Anthropology is quite familiar with enculturation and the informal processes by which culture is constructed and transmitted. Increasingly, however, culture is made and diffused very formally by cadres of ‘experts’ who, internationally speaking, circulate a globalised language of medicine and therapy (see e.g. Adams and Pigg (2005) on the scientific discourse of sex and sexual health).

Specific concepts like ‘trauma’ are not only carried by these experts but become vernacularised as local people learn to perceive themselves and their circumstances through such concepts.

Thus a new notion of ‘normality’ is offered and absorbed as experts, both foreign and domestic, not only train ordinary people in the language of therapy but train trainers to collaborate in spreading the new normal.

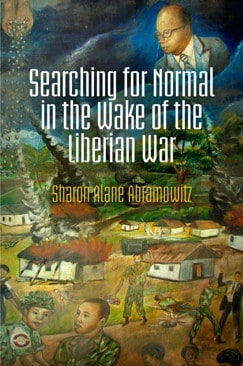

Sharon Alane Abramowitz’s new study on post-war Liberia brings together many contemporary streams of social research on war, post-conflict reconciliation, psychological theories and therapies, NGOs, and gender violence to name but a few. Her focus is on “the ‘superstructure’ of trauma, especially the psychiatrically oriented pacification that has been present but made invisible in the history of military interventions in Africa and elsewhere” which, despite being internationally funded and driven by a standard psychological model of wellness and trauma, has been remarkably “uncoordinated, decentralised, ad hoc, and ambivalent” (p. 5). She argues persuasively that various actors and institutions have introduced “the language of trauma, healing, and recovery” to promote “peace subjectivities” among Liberians, not so much to cure them of the damage of war as to allow them “to manage and mitigate” that damage (p. 6, emphasis in the original).

Sharon Alane Abramowitz’s new study on post-war Liberia brings together many contemporary streams of social research on war, post-conflict reconciliation, psychological theories and therapies, NGOs, and gender violence to name but a few. Her focus is on “the ‘superstructure’ of trauma, especially the psychiatrically oriented pacification that has been present but made invisible in the history of military interventions in Africa and elsewhere” which, despite being internationally funded and driven by a standard psychological model of wellness and trauma, has been remarkably “uncoordinated, decentralised, ad hoc, and ambivalent” (p. 5). She argues persuasively that various actors and institutions have introduced “the language of trauma, healing, and recovery” to promote “peace subjectivities” among Liberians, not so much to cure them of the damage of war as to allow them “to manage and mitigate” that damage (p. 6, emphasis in the original).

The psychological scars and social habits of war are very much with Liberians some years after the cessation of combat, naturally evoking a therapeutic response from Western-inspired agencies like the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL). Abramowitz first traces the history of therapeutic interventions in the country, from 1994 until 2006 when, surprisingly, “most NGOs had ceased mental health and trauma-healing activities, and were intensely averse to providing financial, labor, or logistical support for mental health or psychiatric services” (p. 34). Early efforts by the World Health Organization and similar groups were aimed at communities rather than individuals and emphasised training local trainers, embedding the discourse of trauma and recovery in the culture. The description confirms her conclusion that initiatives were inconsistent, sporadic, and troubled by institutional and personal differences, such that by 2010 Liberian national mental health policy had become a ‘non-event.’

In the third and fourth chapters Abramowitz combines theoretical/conceptual and ethnographic materials to paint a picture of the ‘new normal’ that was taught by legions of (often ill-trained and off-script) ‘experts’ and learned by laypeople.

Incorporating a curious blend of medical and moral talk, Liberians were encouraged “to manage their memories” and “to seek out and assume new habits of speech, behavior, and principles of interaction” (p. 65).

The modern ‘psychosocial’ model also confronted a local traditional concept – a culturally-specific syndrome – called Open Mole, in which victims complained of a softness or sinking of the top of their skull accompanied by symptoms including “self-isolation, aural and visual hallucinations, depression, suicidal ideation, and anxiety” (p. 105). Interestingly, but consistent with other cross-cultural findings, the vast majority of sufferers of this syndrome were women.

