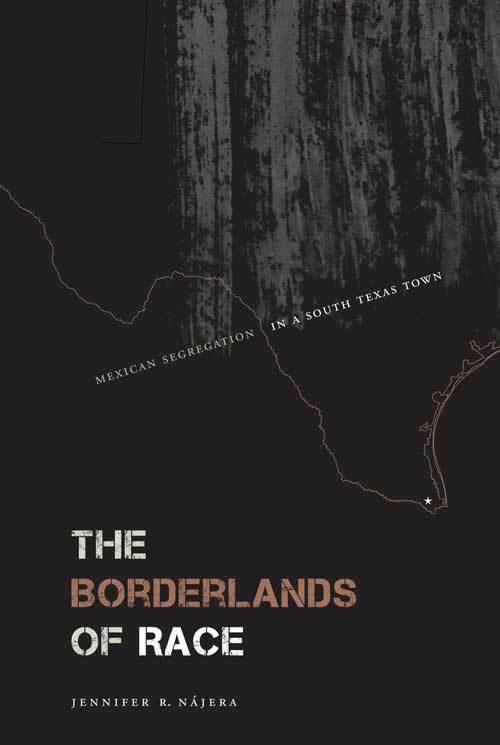

Today we continue our revisitation of 2016 via a review that has – sadly – only grown more topical since it was first published in October 2016: ‘The Borderlands of Race’ by Jennifer Najera, reviewed by David Fazzino. The book discusses the drawing of boundaries and Mexican segregation in a South Texas town. Both the review and the book itself offer much needed context for the current US debate around deportations and walls.

For this thematic week we have selected posts from Allegra’s year 2016 which resonate with the currently unfolding political scene, particularly in the US, jointly assisting us to reach a more nuanced understanding of this peculiar chapter of history.

<<<<

Borders are used as attempts to delineate one particular space from another. In my time along the US-Mexico border (2004-2007) on the Tohono O’odham Nation in Arizona, I learned that talks of border walls, increasing security, and militarization along the US-Mexico border attempted to sharply divide a region which is personally and politically interlinked. Madsen (2007) describes how the border has been continuously recreated both ideologically and materially by various actors (including the U.S. federal government) and indicates some of the implications this has had for the Tohono O’odham. Politicians’ claims of two definitive and distinct countries are not only ahistorical, but continue to have resounding impacts on the Tohono O’odham whose claims to the region supersede those of either the United States or Mexico. Approximately 1000 miles away, Nájera’s work helps unveil another chapter in the long and complicated history of the US-Mexico border and its implications for lived experiences of everyday people.

She examines this at the level of ethnic relations in La Feria, Texas, and the marginalization of Mexican-Americans, who, like the Tohono O’odham, have historical depth to their claims of space.

Nájera’s historical ethnography, covering 1915 through the late 1980s, traverses legal/policy studies, anthropology, oral history, and Chicano Studies in an effort to trace the various forms of segregation Mexican Americans historically experienced in a Texas border town. Nájera shows the slow creep of the legal calls for integration into La Feria and discusses three stages of segregation: establishment in the early 1900s, an accommodated form in the 1940s (including selective incorporation of Mexican Americans into the church and school), a process of diminishment following Chicano and civil rights movements.

In her introduction, Mexican Inflections of Ethnography and History, Nájera situates her work in the context of previous scholarship; indeed, Najera is not the first anthropologist to write about La Feria as she references Arthur J. Rubel’s “standard ethnography” which she critiques as “largely a synchronic account of the Mexican community” (p.1). Unlike Rubel, Nájera has a personal connection to La Feria, which inspires her to root out the de facto racial segregation that was present “most acutely during the first part of the twentieth century” (p.2-3). Drawn from her family’s not-so-fond memories of La Feria, Texas, Nájera works to differentiate how the myriad forms of segregation were experienced.

Nájera finds that race in La Feria was mediated by a number of factors including: socioeconomic status, culture, and skin color.

