Where does the history of human rights begin: centuries, even millennia earlier, or a mere few decades ago? What constitutes this history and what can we really learn from ‘the textbook narrative’ – the unilinear, forward-looking tale of progress and inevitable triumph of human rights authored primarily by Western philosophers, politicians and activists, and reproduced also in books of international law? Does such a distinguishable entity as ‘the history of human rights’ even exist, or are efforts to read evidence in past events of the later ‘evolution’ of human rights mere ideology?

These questions were originally motivated by our early encounters with the dominant historiography of (human) rights. As we studied this scholarship we found ourselves growing confused. If our engagement with critical legal scholars had taught us anything, it was about the complexity of indeterminate (legal) rights claims, the various dark sides accompanying human rights action, and the very concept of human rights.

Consequently, whether we approached human rights as open-ended and free floating signifiers in everyday use, or as contested meanings in philosophical, ethical and religious debates, we lacked certainty over what human rights ultimately meant.

In regards to historiography, our problem was the reverse. As we discovered the influential body of law books, which, commonly in their first pages, recounted the history of human rights, we were struck by a sense of internal coherence, logical continuity and seeming comprehensiveness instead of the contradictions, conceptual fuzziness and competition of perspectives characterizing most scholarly work.

Where we expected to encounter passionate disagreement, we found fluent prose freed of references – evidently, we were dealing with a tale holding the status of uncontested common knowledge that, in conformity with established customs of academic writing, needed no backing from footnotes.

Our exploration awakened a sneaking suspicion that we were – with only slight variation of highlighted social theorists or events – effectively reading the same ‘textbook narrative’ over and over again, as if it had been simply copied and pasted from one book to the next.

We were amazed at how this narrative in its consistency contrasted not only with general conventions of academic writing but with the content of other law textbooks. Given incessant legislative modifications, treaty interpretations and court decisions, such legal texts face constant updating, resulting in some of the shortest scholarly ‘expiration dates’ in higher education. Consequently organizing a course on, say, competition law or general international law would be unthinkable with a textbook containing sections several decades old.

Not so with human rights, we discovered, leading us to conclude that up until this moment, generations of aspiring human rights lawyers had been trained into thinking that the history of human rights forms a completed, ‘cold’ field of inquiry with ‘nothing left to study’.

Imagined Antiquity and the ‘Big Bang Theory’

Soon we noticed that the textbook narrative entailed two distinct variations, which, despite seeming incompatible, ultimately convey the same message. The first variation – one that we call ‘the Tale of Imagined Antiquity’ – directs its explanatory focus on historical events, departing commonly with the Stoics of ancient Greece and the policy makers of the Roman Empire.

As this variation moves through time, it connects dispersed historical events and eras into a neat chronology, highlighting the occasional benevolent policy initiated by isolated rulers in medieval times – even if this era is commonly considered as the ‘dark ages’ of rights – and connects human rights thinking to natural rights as articulated, among others, by Francisco de Vitoria, Hugo Grotius, Emer de Vattel and John Locke, sometimes Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Immanuel Kant.

This variation views the Enlightenment as the most significant ‘moment of birth’ for human rights, emphasizing the importance of the French and American Revolutions and the two Declarations that they inspired, namely the US Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the Bill of Rights of 1791, and their French counterpart, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des droits de l´homme et du citoyen) of 1789.

Aided further by the rise of capitalism, modern technology and modernity, so this variation continues, human rights notions continued their spread through different social movements, and finally received their logical culmination in the adoption of the UDHR in 1948.

By contrast the second version – what we call ‘the Big Bang Theory’ – effectively downplays the importance of developments from past centuries, celebrating instead the adoption of the UDHR as the foundational moment for the contemporary human rights phenomenon.

This variation emphasizes a vacuum of rights initiatives in the inter-war period, and highlights global abhorrence awakened by the Holocaust as the decisive factor behind the newly sprung universal consciousness of mankind. This in turn resulted in worldwide mobilization to ensure that similar atrocities would never occur again – so this variation continues – thus laying the foundations for the rapid geographic spread and empirical growth of the post-UDHR contemporary human rights phenomenon, eventually elevating human rights into the ‘idea of our time’.

