In the depths of the Depression, two girls were born to Jewish parents in New York City. One, in 1933, was Ruth Bader, later Mrs. Ginsburg. The other, a year later, was me. The U.S. Census classified us as Hebrew Race. Ivy League colleges limited Jews to 15% of admitted students. Hotels could refuse accommodations to persons with “Jewish names” or who looked Jewish. Landlords and real estate agents denied Jewish clients; towns had restrictive clauses excluding Jews. My mother, Lena Rosenstock, interviewing for a teacher position in Bronxville, a New York suburb, was told that Jews were not hired. A group of summer cottages built for Jews on a lake near Milwaukee was burned to keep them out.

Ruth Bader and I just escaped the colleges’ Jewish quota, quietly removed in 1951. We didn’t escape the postwar pressure on girls to marry young and bear children. In 1957-58, we both were married, mothers of babies, enrolled in graduate programs at Harvard along with our husbands. We each were among less than a dozen women students in our graduate cohort, for her starkly few among several hundred men, for me not so stark because the Anthropology program was much smaller. She transferred to Columbia when her husband obtained a job with a New York law firm. More than fifty years later, Ginsburg remembered the unexpected helpfulness of fellow students in Harvard Law. I recall my cohort of women at Peabody (Anthropology was housed in that building), we were close friends in the face of dominating patriarchy. One of the women, incidentally, was African-American. None of us women in that cohort was mentored or given opportunities; we were spared professors’ promises of career assistance in exchange for sex, since women would not have careers. We were beneficiaries of “benign neglect”.

We were beneficiaries of “benign neglect”.

Our paths diverged, Mrs. Ginsburg and Mrs. Kehoe, hers to change the world for everyone discriminated against on the basis of sex. For me, anthropology opened opportunities to work against Manifest Destiny ideology. I was able to change textbooks on North American Indians (as Native Americans were then called) to ethnohistory instead of vignettes from classic 19th-century ethnographies (Kehoe 1981). In the 1970s, counterculture romanticism made American Indians popular, creating a market for textbooks on them. A publisher’s rep told her editor that I taught the course at Marquette University, he phoned asking me to write a textbook for them. With my first sabbatical coming up and no possibility of traveling for research, three young boys at home, I agreed, provided I could write it differently from its competitors. Four manuscript reviewers who taught the course in their universities recommended rejection, saying they taught cultures, not history. The editor took a gamble (his words). North American Indians: A Comprehensive Account opens with Paleoamericans coming into the country 15,000 years ago, continuing in each culture-area chapter seamlessly to the present. The book sold well (in its limited market) and since it appeared, newer texts on American First Nations have used its ethnohistorical model.

Law, in the hands of a brilliant, very hardworking person, can substantially change the lives of millions of Americans. Anthropology seems small potatoes in comparison. But small potatoes are nourishing––when I was working in a village near Lake Titicaca, small potatoes were what we ate, day in and day out. The project, directed by my former undergrad student Alan Kolata (University of Chicago), rebuilt what Kolata, and Clark Erickson across the Lake, interpreted were raised fields that would have fed the Tiwanaku state. After a very successful trial, the next year, 1988, Kolata expected the villagers to continue rebuilding and planting the ridged fields, but they were reluctant to do so without wages. Seed potatoes, shovels and pick-mattocks were not enough, they said, they needed money. The project was a spin-off from Kolata’s excavations at Tiwanaku, its only funding a small grant. I volunteered to live in one of the villages and try to learn why bounteous harvests of potatoes were not enough incentive. As I chopped up the clods on the ridges along with the other women, I learned of the desperation of these Aymara farmers for money, explained that Doctor Alan did not have cash, and near the end of the planting season, the villagers agreed to put in his seed potatoes. Now comes the real-world part of the story: the Bolivian government was told of the promise of rehabbing ancient fields and made it a national project, introducing ridge-and-ditch agriculture all over the country. The system was designed for the marshy borders of Lake Titicaca and failed in other environments. State politics screwed up an anthropological endeavor to do good.

Anthropology is a humanist science. Unlike mainstream History, it doesn’t Make America Great (Kehoe 1990), unlike Psychology, it doesn’t generalize about individuals, in the framework of possessive individualism. Unlike Sociology and Political Science, it doesn’t rely on quantifiable surveys. Few students take our courses, compared to the numbers in those American-culture fields. (Silver lining is that those few are often remarkably bright and thoughtful.) American politics militate against us. The National Science Foundation was developed by men who had worked at Los Alamos on the Manhattan Project; their mission to keep America militarily strong shaped its policies and version of science (Reisch 2005, Solovey 2013, 2020). Anthropology did contribute substantially to many beneficial programs (Kehoe and Doughty 2012), without changing most Americans’ notion that anthropologists wear pith helmets.

