human beings sense media devices and content as well as the way media devices sense human beings.

Under the theme electricity, Sanne Krogh Groth describes how electricity has had its effect on the genres of electro-acoustic music. In her piece, she describes how the materiality of electronic equipment and the noises that can be produced with them form a delicate aesthetic praxis. In her video essay, Niina Oisalo brings forth questions of representations and connections made in audiovisual material through cuts, textures, and possibilities of “24 frames a second”. Meri Kytö, in turn, writes of electricity as an infrastructural necessity for sensing, something that is also produced by our bodies themselves. The last piece in this section, by Robert Willim, explores the mundane qualities of electrically extended realities using an electric guitar cord as a point of reference.

The thread consists of a rich and varied collection that not only draws the contours of sensory media anthropology, but also plays with various formats to engage the “reader”.

Under the theme steps, Mónica Degen explores how steps both frame and are understood as incremental movements and progress. She provocatively asks why those who travel more, such as refugees, are often considered to have lower social status than those who take fewer steps. Niamh Ní Bhroin explores how our steps have increasingly become captured as digital traces locking in our environment and experience and in turn becoming a source of information for commercial analysis.

Under the theme moved, Leonardo Custódio ponders on the differences a documentary makes. He provides the example of the emotional reactions to poverty in relation to the documentary Complexos. Marie Gorm Aabo writes about the practice of deep listening on the move – initiated by the experience of tinnitus – and presents a sound collage as a demonstration of this practice. Finally, Meri Kytö sends the reader to orbit and further to outer space and writes about the possibilities of instrumentally enhanced and instrumentally translated perception.

Under the theme gut feeling, Marie Gorm Aabo explores multisensorial impressions in visual pairings, and how her gut feeling drives her awareness of additional ways of sensing and experiencing sound. Mónica Degen explores how our intestines and brain are connected in ways that influence our decisions, mood, feelings, and overall well-being. The gut therefore needs to be recognized more explicitly as part of our knowledge production processes. Sanne Krogh Groth indicates how her gut feeling influenced her experience of a Jathilan event in Java. Initially, her gut responded comfortably to her recognition of the ritual. However, it also influenced her awareness of new, additional, and unsettling elements of her experience. She asks how we should recognize and trust our gut in different situations. Finally, Nanna Hauge Kristensen takes us on an open-ended microbial journey where her gut feeling, initially faintly but more persistently through different experiences, informs and influences her decision to visit Chile for research.

Under the theme walls, Aine Mangaoang introduces images of walls from her empirical research at prisons in Norway. The high walls surrounding the prison reinforce the physical boundaries between what is on the inside and on the outside, between freedom and imprisonment. Nina Grønlykke Mollerup’s contribution explores the significance of walls made to control the movement of people based on her research in Cairo. She argues that walls at once bind our senses while also potentially, at least at times, enable new imaginaries. Paying attention to history and provenance, Niamh Ní Bhroin examines how walls, initially established as boundaries around a farm, collapse and crumble with time, or serve as homes for cold-blooded animals and wildflowers, indicating how our human-centric sense and understanding of walls can evolve and take on different ecological significance with time.

Under the theme clocks, Leonardo Custodio’s piece highlights the various kinds of clocks he needs to respond to when engaging in academic research and activism, and how these clocks and their different momentum and rhythms influence his working structure and perception. Finally, Ieva Gudaityte focuses on the significance of radio as a marker of time in urban and rural settings and how it influences perceptions of different times of day and the significance of the differentiation between home and public life and affairs.

References

Alper, Meryl. 2018. “Inclusive Sensory Ethnography: Studying New Media and Neurodiversity in Everyday Life”. New Media & Society, 20 (10): 3560–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818755394.

Balcetis, Emily. 2023. “Why We See Things Differently | Emily Balcetis | TEDxCambridge”.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tu2rryXVXLY.

Classen, Constance. 1997. “Foundations for an Anthropology of the Senses”. International Social Science Journal 49 (153): 297-447

Degen, Mónica, and Gillian Rose. 2022. The New Urban Aesthetic. The New Urban Aesthetic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350070868.0006.

Drever, John L. and Andrew Hugill (eds.) 2023. Aural Diversity. London & New York: Routledge.

Herman, Amy E. 2016. Visual Intelligence – Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Hjarvard, Stig. 2013. The Mediatization of Society and Culture. New York: Routledge.

Hobart, Mark. 2010. “What Do We Mean by ‘Media Practices’?” In Theorising Media and Practice, edited by Birgit Bräuchler and John Postill, pp. 55-76. Oxford: Berghahn.

Howes, David. 2022. The Sensory Studies Manifesto: Tracking the Sensorial Revolution in the Arts and Human Sciences. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Järviluoma, Helmi and Leslie Murray (eds.) 2023.Sensory Transformations: Environments, Technologies, Sensobiographies. London and New York: Routledge.

Kahan, Dan M, David A Hoffman, and Donald Braman. 2009. “Whose Eyes Are You Going to Believe? Scott v. Harris and the Perils of Cognitive Illiberalism”. Harvard Law Review 122 (3): 837–906.

Kytö, Meri 2020. “The Senses and the City: Attention, Distraction and Media Technology in Urban Environments”. In The Routledge companion to urban media and communication, edited by Zlatan Krajina & Deborah Stevenson, pp. 371–78. London & New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315211633-39

Kytö, Meri. 2022. “Soundscapes of Code: Cochlear Implant as Soundscape Arranger”. In Aural Diversity, edited by John L. Drever and Andrew Hugill, pp. 73-81. London & New York: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781003183624-8

Mollerup, Nina Grønlykke. 2020. “‘What Violent Conflict Tells Us about Media and Place-Making (and Vice Versa) – Ethnographic Observations from a Revolutionary Uprising”. In Theorising Media and Conflict, edited by Philipp Budka and Birgit Bräuchler, pp. 181-195. Oxford: Berghahn.

Mollerup, Nina Grønlykke, and Sherief Gaber. 2015. “Making Media Public: On Revolutionary Street Screenings in Egypt”. International Journal of Communication 9: 2903–21.

Moores, Shaun. 2017. Digital Orientations. Non-media-centric Media Studies and Non-representational Theories of Practice. New York: Peter Lang.

Pink, Sarah. 2010. “The Future of Sensory Anthropology/the Anthropology of the Senses”. Social Anthropology 18 (3): 331–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00119_1.x.

———. 2011. “Sensory Digital Photography: Re-Thinking ‘Moving’ and the Image”. Visual Studies 26 (1): 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2011.548484.

———. 2015a. Doing sensory ethnography. London: Sage;

———. 2015b. “Approaching Media through the Senses: Between Experience and Representation”. Media International Australia 154 (1): 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1515400103.

Pink, Sarah, and Kerstin Leder Mackley. 2013. “Saturated and Situated: Expanding the Meaning of Media in the Routines of Everyday Life”. Media, Culture & Society 35 (6): 677–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443713491298.

Pertierra, Anna Cristina. 2018. Media Anthropology for the Digital Age. Cambridge: Polity.

Postill, John, and Mark Allen Peterson. 2009. “What is the Point of Media Anthropology?” Social Anthropology 17 (3): 334–44.

Salter, Chris. 2018. “Disturbance, Translation, Enculturation: Necessary Research in New Media, Technology, and the Senses”. Visual Anthropology Review 34 (1): 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12156.

Vermaas, Pieter E. and Philosophy Documentation Center. 2010. “Philosophy of Engineering and Technology: A New Book Series”. Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology 14 (1): 55–59. https://doi.org/10.5840/techne20101418.