Every American President has grappled with the place of “rights” in U.S. foreign policy. However, the rise to prominence of the idea of “human rights”, despite its current ubiquitous position in American foreign policy formulations, followed a non-linear, sometime contradictory, path. The two books under review analyse two key moments of the Cold War that had a determining effect on the rise to prominence of human rights in postwar American diplomacy.

Rowland Brucken, an associate professor of history at Norwich University (Vermont, United States) investigates in his latest book A Most Uncertain Crusade: The United States, the United Nations, and Human Rights, 1941-1953 the emergence and transformation of the idea of human rights in American governmental thinking during the Second World War and early Cold War years. Between 1941 and 1953, the subject of human rights expanded greatly to become a central element of the American vision of a postwar global order before falling into abeyance after the unveiling of the Universal Declarations of Human Rights in December 1948. During this period, the United States government played a catalytic, albeit ambivalent – or “uncertain” as the book’s title suggests – role in defining the contours of the new United Nations human rights system.

According to Brucken, American foreign policy officials mobilised the universal human rights project to galvanise and give purpose to U.S. foreign policy during the Second World War. However, U.S. government officials from that era never failed to prioritise domestic and global policy objectives at the expense of the universal human rights project. In Brucken’s view, this ambivalence contributed to unduly prolonging, for example, racial discrimination in the United States and to structurally weaken the United Nations human rights accountability system.

According to Brucken, American foreign policy officials mobilised the universal human rights project to galvanise and give purpose to U.S. foreign policy during the Second World War. However, U.S. government officials from that era never failed to prioritise domestic and global policy objectives at the expense of the universal human rights project. In Brucken’s view, this ambivalence contributed to unduly prolonging, for example, racial discrimination in the United States and to structurally weaken the United Nations human rights accountability system.

As a result, Brucken argues that the human rights project that emerged in the wake of the Second World War was deeply flawed and conservative in nature.

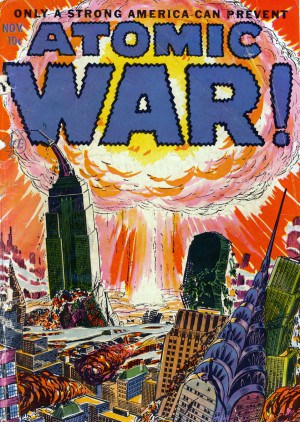

Central to this conservative turn is the role that American domestic politics and fear of communism played in U.S. human rights thinking. Local politics and constitutional strictures inhibited the federal government’s willingness and capacity to ratify binding international human rights covenants. Some of these constitutional technicalities were deeply rooted in Jim Crow laws and politics in the American South, where the southern states’ rights in the federal system were often invoked to deflect criticisms, domestic and international, of the treatment of African Americans and other racial minorities. Similar arguments were also invoked to prevent federally-sponsored legislative transformations. American non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also played an ambiguous role in this debate and other organisations, such as the American Bar Association, raised comparable federalist arguments due to fears that communist and totalitarian ideas might colonise American constitutional rights and liberties through United Nations channels. Reconciling domestic politics with a commitment to universalism was an unescapable predicament for U.S. government officials.

Brucken’s ambition with this book is not simply descriptive and historical. He seeks to unbolt three myths. Firstly, he convincingly debunks the myth of American human rights exceptionalism that suggests that only U.S. concepts of rights and liberties, a heritage from the European Enlightenment era, could – and still can – have a universal resonance. While this view appears to have been widely and genuinely held by many U.S. officials in the 1940s, Brucken demonstrates how this exceptionalism stemmed from a specific intellectual, political, and global context characterised by the rise to prominence of the U.S. during the Second World War and the emergence of Cold War anxieties in the United States.

Secondly, Brucken also sheds a crude light on the politics of human rights by showing how human rights advocacy was often trumped by sovereign claims.

This is a standard critique formulated by numerous past and current human rights advocates. However, contrary to Barbara Keys, Brucken’s conventional understanding of the relationship between human rights and sovereignty failed to fully grasp how U.S. government officials such as John Foster Dulles and Philip C. Jessup conceived of the idea of human rights not only as a weapon in the emerging Cold War ideological struggle, but also as a legitimacy enhancer for the United States government.

