Working the System is a great book. It holds the promise of its subtitle and offers a deep ‘political ethnography of the new Angola’. Through rich ethnographic snippets infused with empathy to the people whom the book is about, Schubert builds a strong analysis of ‘the reciprocity and consociality of the power relations’ that have shaped society in Luanda since the end of the war (p. 5). But Working the System also speaks beyond the specificities of ‘the new Angola’. It develops subtle ideas about the (un)making of race and social classes, the workings of collective memory and personal aspiration, and the double script of familiarity and estrangement behind the construction of political subjectivities.

As a scholar working on Angola myself, I can only welcome Schubert’s precious ethnography about such as particular place (the capital city of Luanda) at such a specific time, between the end of the civil war in 2002 and the political turn of December 2016, when President dos Santos announced he would not run up for the 2017 elections, after 38 years in power. Moving away from the flat picture of an ‘oil-rich, neo-authoritarian state’ where press freedom is restricted, elections rigged and privileges of incumbency abused, Schubert introduces us to dozens of people — some anonymised ordinary citizens, others public speaking on the record.

All are portrayed in such a vivid and empathetic way that we close the book with the feeling we somehow know them personally.

We meet Senhor Adriano, the nostalgic veteran deeply rooted in his neighbourhood; with him, we come to regret the past glory of the MPLA (the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), yesterday’s vanguard liberation movement, today the entrenched party-state. As we sit for a beer with Simão, we share the dreams and struggles of this young entrepreneur whose world is divided between Luanda, Paris and Brussels. We contemplate the city through the disillusioned eyes of Dona Mariana, a witty sexagenarian who is tuned in to the latest gossip on social media. Leandro shares with us his aspirations to a ‘good life’: branded clothes, big cars and fancy parties in Luanda’s famously overpriced nightclubs.

Schubert is definitely a good story-teller. But his writing skillfully keeps the balance between the sensitivity of an account at the first person and the reflexivity of an analysis in dialogue with a wide range of scholars. The result is that every encounter sounds both intimate and purposeful. The text effectively ‘decenter[s] and delocalize[s] the anthropological gaze [by moving] between different social strata and locales, not only imitating [the author’s] own movement as a researcher across spatial and social divides but also attempting to connect seemingly disparate realities that are in fact intimately connected’ (p. 22). Because Schubert never takes for granted what is, or what is not, political, he manages to unravel the very concrete ways by which hegemony is coproduced ‘beyond the cultivation of consent by the dominant’ (pp. 2-3).

Schubert is definitely a good story-teller. But his writing skillfully keeps the balance between the sensitivity of an account at the first person and the reflexivity of an analysis in dialogue with a wide range of scholars. The result is that every encounter sounds both intimate and purposeful. The text effectively ‘decenter[s] and delocalize[s] the anthropological gaze [by moving] between different social strata and locales, not only imitating [the author’s] own movement as a researcher across spatial and social divides but also attempting to connect seemingly disparate realities that are in fact intimately connected’ (p. 22). Because Schubert never takes for granted what is, or what is not, political, he manages to unravel the very concrete ways by which hegemony is coproduced ‘beyond the cultivation of consent by the dominant’ (pp. 2-3).

In chapters 1 and 2, Schubert shows how a hegemonic system relies on a double process of embedding and territorialising memory. Chapter 1 offers a critical reading of the official history built by the ruling party. Against the picture of a straight trajectory leading from a long liberation struggle in the 1960s and 1970s to the booming decade fed by petrodollars of 2002-2012, Schubert exposes the mechanisms of ‘an amnesiac master narrative’ that allows the MPLA to ‘equate peace with infrastructure reconstruction’ and to dodge any talks about ‘substantial reconciliation’ (pp. 51-52). However, this distorted narrative also prevents the ruling party from instrumentalising national history. It actually opens possibilities for contestation elaborated throughout the rest of the book.