Despite their differences, ultimately both of these versions convey the same message: they tell a hagiographic tale, a ‘Whig narrative’ of the past as unilinear progress and global improvement in which humanity is on a steady march away from superstition, cultural fanaticism and irrationality towards secularization, rationality and modernity.

Jointly this results in the ultimate triumph of ‘good’ over ‘evil’, and the eventual dawn of the ‘age of rights’. From a methodological perspective, our description of the textbook narrative raises several observations. First, the collective oversight of what it addresses – the history of a movement, a discourse, an ideology – as well as the broad-sweeping tendency to embrace isolated historical events exemplify implicit anachronism; the temptation to approach history writing from the context of contemporary concerns.

However, this ignores what these scholars take as historical ‘facts’ or as expressions of human rights thinking in eras before ‘rights talk’. Thus, whereas its details may be elaborate and extensively researched, the narrative neither problematizes the practice of history writing as such, nor situates its writers – the ‘authorial “I”’ – in the text by exploring her purposes, methodological assumptions or prejudices.

The textbook narrative ignores discussions of how reality is always mediated through language, thus resonating with ‘hermeneutic naïveté, the belief in immaculate perception’.

Consequently a reader is left wanting a thorough exploration of how one can talk of ‘knowing’ and ‘knowledge’, including historical knowledge, as well as how something like human rights can be argued to ‘exist’ in eras where the very concept of human rights had yet not appeared.

Such propositions have widespread resonance in many human rights writings that characterize human rights as providing ‘values for a godless age’. Also activist human rights scholars may refer to human rights as ‘sacred’, as Michael Perry famously did. Becoming aware of this crossing over into the realm of belief helps us to understand why we have witnessed such a strong textbook narrative on the history of human rights, and also clarifies the mechanisms through which this tale has acquired its predominant position.

Here we see repetition as central: the narrative’s uncontested status as ‘the truth’ appears to rest on endless repetition by scholar after scholar in book after book until everyone has effectively ceased to question its validity or accuracy, instead accommodating themselves to the narrative’s parameters.

As we have paired this finding with our observations that the textbook narrative is a story with unknown origins and authorship that is frequently presented without references, yet with virtually unaltered details, we see it as starting to resemble a myth.

By conceptualizing the textbook narrative as myth we capture its function as a potent legitimating strategy. Elisabeth A. Clark notes how narratives serve to ‘impose coherence, continuity, and closure on the messiness of life and of the historian’s sources; the historian then smoothes over the gaps and absences to create an “effect of the real”’.

These findings apply to the textbook narrative which ‘creates an effect of the real’ by contributing to a global sense of belonging to a community. Simultaneously it inspires action that ends up confirming the narrative, thereby naturalizing the influence of the contemporary human rights phenomenon. Thus the textbook narrative ‘is not a “neutral” form into which content is stuffed, but rather, it is ideologically freighted’.

It conceals the fact that the naturalization of human rights is an important exercise of power, and instead of merely offering information about the history of human rights, acquires elements of persuasion and indoctrination on how the history of human rights should be considered.

Whereas prior to the new millennium the entire field barely existed as a distinct subfield of historical scholarship, in recent years human rights have become one of the fastest growing areas of research in political and legal history and intellectual history. Keen focus over the past decade on human rights characterizes also the fields of anthropology, philosophy and theology – a joint engagement, to use Mark Goodale’s terminology of this trajectory within anthropology, that reflects the position of human rights as the ‘idea of our time’, of their position as ‘doxa’.

However, whereas this recent engagement comes forth as a scholarly shift from ‘the old to the new’ among historians, it entails unsuspected commonalities. First, often implicitly many recent treatises by historians have accommodated themselves to the narrative’s parameters, finding evidence either in support of or against human rights claims primarily in the thematic and temporal eras of their expertise.

From this perspective this recent engagement has in part strengthened rather than challenged the narrative’s dominance. Second, despite making the opposite argument about historical continuity, surprising similarity connects the textbook narrative and the revisionist camp, namely the assumption of human rights as characterized by an ‘essential’ significance.

