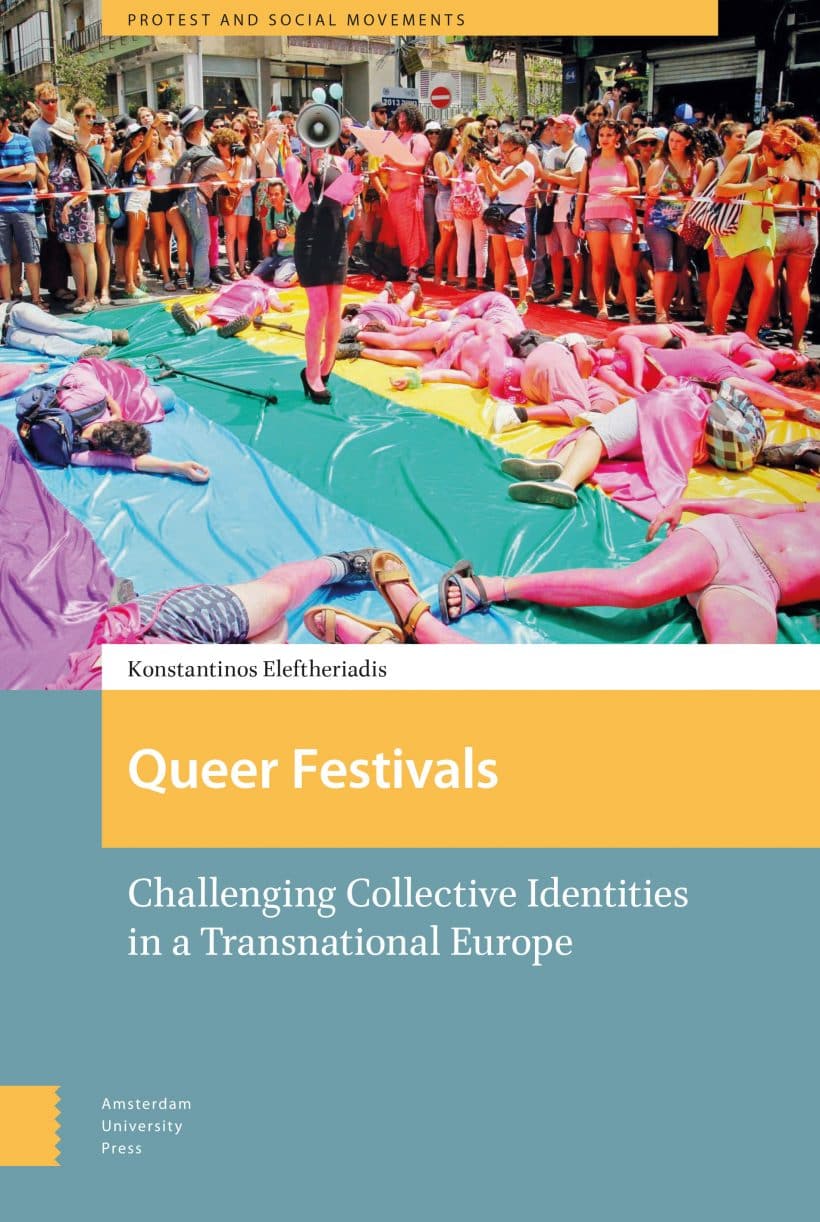

Konstantinos Eleftheriadis’s Queer Festivals: Challenging Collective Identities in a Transnational Europe is a much needed and welcome addition to a small but growing body of critical literature that examines the impact of queer theory and politics in a European context. Eleftheriadis’s book examines how anti-identitarian politics informs collective movements as found in queer festivals in Western Europe, and in particular, addresses the question: “[h]ow is it possible for a collective identity to be anti-identitarian?” (15). Through the book’s six chapters, Eleftheriadis lays out a convincing case for how to approach social movements that refute gender and sexual binaries and do not engage with the state through rights-based advocacy, focusing instead on deconstructive, queer, and anti-capitalist forms of social activism. Much of the literature examining queer theory and queer praxis in Europe focuses on national level, often sidelining or only tacitly acknowledging how queerness transgresses boundaries: gendered, sexual, and national.

Eleftheriadis’s examination of the transnational character of queer festivals hence stands as the book’s strength.