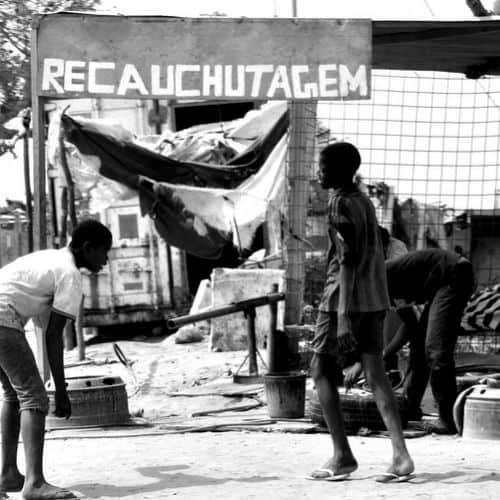

In order to illustrate how memory politics infuse daily life in Luanda, chapter 2 introduces us to a series of landmarks in a neighbourhood known as the cradle of the liberation struggle. As we listen to the memories of local residents, old and young, we get a sense of the place. Schubert takes inspiration from Navaro-Yashin’s ‘affective geographies’ to bring to life the unresolved tensions that animate the relationship between historical events, official discourses and counter-memories. My only regret here is the lack of photographic record and the relative weakness of the map sketches.

The following three chapters open up the discussion to broader conceptual discussions that are relevant to anyone in political anthropology. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 discuss how dynamics of entitlement and subjection are negotiated on a daily basis through abstract concepts (“race”, “class”, “patronage”, “good life”) and concrete practices (how people address one another, how money circulates, how critiques are being verbalised – or not).

Chapter 3 explores the complex classism that plays out in Luanda. It describes a urban society marked by racial stratification, where decades of colonialism have put whites and mestiços at the top; and structured around a narrow nationalist narrative that distinguishes the role of the vanguard from the homogenized adhesion of the masses. In 30 pages, Schubert accomplishes a veritable academic ‘tour de force’. Not only does he deconstruct the interplay of race and class in the formation of Angolan elites – a topic that is still largely taboo in Angola nowadays; but he convincingly argues that this interplay – and the fact that it isn’t settled on any clear definition of angolanidade (‘angolanness’)— actually allows both the MPLA leadership and its opponents to mobilise discourses of ‘authenticity’ without ever stabilising them into a rhetoric of autochthony for political gains.

Chapter 4 develops further this double-edged relationship to ‘tradition’ in Luanda through the question of kinship, both real and symbolic. Responding to a central trope in African political studies, i.e. patronage and corruption, Schubert unravels how family links are mobilized for personal advancement – a classic system of clientelism known as cunhas in Angola. He bravely sews together public stories of influence peddling with his own encounters with various administrations, in order to describe how familiarity and hierarchy are defined and negotiated in relation to each other.

Some anecdotes are exhilarating – such as this young employee at a cellphone shop left totally puzzled by the fact one of her patrons decided to call her ‘mum’ in order to show respect.

But besides the many jokes that circulate in Luanda about these connections and their sometimes haphazard mobilisations in everyday life, the reality of ‘naming practices and naming taboos’ constitutes ‘an ambivalent resource’ (p. 136) that can backfire on those who are unable to activate the right cunha in the right situation. Here, I expected Schubert to push his analysis further. I’d argue that cunhas are not always ambivalent. People are often forced to mobilise a personal connection –not because they need to achieve a specific outcome but because they will literally lose family and friends for not doing so. Moreover, daily life in Luanda is not only a matter of activating a cunha but also of being oneself mobilised by/for a relative. Once forced to ‘lend’ their symbolic capital to a ‘relative’, anyone can find herself caught in a web of reciprocity that implies not only the ‘borrower’ but the network of this person. In many instances, cunhas are impossible to escape.