Get Up! Stand Up! Don’t Give Up the Fight! shout yard signs in my pleasant middle-class White neighborhood in the country’s most segregated city, Milwaukee. As an anthropologist, it bothers me that it’s three imperatives. Not “We Must Get Up!”, but orders: Get Up! You! Echoes of the slaves’ overseer’s commands. In my neighbors’ manicured lawns maintained with petrochemicals, it’s the tiniest evidence of Americans’ deafness to the nuances we anthropologists treasure. The signs make me think, yes, we as anthropologists do get up and go to a huge and rich variety of communities; we do stand up to tell the worth of all humankind, and of its diversity. Many do not give up struggling for social justice. We saw, for eight years, how one anthropologist’s teachings formed a President, her son, who didn’t give up the fight. We have seen the horrifying backlash.

From Franz Boas’ decades of traveling to Black colleges to fight with them for opportunities, of his nurturing of not only Zora Hurston but also of other Black anthropologists such as William S. Willis, Jr., and his consistent support of W. E. B. DuBois, that anthropologists were standing up for Black Lives Matter. Boas also nurtured Ella Deloria, Lakota, and Archie Phinney, Niimipuu, and worked collaboratively with a number of Northwest Coast First Nations leaders. Among the first generation of Boas’s students were Frank Speck, who steadfastly worked with remnant First Nations in the East, and Alanson Skinner who partnered with Amos Oneroad, a Dakota, to record histories and material and intellectual cultures of Midwestern and Eastern First Nations, and, yes, Alfred Kroeber who may not have seemed “woke” but worked to build encyclopedic descriptions of California nations. Sol Tax’s Action Anthropology presaged today’s calls to listen to disadvantaged communities and follow their voiced needs, humbly (Stapp 2012). Anthropology has never had the numbers nor the political ties to wield power. It’s foolish to suppose that will change. We can stand up, witness, and assist as we can in the struggles to preserve our planet and ameliorate the living conditions of the less fortunate within our species.

We can stand up, witness, and assist as we can in the struggles to preserve our planet and ameliorate the living conditions of the less fortunate within our species.

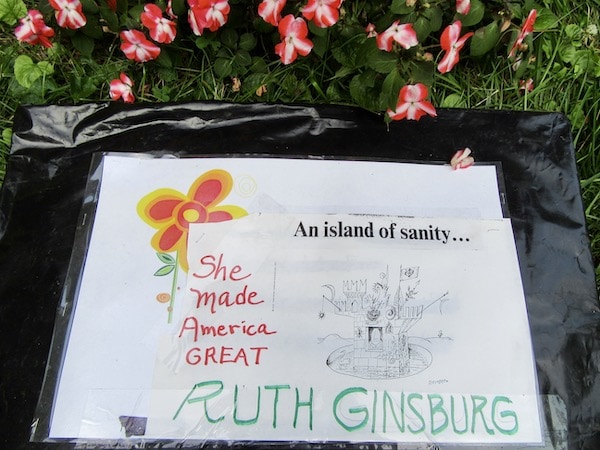

Was Mrs. Ginsburg one of the other mothers in the little park at the foot of Divinity Avenue, sitting beside their babies in the prams borrowed from the Harvard Wives Club? Reading textbooks as our babies slept? I shall never know. All I need to know is that America is great because one of those young mothers earned a J.D. and persisted in her quest for justice to all. I have been a worker bee, with my fellow anthropologists flying around to gather minuscule bits that put together, may nourish all of us. The good we’ve done is small, but real. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a lodestar shining over us. Risen, I’m thinking, from that circle of young parents at Divinity Avenue.

References

Kehoe, Alice Beck. 1981. (Revised editions 1992, 2006) North American Indians: A Comprehensive Account. Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kehoe, Alice Beck. 1990. “‘In Fourteen Hundred and Ninety-two, Columbus Sailed…’: The Primacy of the National Myth in American Schools.” In The Excluded Past, edited by Peter Stone and Robert MacKenzie, 201-215. London: Unwin Hyman.

Kehoe, Alice Beck, and Paul L. Doughty, eds. 2012. Expanding Anthropology, 1945-1980: A Generation Reflects. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Reisch, George A. 2005 How the Cold War Transformed Philosophy of Science. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Solovey, Mark. 2013 Shaky Foundations: the Politics-Patronage-Social Science Nexus in Cold War America. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Solovey, Mark. 2020, Social Science for What? Battles over Public Funding for the “Other Sciences” at the National Science Foundation. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Stapp, Darby C., ed. 2012. Action Anthropology and Sol Tax in 2012: The Final Word? Memoir No. 8, Journal of Northwest Anthropology. Richland WA: Northwest Anthropology.

Featured image by angela n. (Flickr, CC BY 2.0).

Alice, thank you for this essay/memoir. It’s sad to realize how many millions of people in this nation (judging by the current presidential election results) have learned nothing (or rejected what they learned) from anthropologists like you and legal scholars like RBG. But millions more have, and we thank you.

Warm regards,

Bonnie

Excellent, Alice. Thanks, Marjorie

Great history of scholars who follow the bees in the blooming work of new generations. We keep on rowing our little canoes. Thanks for the text Barbara Arisi