Tansy E. Hoskins. 2014. Stitched Up. The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion. Pluto Press. 256 pp. ISBN: 9780745334561.

Tansy E. Hoskins’ Stitched Up: The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion was published earlier this year as part of Pluto Press’ Counterfire series. In the words of series editor Neil Faulkner written on the opening pages of Hoskins’ book, ‘Counterfire is a socialist organization which campaigns against capitalism, war, and injustice’. On the same page, Faulkner establishes the point of Counterfire producing print publications as ‘to present radical perspectives on history, society, and current affairs to trade unionists, students, activists and everyone concerned about the state of the world’.

That Stitched Up has been put out by Counterfire is instructive. Are students one of the demographics set apart here because they could read books such as Hoskins’ as part of course syllabi or because, instead, they (along with a couple of other groups) exemplify what it is to be ‘concerned about the state of the world?’ Whichever the case, Stitched Up would make an excellent course accompaniment to ethnographic monographs and books on anthropological theory. Even those who reserve sympathy for Hoskins’ politics will be taken by the descriptions of relatively inconspicuous fashion industry workers – from trend forecasters to factory workers.

The point is that the fashion industry is a hauntingly appropriate heuristic for learning about critiques of capitalism. As such, Hoskins’ bibliography is a useful resource for those wanting to read more about Marxist and Marxian thought.

Stitched Up is almost two books in one, or perhaps a book and a pamphlet brought together. Chapters one to seven each centre on a specific aspect of fashion, from the absurdly wealthy multinational conglomerates who each own suites of so-called ‘competing’ designer and high street brands (a section that Jade Pilgrom illustrates with a puppetmaster) to a cultural history of racism in fashion. In contrast, the final three chapters, ‘Resisting Fashion’, ‘Reforming Fashion’, and ‘Revolutionising Fashion’, are intended to capitalise (for want of a better word) on the information set out in previous sections, information that demonstrates how ‘Capitalism should be regarded as a failed system’ (p. 202).

Hoskins is particularly critical of, and writes perhaps most convincingly against, the notion of ‘ethical fashion’: ‘doing good’ through buying.