Chapter 5 tackles what is probably the best-known aspect of Luanda nowadays: the confounding high cost of daily life. Elites unabashedly show off their luxury shopping while international reports point to repeated human rights abuses across the country. The contradictions of a ‘magnificent and beggar land’ are well known (Soares de Oliveira, 2015) but Schubert is one of the first scholars to seriously ask what these contradictions do to the way citizens project themselves into the New Angola. Beyond listing easy money making schemes or ostentatious behaviours, Schubert describes what he calls a ‘culture of immediatism’ where ‘ideas of a better life are not just limited to overnight wealth and flashy cars but also include desires for the state, its services, and a normal life, cultivating the consent of large parts of the citizenship.’ (p. 157) What is missing in this account, however, is the highly gendered bias that affects this new imaginary of citizenship and entitlement. The three main protagonists in this chapter are Leandro, Simão and Zeca, three young men. Schubert notes that to all of them, the culture of immediatism implies sacrifices and romantic relationships seem to be first on the list: ‘here, the women only want your money’, says Leandro (p. 148). Hearing what a few young women could say about their relationships with these young entrepreneurs would have probably given more weight to the idea of a collusion between love and business interests, either by offering an alternative vision of romance or by providing explanations about why ‘money’ is so crucial to young women…

If we put the gender bias aside, Schubert insightfully points towards the disruptive potential of immediatism.

All his respondents express a certain ‘moral unease’ when they admit that their wealth is directly conditioned by their complicity with the corrupt party-state. To Schubert, these ultimate ‘moral reservations’ indicate that the hegemony of the ruling party is constantly renegotiated on the ground; they also ‘open up a terrain of political contestation’, explored in the last sections of the book (p. 157).

Chapter 6 indeed focuses on the open calls for protest that multiplied in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. The chapter focuses on the run-up to the general elections of September 2012 and astutely brings back together the manyfold political repertoires detailed in the previous chapters. We thus see how a handful of young activists unravel the dominant historical narrative imposed by the MPLA and how a collective effort of citizen’s scrutiny exposes the myth of unhindered growth in the post-war era. However, because chapter 6 closes on the crushing victory of the MPLA at the polls in 2012, the general conclusion doesn’t brim with optimism. Schubert rather closes the book on the ‘very ambivalent political subjectivities’ (p. 185) at work within the system. ‘People creatively use the elements of the system to work it’, summarises Schubert, before carefully hypothesising that these ‘inventions of the everyday’ somehow express ‘alternative political visions of what Angola is, or could be’ (ibid.).

With the distance we have today, such a conclusion fails to address the wave of change that has been rolling over Luanda since the election of dos Santos’ successor in August 2017 (after the book went to print). Against all expectations, President João Lourenço boldly attacked the oligarchy by dismissing about three hundred high-ranking public functionaries, including the sons and daughters of his predecessor. We are now inclined to think that the strongest ‘disruption’ that triggered change in Angola eventually came less from the work of a handful of activists in 2011-2012, than from the brutal economic crisis of late 2014. The epilogue is thus a very welcome addition to the book. Indeed, if in 2012, the possibility of open resistance to the regime remained ‘very ambivalent’, five years later, the ‘culture of immediatism’ described in chapter 5 has definitely reached its limits seriously crippling the hegemonic machinery.

So if in the detail, one could argue that Schubert’s analysis of Angola’s opposition repertoires somehow fell short of current civil society developments, the broader argument of Working the System remains valid: ‘even explicitly oppositional political action has to tap into the repertoires of dominant ideology to be effective’ (p. 159). As a matter of fact, the capacity of this book to absorb the shock of fast-paced political transformation in Angola is certainly the best proof that it is worth not only being read but being read again!

Work cited

SOARES DE OLIVEIRA, Ricardo, 2015, Magnificent and Beggar Land. Angola since the civil war, London: Hurst and Co Publishers.

Featured image (cropped) by gabriel.macedo (flickr.com, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Jon Schubert. 2017. Working the System: A Political Ethnography of the New Angola. Cornell University Press.