Charles Hirschkind. The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics. 288 pages, ISBN: 978-0-231-13819-2.

First published in 2006, the ending paragraph of Charles Hirschkind’s Ethical Soundscapes goes thus: “To speak of Islam today, one necessarily encounters a terrain shaped by deeply entrenched presumptions and anxieties.” This statement holds true today, as the very polarizing views vis-à-vis Islam that Hirschkind tried to address remain central to current political discourse on the region. As such, the book’s stated aim to destabilize entrenched narratives and anxieties about Muslim practices continues to be a salient one. Providing a nuanced and deeper understanding of the “contemporary moral and political landscape of the Middle East,” Hirschkind’s study takes cassette sermons as a point of entry into the analysis of a popular religious revival movement that integrates ethical self-fashioning, political criticism, and communal debate.

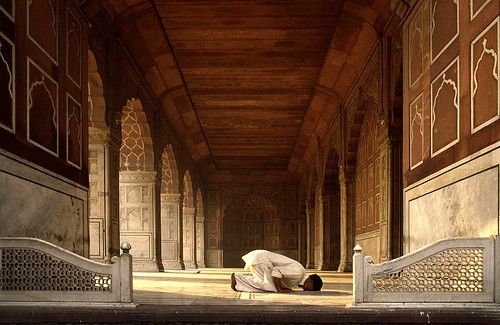

The Ethical Soundscape begins by properly contextualizing what is now widely known as the Islamic Revival movement in Egypt, and traces the historical and political conditions that led to the popularity and widespread use of cassette sermons as a technology for practicing an authenticated form of Islam. The book’s main axis is the role played by cassette sermons in giving birth to what Hirschkind calls “Islamic counterpublics,” and the da’wa movement of summoning one’s peers to act in conformity with God’s will. By showing how the tapes are part of a wider ecology of moral practices meant to foster a pious life, while at the same time acting as part of a project that contests the authority of the Egyptian state, Hirschkind attempts to dismantle the essentializing belief that this medium can only act as a conduit for “militant indoctrination”.  Opening with a history of the “politics of sound” in the region, Hirschkind frames his discussion of an emergent moral and political community within a definition of modernity as a “constellation of practices and technologies contingently connected within discontinuous formations of power.” (p. 21). As such, he can show the continuity between traditional forms of homiletics and the relatively newer technology of the cassette tape. The second chapter carries the argument forward through a history of auditory learning dating back to Ibn Al-Arabi, across a period of state-led consolidation of religious authority, all the way to the present. From an ethnographic and theoretical point of view, Chapter 3 on the ethics of listening provides a gripping account of the potential for an acoustemological approach to the formation of what Hirschkind calls “Islamic counterpublics,” a concept which is then defined at large in the following chapter (cf. Feld and Basso 1996). Listening as an actively embodied state of presence requires an aptitude for receptivity that encourages an affective response. Rooted in the “experience of the body”, the ethical dispositions honed by the taped sermon are seen as a way of augmenting the cognitive sensibilities of listeners and further train the ear to “hear” rather than just perceive (p. 101).

Opening with a history of the “politics of sound” in the region, Hirschkind frames his discussion of an emergent moral and political community within a definition of modernity as a “constellation of practices and technologies contingently connected within discontinuous formations of power.” (p. 21). As such, he can show the continuity between traditional forms of homiletics and the relatively newer technology of the cassette tape. The second chapter carries the argument forward through a history of auditory learning dating back to Ibn Al-Arabi, across a period of state-led consolidation of religious authority, all the way to the present. From an ethnographic and theoretical point of view, Chapter 3 on the ethics of listening provides a gripping account of the potential for an acoustemological approach to the formation of what Hirschkind calls “Islamic counterpublics,” a concept which is then defined at large in the following chapter (cf. Feld and Basso 1996). Listening as an actively embodied state of presence requires an aptitude for receptivity that encourages an affective response. Rooted in the “experience of the body”, the ethical dispositions honed by the taped sermon are seen as a way of augmenting the cognitive sensibilities of listeners and further train the ear to “hear” rather than just perceive (p. 101).

As popular discourse in the West continues to dismiss Islamic religious practice as purely mechanic repetition that produces terrorist subjects (p. 17), Hirschkind’s careful and critical assessment of the Orientalist origins of this bias demonstrate the historically produced nature of a hierarchical scale in which vision was equated with reason and hearing with illusory perception (p. 14).

Countering the misrepresentation of Muslim religious instruction as a unidirectional process, in which a central authority figure dispenses teachings meant to be blindly obeyed, Hirschkind opens the fourth chapter with an ethnographic episode that will seem familiar to those who have spent time or done research in the Middle East. In the space-time of a shared taxi ride, a taped sermon prompts an intergenerational, dialogical exchange about correct religious practice. Hirschkind uses this ethnographical episode to discuss the ways in which the da’wa movement has altered the religious landscape in Egypt since the 1950s, when the Muslim Brotherhood was driven underground by the state. As a consequence, da’wa became a hybrid space linking public activism and moral reform (p. 115). When the Egyptian state is seen to be acting in disaccord with the precepts of a good life promoted by the movement, the cassette sermons become a preferred and perhaps isolated channel for mobilizing the public opinion of the pious (p. 118). The sensorium is once again richly conjured up in Chapter 6, as Hirschkind delves into the “homiletics of death” spread through cassette sermons and paints a wider picture of the close cohabitation of death with life in Cairo’s poorest quarters (p. 177, 195). Western stereotypes of Muslims, Hirschkind accurately points out, tend to focus on what is perceived as a particularly singular obsession with death, “epitomized in the figure of the suicide bomber” (p. 176). Hirschkind rightly links preoccupations with death in Islam with similar traditions in Christianity and Greek philosophical thought, in which death is a “commonplace” that thinkers have often turned to in order for “mortality to be elaborated and lived” (p. 201-203).

The book is most successful in providing a historically and ethnographically grounded description of a growing practice that renders Western distinctions between private and public realms inadequate for capturing the dynamic arena opened up by taped sermons. At the same time, Hirschkind does not try to do away with the complexities and sometimes contradictory aspect of a practice, whose main conduit is the embodied experience of listening.

In acknowledging that cassette sermons can produce both alternative communities as well as create disputes within them, Hirschkind is trying to demonstrate that no moral and political project can be encompassed by a single analytical mold. Instead, he argues, such an “emergent form of public” is a “contingent product”, open and fragile to the forces of markets and institutions, out of which the most important is the regulatory power of the state (p. 108).

Revisiting Ethical Soundscapes three years after the January revolution took place in Egypt, and one year after the removal of a Muslim Brotherhood-backed president, the critical analysis put forth by Hirschkind serves as a reminder for a much needed balanced and careful consideration of Islamic movements. Hirschkind’s observations of pious Muslims’ everyday lives thus echo Asef Bayat’s (2007) call for understanding Islamic religious practice as a fluid moral compass that is adjusted constantly to the rapidly changing socio-economic and political coordinates of life in the twenty-first century.

Cited works

Bayat, Asef (2007): “Radical Religion and the Habitus of the Dispossessed: Does Islamic Militancy Have an Urban Ecology?” in International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Volume 31: 3, pp. 579-90.

Feld, Steven and Basso, Keith (1996): Senses of Place. School of American Research Press.