We assign this view to the heart of arguments that, for example, the rights of man of the early nineteenth century were not human rights claims because their intent was in guaranteeing the rights of citizens within the institution of the state, not challenging the state’s very sovereignty via forwarding these claims to an imagined ‘humanity’ – a view that is thus depicted as capturing the ‘genuine’ essence of human rights.

As has already been noted, we do not embrace this approach that to us signals the kind of conceptual rigidity that makes no sense in light of our three decades of human rights research. Indeed, the history of the contemporary human rights phenomenon has never been organized around a distinct, absolute and unchanged conception.

As we have examined human rights practices, uses of the discourse, communities, artefacts, ideas and values in the present day, only one conclusion has both become and remained a fact: it is impossible to offer simplistic definitions of what human rights are. They appear simultaneously as ‘absolute and undefined’, existing both as empirically observable external ‘things’ in the world and as intrinsic and unobservable ideas in the minds of people.

We maintain that conceptual vagueness is an integral element in the global popularity of human rights: only by being continually open-ended, yet seemingly absolute, can human rights continue to capture the imaginations of people around the world.

Thus analyses of the human rights discourse should become ever more conceptually self-conscious and ever more aware of the difficulty of grasping the experience of others in terms adequate to its reality. We propose an approach that is premised on a nuanced and multifaceted conception of its target of investigation, having as its anchor consistently the contours of the textbook narrative. In addition, we focus partly on the discourse of human rights, but without restricting our gaze on its etymology.

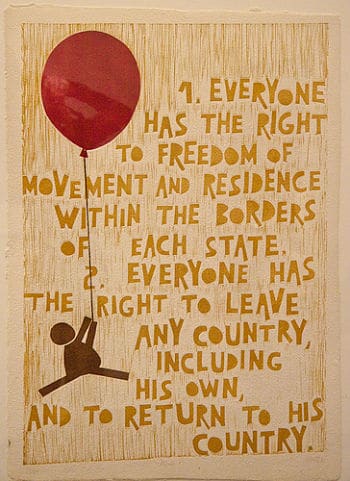

We focus particularly on the structural features accompanying rights claims as we identify them today, both in a moral sense and also a legal sense. Here the first element focuses on the concept of the human as an autonomous individual, and traces down processes through which we come to witness the eventual emergence of the universalizing category of everyone; a category that is far more expansive than most historical alternatives.

In particular we explore how and when this conception has emerged as defining the border of humanity, a process to which we connect distinct humanitarian considerations and emotions.

Thus one part of our inquiry touches also on how such sentiments have emerged and been expressed, this outcome resulting in a particular kind of contribution to the history of this ideal. The second element of relevance is an emphasis on entitlements rather than duties. The third is that (human) rights address relationships, either the individual’s relationship to oneself over the notion of self-dominium, to others, to states, or vis-à-vis the international community.

Fourth, is that (human) rights address these relationships, principally either through attempts at dynamic change, or maintaining the status quo. Finally, human rights embody certain values, of which for us the most important are historically the notion of freedom and the equal worth of all. In the following section we connect these abstract statements to the chapters of this volume to elaborate their meaning.

We propose that the next phases in the study of the history of human rights should focus on chasing out the multifaceted, co-existing and conflicting meanings that diverse moral and political imaginations build on.

We introduce a fresh mapping of relevant avenues for further inquiry, the analysis of which we hope will proceed toward shared conceptual diversity that allows us to collectively start seeing beyond the seeming self-evidentiality offered by the textbook narrative of origins. We hope tot see both renewed as well as more sustained collective ‘reengagement’ with the theme, thus slowly accompanying us further down the path of genuinely greater understanding over this fascinating amorphous phenomenon and idea ‘of our time’ – both in history and today.

******************

This post builds on our introduction for Revisiting the Origins of Human Rights, reproduced here with the kind permission of the Cambridge University Press.

Check out our book blog: Revisiting the Origins of Human Rights