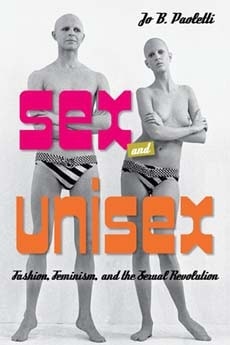

Fashion is deeply expressive of social and individual identities, and thus, changes in fashion trends reveal much about changes in culture. This contention is a familiar one within fashion studies. It is also the premise upon which Jo B. Paoletti presents Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism and the Sexual Revolution, an interdisciplinary examination of the changes in understandings of sexual and gender identity in America during the 1960s and 1970s by way of an historical exploration of the provocative unisex fashion trends of the era. Paoletti’s text is admirable in that it considers a largely unexplored period in American fashion history and therefore provides an original and valuable contribution to the literature. However, while the text employs a well-established methodological fashion studies approach and engages with profoundly interesting subject matter, it is also disappointingly – and ironically, given its focus – out of touch with the fashion studies cannon.

Paoletti’s key focus, as she points out in the introduction, is to attend to the ‘unfinished business of the sexual revolution’ (p.14).

This ‘unfinished business’ is approached through a clearly structured examination of the interconnections between dress and politics and the consequences of such interconnections for the construction of gender and sexual identity. By combining a study of fashion trends with an exploration of the civil rights movement and concurrent trends in the fields of behaviour science, biology and the social sciences, Paoletti not only examines the implications of trends in unisex clothing during the 1960s and 1970s but also positions them as indicative of ongoing culture wars and continued political debates concerning issues of sexuality and gender. Indeed, Paoletti argues that the conflicts of this era expose inherent ‘flaws in our notions of sex, gender and sexuality’ (p.8), flaws that continue to persist due to the fact that the questions raised by the sexual revolution remain to be satisfactorily answered.

This ‘unfinished business’ is approached through a clearly structured examination of the interconnections between dress and politics and the consequences of such interconnections for the construction of gender and sexual identity. By combining a study of fashion trends with an exploration of the civil rights movement and concurrent trends in the fields of behaviour science, biology and the social sciences, Paoletti not only examines the implications of trends in unisex clothing during the 1960s and 1970s but also positions them as indicative of ongoing culture wars and continued political debates concerning issues of sexuality and gender. Indeed, Paoletti argues that the conflicts of this era expose inherent ‘flaws in our notions of sex, gender and sexuality’ (p.8), flaws that continue to persist due to the fact that the questions raised by the sexual revolution remain to be satisfactorily answered.

While Paoletti begins the text with a self-reflexive moment, in which she outlines her own relationship to gender and fashion, she quickly assures the reader that, far from being a memoir based on her own ‘frail memory’ (p.8), the text draws on the fields of dress history, public policy and the science of gender in order to illustrate the arguments. In addition, it uses mass-market catalogs, newspaper and magazine articles, and trade publications as a source of primary data that acts as evidence of trends in unisex fashion. The six chapters of the book each examine a different element of the unisex movement – starting with a chapter exploring the influence of the ‘baby boomers’ on American culture, and progressing through chapters considering womenswear and second wave feminism, menswear and the so-called ‘Peacock Revolution,’ children’s clothes and changing perceptions of nature verses nurture, the litigation of the revolution and bringing fashion into the courtroom, and a concluding chapter examining the implications of this period in relation to contemporary identity politics – yet they all address the same underlying questions concerning how trends in unisex clothing can reveal conflicts concerning sex, sexuality and gender stereotypes

One of the central arguments throughout the text concerns the relationship between masculinity and femininity, specifically how this relationship influences what happens when one or another of these determinations drastically changes.

Where Paoletti’s arguments are at their strongest is in her chapters concerning trends in children’s clothing (based on the work of her 2012 book Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America), and the litigation of fashion trends, particularly the length of boys’ hair and girls’ skirts. As Paoletti rightly notes, there is a significant absence of scholarship on the subject of children’s clothing, and the implications of trends in childrenswear for conceptions of gender and sexual identity. There is also little scholarship on the subject of fashion litigation, despite the fact that the subject has the potential to reveal much about identity politics and the legislation of appearance. Accordingly, Paoletti’s chapters on both subjects are particularly fascinating. The strength of these chapters is also enhanced by the critical evidential illustration that is frequently lacking elsewhere in the text.

The themes with which Paoletti engages are important, the arguments she posits are provokingly posed, and there is sufficient contemporary relevance to render the work revealing and meaningful.

However, at times the contentions advanced appear shallow or even superficial due to the clichéd nature of numerous claims that lack nuanced engagement with the critical literature. When she notes that ‘miniskirts rose inch by inch, and school dress codes followed them, resignedly’ (p.30), or that neckties have ‘been a feature of women’s fashion for centuries’ (p.51), or that the ‘peacock “revolution” was turning into a civil war’ (p.76), the generalised nature of her statements, lacking evidential support, undermines the rigor of the work and tends to diminish the strength of Paoletti’s arguments. While the text includes numerous case studies that eloquently illustrate and support Paoletti’s contentions (particularly in chapters four and five), they are interspersed with generalised and unsubstantiated assertions that question whether Paoletti has succeeded in producing a text that avoids ‘oversimplification or confusion’ (p.14).

Further, while the book deals with the subject of fashion deeply and sincerely, it lacks critical engagement with fashion theory, engagement that could have further extended the scope of the research. As a fashion scholar reading a text in which ‘Fashion’ features in the title, it was surprising to note the lack of fashion scholars referenced. Indeed, even the most well-known fashion scholar, Elizabeth Wilson, is not mentioned, despite the fact that her seminal text Adorned in Dreams (1985) includes chapters on both ‘Gender and Identity’ and ‘Oppositional Dress.’ Wilson is not, however, the only scholar to discuss androgynous, unisex fashions, and the ways in which changes in dress trends reflect social and cultural changes. Rather, these are common themes in scholarly fashion literature. Thus, while Paoletti’s book is a timely reading of an interesting and influential period in recent American history, her arguments would have benefitted greatly from critical engagement with the work of fashion scholars whose work has also considered the subjects with which she is concerned.

References:

Wilson, Elizabeth. 1985. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. London: Virago Press.

Paoletti, Jo B. 2015. Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution, Indiana University Press, Indiana, 216 pp. US$25.00 ISBN: 978-0-253-01596-9.

**********

Featured image (cropped) by Tom Magliery (flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)