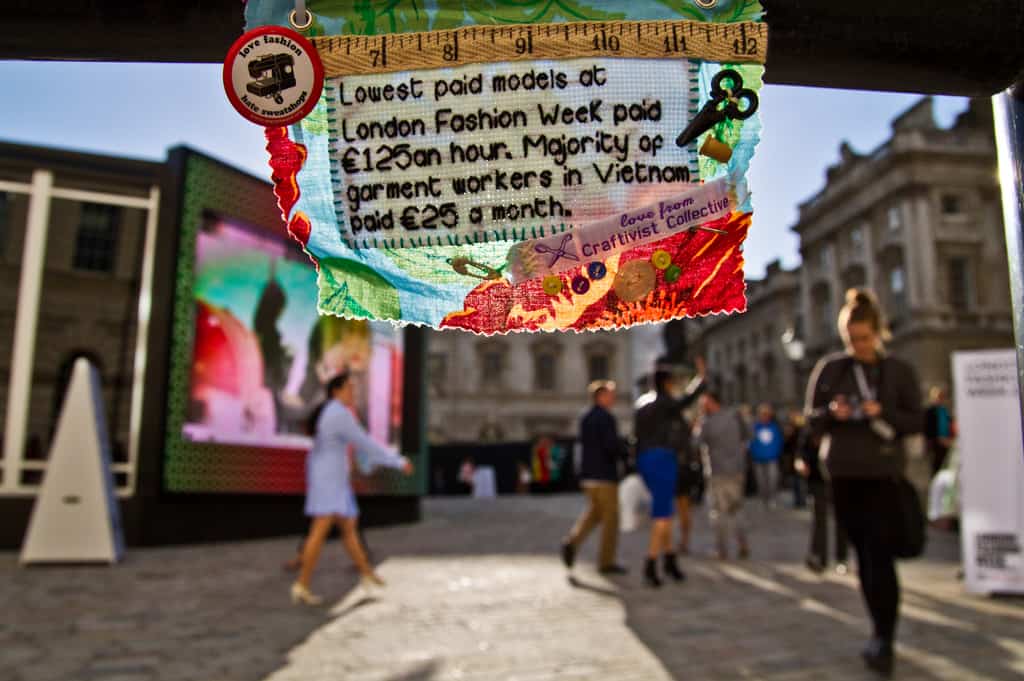

As Hoskins writes, ‘Ethical fashion has become a catch-all phrase encompassing issues such as environmental toxicity, labour rights, air miles, animal cruelty and product sustainability’ (p. 170). This clustering of issues forces consumers to ‘prioritise all the issues thrown up by the industry’ (ibid). People, when cast as ‘consumers’, are baited to ask themselves questions such as ‘Is it better to buy vegetarian shoes made in a Chinese sweatshop or leather from a designer who says fat people are ugly?’ (ibid).

Through ‘causumerism’ (a cousin of ‘slacktivism’?), people are reduced to shoppers, intoxicated by the hype that surrounds certain ‘ethical’ products rather than demanding that all products are produced ethically.

Hoskins’ chapter on the identity politics of clothing, ‘Resisting Fashion’, preempts critiques of her thesis that rest upon clothing’s historical potency as a way of critiquing and rebelling against hegemonic groups. Getting rid of fashion as we know it, which is what Hoskins is proposing, means ‘keep[ing] the good and exorcis[ing] the grim’ (p. 149). It is clear that Hoskins approves of some forms of dress as agents of change. Following Malcolm Barnard, Hoskins divides clothes that seem particularly profuse with meaning into two types of resistance dress: ‘refusal’ and ‘reversal’ (p. 153). In the former, for example, is a brief paragraph on punk: a form of sartorial resistance borne out of ‘the late 1970s and early 1980s, decades when disaffected working-class youth faced rising unemployment and limited opportunities’ (p. 154). Also in this section: the hijab. This receives more attention than punk. Hoskins observes that ‘there is a feeling amongst many Muslim women that they are exhausted by the debate over their dress and that they want to be judged by what’s in their head not what’s on their head’ (p. 155). Putting to the side for a moment the extent to which one feels this is a meaningful appraisal of the politics of veiling – and to be fair to Hoskins, she repeatedly states that is not aiming ‘to write a definitive book of fashion’ (p. 9) – the point Hoskins makes about veiling, that it is a topic of much discussion that leaves less time to talk about – and act on – extra-sartorial politics, is a thread that runs throughout the book. Dress has a part in politics but, to Hoskins, its part needs to be small. ‘Resistance fashion alone’, she writes, ‘does not mount a serious challenge to capitalism’ (p. 164). . Publications and events related to fashion seem particularly thick on the ground at the moment. Currently running at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an exhibition playfully entitled ‘Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire.’ Sheila Heti, Heidi Julavits, and Leanne Shapton’s Women in Clothes has been widely reviewed (although not always positively) and excerpted. Reading such books feels if not a little myopic and silly, then certainly less urgent than the reading of Rana Plaza. We have time to read about both.

When comparing these accounts with Hoskins’ book, however – which I should add are, like Stitched Up, not ‘anthropology books’ – I wonder if writing of ‘Karl Largerfeld and Karl Marx’, as the blurb puts it, misses the opportunity to talk about clothes as intimate and practical objects that factor into households’ and individuals’ economies.

Stitched Up is a gripping and detailed read that, consonant with Counterfire’s aims, is also punchy and accessible. The question is, if fashion is part of capitalism and an apt heuristic for critiquing it, and yet (in the world Hoskins argues for) something that should not be more than this, what are those whom Hoskins has galvanized with this book (a group I am sure is sizeable) supposed to do in order to give rise to change?