The third and final myth Brucken seeks to deconstruct is related to the role NGOs played in the drafting process of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. NGOs – both for and against the postwar human rights project – played an important role in mobilising resources and petitioning the U.S. government. However, Brucken tends to over-emphasise the determining effect that private individuals and organisations had on the drafting process. This type of argument tends to marginalise power politics in the drafting of universal human rights and, as a consequence, overemphasises the disinterested nature of NGOs and individuals in the process. While the historiography of U.S. foreign relations appears rather conservative in this regard, one should not fall prey to a celebratory history of human rights conceived of as a struggle often led by NGOs against sovereignty.

Despite these minor weaknesses, the book’s overall conclusion departs from standard narratives of this period. In the end, as Brucken argues, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a non-binding resolution of the United Nations General Assembly adopted on 10th December 1948, encapsulated almost 175 years of American jurisprudence. This was the first and probably the last major human rights success for American diplomacy. Indeed, due to growing Cold War tensions and conservative domestic politics, the U.S. human rights leadership deflated at the United Nations. The U.N. also suffered from this disengagement, and it took another 18 years before sovereign states agreed to ratify the International Covenants on civil and political rights and on economic, social and cultural rights. The United States, meanwhile, ratified the two human rights covenants only in June 1992 (only after having formulated several reservations).

Meticulously researched and crafted, Brucken’s book is dense and, at times, tedious to read. It lacks a strong and compelling overarching argument. He doesn’t squarely engage with the current historiographical debates about human rights, their genealogy, and their function in U.S. foreign policy. Another question that remains unanswered has to do with our understanding of that episode and its legacy: what place and role should the 1941-1953 episode occupy in the emerging human rights historiography? Was it a moment of rupture or continuity? How does it connect with the rise of human rights under the Presidency of Jimmy Carter? Are these two moments connected in some way?

According to Barbara J. Keys, a senior lecturer in American and international history at the University of Melbourne and author of Reclaiming American Virtue: The Human Rights Revolution of the 1970s, the answer to the last question should clearly be no. Indeed, for Keys, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “was hardly embedded in American consciousness, but standing for rights could be (and was) easily characterized as a return to long-standing tradition” (p. 240). Yet why did human rights come to occupy such a prominent role in American public discourse and foreign policy in the 1970s? Why were they resuscitated almost 25 years after the adoption of the Universal Declaration? Keys convincingly contends, like Brucken, that human rights rose to prominence to give sense and purpose to U.S. foreign and domestic policies. Replicating an argument formulated in 1985 by the French social thinker Raymond Aron (1993/4, pp. 713-715), human rights became, in Keys’ words, an “antidote to shame and guilt” (p. 3) arising from the trauma suffered from Vietnam War, the Watergate crisis, and the failure of the civil rights movement. Under the Carter Presidency, these anxieties coalesced and allowed the government at the time to elevate human rights to a central component of U.S. foreign policy. Here, Keys’ argument replicate that formulated.

According to Barbara J. Keys, a senior lecturer in American and international history at the University of Melbourne and author of Reclaiming American Virtue: The Human Rights Revolution of the 1970s, the answer to the last question should clearly be no. Indeed, for Keys, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “was hardly embedded in American consciousness, but standing for rights could be (and was) easily characterized as a return to long-standing tradition” (p. 240). Yet why did human rights come to occupy such a prominent role in American public discourse and foreign policy in the 1970s? Why were they resuscitated almost 25 years after the adoption of the Universal Declaration? Keys convincingly contends, like Brucken, that human rights rose to prominence to give sense and purpose to U.S. foreign and domestic policies. Replicating an argument formulated in 1985 by the French social thinker Raymond Aron (1993/4, pp. 713-715), human rights became, in Keys’ words, an “antidote to shame and guilt” (p. 3) arising from the trauma suffered from Vietnam War, the Watergate crisis, and the failure of the civil rights movement. Under the Carter Presidency, these anxieties coalesced and allowed the government at the time to elevate human rights to a central component of U.S. foreign policy. Here, Keys’ argument replicate that formulated.

