“It was so special” appears in simple white letters on a black screen while the performer Yadgar Bakir is speaking in a calm voice about childhood events that were once captured on images but are now irrecoverably lost. The audience is sitting on the floor of a rundown praying room inside a mosque of one of Rom`s poorest neighborhoods. There are the local imam, teenage boys who seem to know the place rather well and hipsters who are enjoying the unfamiliar place for an hour. The water basins, placed at the entrance of the room, rhythmically drip during Yadgar’s performance.

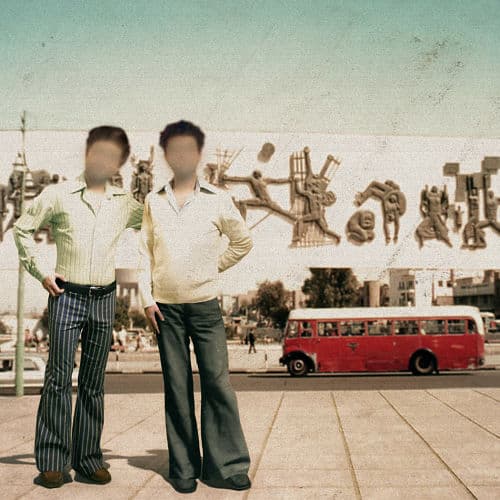

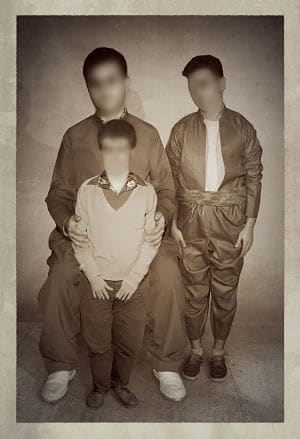

“White Faces. Reframing memory” (by Yadgar Bakir, directing: Linda Dorigo) is part of Rom’s Passeggiate Fotografiche Romane (Roman Photographic Walks). The event proposes multiple walks through Rome, following images exhibited outside on the street but also inside little vegetable corner shops and galleries. Yet Yadgar does not present many images. His performance rather addresses the opposite: the loss of family photographs through war and flight. He was a child during the “Al-Anfal” operation led by Saddam Hussein in the eighties, during which the former dictator of Iraq aimed to exterminate the ethnic minorities in the north of the country. Yadgar still remembers the army breaking into houses in search of traces that proved ties between the Kurdish civilians and the Peshmerga rebels.

Years later during his contemporary art study at Coventry University, UK Yadgar found a portrait of himself at the age of four years old, the only one remaining, torn apart into two pieces, one of them missing. Yadgar starts his performance with the projection of this one remaining image. The picture immediately captivates the audience. It evokes a narrative power as Chris Marker’s famous opening in Sans Soleil did by triggering the audience’s imagination through glimpses of one picture that was eternally imprinted in his memory. Yadgar continues by sharing his story through his own language, intercut with English phrases, a fragmented projection in Italian and the recreation of portrays staged with the participation of the audience. He takes us to many places: to an olive tree landscape and a family gathering around hot tea, to carefree childhood years and the tragic loss of friends and relatives. He does all this through words mostly spoken in Kurdish that I, and I suppose most of the people in the audience, do not understand. But the beauty of the performance lies exactly in this ability to create a shared language of emotion that breaks linguistic and cultural barriers.

While understanding nothing, everything is understood.

The combination of words, images and sounds provides a space to project one’s own memories of loss, to wonder about other places and other people who experience similar hardship. The performance creates a shared place where people are with others in human togetherness, if only for one hour.

At the end of the performance, Yadgar explains the story behind the one remaining image. It was his mother, like many other mothers, that had cut away the second half in order to avoid trouble. The picture showed a Kalashnikov of a Peshmerga in the background. The performance, Yadgar explains further, has a therapeutic effect that helps him work out and remodel his path. This creation of art as self-therapy of course can be a dangerous path. Too often it leads to what the anthropologist Ghassan Hage has formulated as “drowning oneself in a sea of self-reflexivity” (2009: 62) where healing writes out the actual subject of the story. But “White Faces. Reframing memory” does something else.

Rather than drowning in the dark sea of self-victimization, it illuminates the existential importance of storytelling as a crucial human strategy for sustaining a sense of agency in the context of disempowering circumstances.

In his work on storytelling and violence Michael Jackson writes: “stories enable us to regain some purchase over the events that confound us, humble us, and leave us helpless, salvaging a sense that we have some say in the way our lives unfold. In telling a story we renew our faith that the world is within our grasp.” (Jackson 2002: 17)

Locked inside my four walls while writing my PhD dissertation in Anthropology I have asked myself many times how to successfully use storytelling to convey what cannot be conveyed in standard academic texts. I needed to leave my writing desk and see “White Faces. Reframing Memory” to find some of the answers. It made me experience what has been described by Walter Benjamin as the stories’ ability “to survive the moment” (1968: 90) in a world where we are much too often exposed to sheer information. It reminded me that Anthropology needs greater experimentation and that we need to put ourselves out there in the world to encounter what could move the discipline forward.

References:

Benjamin, Walter (1968). Illuminations. Essays and Reflections. Introduction by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books

Hage, Ghassan (2009). Hating Israel in the Field. On Ethnography and Political Emotions. Anthropological Theory 9, p. 59-79

Jackson, Michael (2002). The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression, and Intersubjectivity. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press

Lems, Annika/Moderbacher Christine (2016). On being stuck in the wrong life: Homelonging, Movement and the Pain of Existential immobility. In: Sabina Leoncini, Julia Schwarz, Andreas Hackl, Miriam Gutekunst (eds.). Im/mobilities and boundaries: an ethnographical approach. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, Columbia University Press, p. 113-128

Further Links:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/WhiteFacesPerformance/

Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/225379428

Marker, Chris (1983). Sans Soleil. First Minute online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LGDu7YOlVuE (20.12.2017)