Raising the issue of gender leads Abramowitz to turn to the gender-based violence experienced during and after the war in the next chapter. Compared to other psychosocial interventions, she judges gender-based violence projects to be much more efficient, effective, and coordinated – so much so that she perceives an effort to establish a ‘gender-based violence proxy’ for the fading and failed mental-health and trauma-recovery schemes. Once again she recounts a noteworthy conflation of “humanitarian culture and Liberian culture” (p. 141) in which local people trained by NGOs went out among their fellow citizens as experts with a syncretic message of medical, legal, and moral advice – not all of it accurate.

Naturally, the other main target-group of intervention was ex-combatants, who posed an obvious danger during the war and an ongoing danger afterwards. The trauma experienced by child soldiers in neighboring Sierra Leone and the problem of reintegrating them into society was memorably portrayed in Ishmael Beah’s (2007) A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. In Liberia, UNMIL led the process of Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration (DDRR) with the goal of “deconstructing ‘security-mindedness’ and replacing it with peace subjectivities” (p. 159), and to illustrate the point Abramowitz describes the activities of National Ex-Combatant Peacebuilding Initiative (NEPI) trainers among a group of former fighters squatting on a local plantation.

Toward the end of the book, Abramowitz rightly characterises such projects as ‘social engineering’ and the formation of a new sense of time, a ‘redemption time,’ even a ‘messianic time’ (p. 184). She highlights again how discourses of law, human rights, and religious morality get enmeshed in the ‘training’ that ‘experts’ deliver to citizens. In these ‘rituals of reconciliation,’ the recovery process was envisioned to “follow a trajectory of admission, confession, expiation, and forgiveness” (p. 205), and in order to facilitate this outcome the trainers – or ‘healers,’ as she regards them in the final chapter – must themselves undergo a psychosocial transformation before they can transform others. At the very end she studies the experience of becoming a Liberian psychosocial worker and the motivations for specific individuals to assume this role. For many, understandably, it was initially simply a job, but for most it eventually became “a kind of moral reeducation” (p. 220).

Other research (e.g. Hinton 2010 ; Wilson 2003) has explored the processes and outcomes of transitional justice and national reconciliation, and Djo Tunda Wa Munga’s (2010) film State of Mind: Healing Trauma depicts a particular American psychologist, Albert Pesso, practicing his Pesso Boyden System Psychomotor method on post-conflict Rwandans.

Abramowitz’s work is unique and important, however, for documenting the wider cultural absorption of a formal, expert-driven (if not always entirely competent) discourse and practice that essentially sought to remake individuals and collective society in psychosocial and medical terms. Its analysis of the complex networks of institutions, agencies, and individual professionals provides a compelling case study of how all sorts of globalised interventions, like disaster-relief programs or the sexual-health project mentioned at the outset, operate in the contemporary world.

Adams, Vincanne and Stacy Leigh Pigg, eds. 2005. Sex in Development: Science, Sexuality, and Morality in Global Perspective. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Beah, Ishmael. 2007. A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. New York: Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Hinton, Alexander Laban, ed. 2010. Transitional Justice: Global Mechanisms and Local Realities after Genocide and Mass Violence. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Munga, Djo Tunda Wa. 2010. State of Mind: Healing Trauma. Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films.

Wilson, Richard Ashby. 2003. “Anthropological Studies of National Reconciliation Processes.” Anthropological Theory 3 (3): 367-87.

Jack David Eller also reviewed State of Mind: Healing Trauma, a film on healing after trauma from African war.

Abramowitz, Sharon Alane. 2014. Searching for Normal in the Wake of the Liberian War. Series: Pennsylvania Studies in Human Rights. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. 268 pp. Cloth: £42.50. ISBN 978-0-8122-4626-1.