In Keys’ understanding, human rights were, somehow, perfectly designed to accommodate all views on the American political spectrum. For conservatives, the human rights repertoire offered arguments for denouncing the immorality of communism and alleviate Cold War anxieties in the U.S. Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Soljenitsyn, and countless other communist exiles provided horrifyingly detailed accounts of the functioning of the totalitarian state that only contributed to fostering commitment in favour of human rights. For the liberals, human rights appealed to their faith in U.S. global benevolence and provided ammunition for criticising dictatorships around the world. Human rights thus allowed perspectives to be shifted away from domestic problems and a tenuous political consensus to be reached on core U.S. foreign policy guiding principles by appealing to the idea of right, a concept deeply rooted in American political vernacular.

In Keys’ understanding, human rights were, somehow, perfectly designed to accommodate all views on the American political spectrum. For conservatives, the human rights repertoire offered arguments for denouncing the immorality of communism and alleviate Cold War anxieties in the U.S. Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Soljenitsyn, and countless other communist exiles provided horrifyingly detailed accounts of the functioning of the totalitarian state that only contributed to fostering commitment in favour of human rights. For the liberals, human rights appealed to their faith in U.S. global benevolence and provided ammunition for criticising dictatorships around the world. Human rights thus allowed perspectives to be shifted away from domestic problems and a tenuous political consensus to be reached on core U.S. foreign policy guiding principles by appealing to the idea of right, a concept deeply rooted in American political vernacular.

Keys suggests, however, that the 1970s and Carter’s efforts were mixed. Many NGOs, such as the American branches of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, praised Carter for raising awareness of human rights on a global scale and championing several causes-célèbres. These political postures also reassured domestic constituencies about the morality and virtue of the new government administration. However, in doing so, it not only contributed to the marginalisation of other economic, social, and cultural rights, but also raised scepticism as to the moralising and self-serving nature of human rights in U.S. foreign policy. Domestically, this policy failed to unite the Democratic Party and ultimately weakened U.S. foreign policy by emphasising what was considered by some as a pathological guilt and an unnecessary sense of responsibility towards other countries.

Key’s account opens up the historiographical debate but leaves many interesting questions unanswered. Firstly, how did the rise of global human rights NGOs impact the definition of the human rights project itself?

Brucken and Keys both remain silent as to the impact of U.S. government policies on the definition and the transformation of universal human rights. Secondly, regarding Keys’ argument, how does the mobilisation of the human rights discourse by U.S. officials in the 1970s connect with the rise of neoliberalism in of the Western world at about the same time? Thirdly, how does power and politics translate into human rights provision? This is an important but vexing question for the conception of human rights as advocated by Keys, which appears to borrow from that developed 30 years ago by Michel Foucault in which human rights exist as such if detached from sovereignty: “Amnesty International, Terre des Hommes, and Médecins sans Frontières are initiatives that have created this new right – that of private individuals to effectively intervene in the sphere of international policy and strategy” (Foucault 2000, p. 475). Interestingly, this was a view also advocated, albeit in a different form, by numerous international lawyers in the 1930s and 1940s such as Hersch Lauterpacht.

So, why and how then does the human rights project of the 1970s differ from that of the 1940s as Keys argues? How has this caesura impacted on the construction of the human rights project over the last 60 years?

In closing, Brucken and Keys both offer vigorous, engaging, and methodically crafted accounts of the role and place human rights in the conduct of U.S. foreign policy. They raise important questions and are without a doubt destined to become important milestones in the emerging historiography on that theme.

Brucken, Rowland. 2013. A Most Uncertain Crusade: The United States, the United Nations, and Human Rights, 1941-1953. Dekalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press. 400 pp. Cloth: $48.95. ISBN: 9780875804712.

Keys, Barbara J. 2014. Reclaiming American Virtue: The Human Rights Revolution of the 1970s. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 368 pp. Hb: $29.95. ISBN: 9780674724853.

Bibliography

Aron, R 1993/4, ‘La politique des droits de l’Homme’, Commentaire, no. 64, pp. 705-717.

Foucault, M 2000, Power (Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984), vol. 3, New York, New Press.