This is a point she expands upon throughout the first four chapters comprising Part 1: The Culture of Mexican Segregation. Chapter 1, The Borderlands of Race and Rights, explains “shifting racial formations in south Texas history” (p.18), noting that although racial segregation emerged “in the early twentieth century with the arrival of the railroad in South Texas” (p.34) the structure of segregation was complicated by variation in Mexican Americans along the lines of “racial aspects, class status, education, gender, and Anglo cultural fluency” (p.34). Chapter 2, Establishing a Culture of Segregation, covers the structure of segregation between the La Feria’s establishment in 1915 through the 1930s. During this time period there was almost complete separation of Anglo and Mexican communities corresponding to social, political, and economic subordination of most Mexicans. This was reinforced by the town’s schools which provided very different education for Anglo and Mexican children. In Chapter 3, Formal and Informal Mexican Education within the Context of Segregation, Nájera shows how these educational ideologies and practices were resisted through community-based informal education. These community events and activities included mutual-aid societies, teaching children Spanish, and historical and cultural celebrations. Together, Nájera identifies these as “a crucial component in the economic and cultural survival of the Mexican community” (p.57).

In the absence of equal access to the town’s formal institutions (the church and schools) Mexican Americans relied on themselves to carve out meaningful spaces within which they could live their lives.

The 1940s saw a shift from exclusion in public spaces for “exceptional Mexicans” who were “seemingly able to cross racial boundaries (p.84). Nájera, in Chapter 4, An Accommodated Form of Segregation, maintains that “this apparent fluidity actually demonstrates the durability of segregation as it operated through a process of selective and limited incorporation/inclusion” (p.84). It took until the 1960’s for the process of racial integration to begin; this is the focus of Part 2.

In Part 2: Processes of Racial Integration, Nájera considers how everyday people took action in the schools (Chapter 5) and the church (Chapter 6) to racially integrate La Feria. In Chapter 5, Troubling the Culture of School Segregation: Mexican American Teachers and the Path to Desegregation, Nájera shows changing laws to allow for more inclusion in education was less important than the pivotal roles that Mexican American teachers played in challenging discrimination as “these women took upon themselves the everyday work of transforming the culture of segregation into claims for cultural citizenship” (p.112). Nájera defines cultural citizenship as “the right to be culturally different and yet to belong fully,” (p.152) and explores this in the context of both the school and the church. Chapter 6, Surgiendo de la Base: Community Movement and Desegregation of the Catholic Church, highlights how “Mexicans created a cultural relevant religious space for themselves, and from position of religious cultural empowerment, they began to challenge the Anglo hegemony that dominated their local Catholic church” (p.135).

The Borderlands of Race is a rich combination of well-woven archival materials (including maps, photos, schools board minutes, city commissioner records, yearbooks, local newspapers, and property records) and the recollections of lifelong Mexican-American residents of La Feria who experienced mediated forms of segregation and discrimination with varying degrees of intensity. The Borderlands of Race provides a human element to the suffering and slights of those who are deemed less than worthy to fully participate in public life showing the limits of law in the face of long-seated segregation ideologies and practices. Hence, The Borderlands of Race deserves to be read not only for the unveiling of segregation in a South Texas town, as another chapter in the long and complicated history of the border, but also from a methodological perspective as an example of what approach one can take in attempting to get to the previously unrecorded truths of place. From an ethical perspective, these truths are what anthropologists can and should aspire to in planning and conducting their own forays in the field.

The Borderlands of Race is a rich combination of well-woven archival materials (including maps, photos, schools board minutes, city commissioner records, yearbooks, local newspapers, and property records) and the recollections of lifelong Mexican-American residents of La Feria who experienced mediated forms of segregation and discrimination with varying degrees of intensity. The Borderlands of Race provides a human element to the suffering and slights of those who are deemed less than worthy to fully participate in public life showing the limits of law in the face of long-seated segregation ideologies and practices. Hence, The Borderlands of Race deserves to be read not only for the unveiling of segregation in a South Texas town, as another chapter in the long and complicated history of the border, but also from a methodological perspective as an example of what approach one can take in attempting to get to the previously unrecorded truths of place. From an ethical perspective, these truths are what anthropologists can and should aspire to in planning and conducting their own forays in the field.

References:

Madsen, Kenneth D. 2007. Local Impacts of the Balloon Effect of Border Law Enforcement. Geopolitics 12(2): 280-298.

Najera, Jennifer. 2015. The Borderlands of Race: Mexican Segregation in a South Texas Town. University of Texas Press. 195 pp. Hb: $45.00. ISBN: 9780292767553.

**********

Featured image by Hugo Cesar (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This post was first published on 5 October 2016.

Thank you for using one of my photograph to illustrate your review.

Thank you for taking this photo! I hope that we have given you sufficient credit. Please let us know if you want us to add information.

Thank you Judith. Sorry about the very late response to your gracious note. Beside my work as a photojournalist spanning on almost four decades, I am also the author of “The Orwellian Empire”, a journalist, an on air analyst, and a filmmaker