Queer Festivals is laid out in a very logical, direct manner and the author’s thorough engagement with the significant theories is one of the text’s strengths. This allows readers who are unfamiliar with the works of Butler and Foucault to quickly understand their theoretical positions and influence on contemporary queer activism. The only drawback is that the theoretical foundations for anti-identitarian politics are repeated in each chapter. For readers who are well-versed in queer theory, much of this scholarship will be familiar. However, I suspect that for the author’s target audience, social movement theorists and sociologists based in Europe, the added emphasis will be welcome.

The book begins with an introduction to queer festivals, anti-identitarian politics, and the author’s methods and approach to the subject, which is followed by a description of the emergence of queer festivals – from their origins in ACT UP/Queer Nation in the late 1980s/early 1990s in the United States to the more recent Queeruption festivals in the UK. This chapter is a particularly worthwhile contribution to contemporary scholarship on queer activism. Eleftheriadis’s book represents one of a handful of scholarly texts that address queer activism outside of a North American context, and in particular on a transnational scale. Elsewhere in the book the author examines the influence of squatting culture on queer festival spaces, the ways that anti-identitarian politics influence the types of workshops, DIY (do-it-yourself) initiatives such as non-hierarchical forms of organising, and collective vegan cooking practices, as well as the types of dress and styles that are present among participants.

The text illuminates one critical divergence in queer festivals that continues to haunt queer theory – its relative elitist nature.

In particular, it shows how the field has become institutionalised in academia, in contrast to the anti-elitism of queer praxis, which focuses on engaging individuals on a personal, anti-hierarchical level. Queer Festivals frequently points out the real-world implications of such a divergence: for example, how the language of queer festivals is inaccessible to those who do not have the academic background or knowledge of key texts such as Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble. The author also points to the a priori acceptance of queer theory as “the ideological source” of the queer movement and the inherent elitism that this entails. This is best illustrated in how queer theory’s “authority is promoted through actors who are trained in it and disseminate it inside the festivals” (122), while those who have not had access to higher education or taken courses in queer theory remain marginalised.

This insight points to a significant gap in current scholarship – how queer theory, and in particular, specific intellectual figures and their scholarship, find their way into different activist groups in different geographical contexts.

However, Queer Festivals only tacitly addresses the transnational movements of queer theory, though I do acknowledge that this was not the central theoretical question of the text. I was also left wondering about the central distinction that the author draws between queer theory in a North American context and its uptake in Europe. Eleftheriadis expands on how queer theory as a field developed in the United States, which then travelled to the UK, Scandinavia, and then elsewhere in Europe through processes of “transnational diffusion,” as “a series of discontinuities, retransformations, adaptations and challenges” (44). If there is such a distinction between American and European queer activism, it would have profited from further development. While Eleftheriadis links the emergence of queer political activism in the United States to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, and acknowledges activism that it inspired in certain European contexts (for example, ACT UP Paris), his attempt to make a clear distinction of European queer festivals to global justice movements of the 2000s and anti-capitalist politics overlooks how similar forms of politics emerged in the United States during the same period, such as Occupy, the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement, and similar anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist forms of political activism.

However, Queer Festivals only tacitly addresses the transnational movements of queer theory, though I do acknowledge that this was not the central theoretical question of the text. I was also left wondering about the central distinction that the author draws between queer theory in a North American context and its uptake in Europe. Eleftheriadis expands on how queer theory as a field developed in the United States, which then travelled to the UK, Scandinavia, and then elsewhere in Europe through processes of “transnational diffusion,” as “a series of discontinuities, retransformations, adaptations and challenges” (44). If there is such a distinction between American and European queer activism, it would have profited from further development. While Eleftheriadis links the emergence of queer political activism in the United States to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, and acknowledges activism that it inspired in certain European contexts (for example, ACT UP Paris), his attempt to make a clear distinction of European queer festivals to global justice movements of the 2000s and anti-capitalist politics overlooks how similar forms of politics emerged in the United States during the same period, such as Occupy, the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement, and similar anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist forms of political activism.

While the author argues that queer theory’s emergence was through its “circulation” in academia, particularly in countries where queer theory was not being actively produced but synthesised and taught, his analysis would have benefited from further examination of how queer theory emerged in specific local contexts. For example, there is a growing body of literature coming out of Central and Eastern Europe that traces the problematic nature of queer theory as a form of social and academic capital. Eleftheriadis’s text only briefly gestures to this body of work. The book would have also profited from a more thorough engagement with recent queer theory that challenges and problematises the anti-normative core of queer scholarship.

Despite these drawbacks, Queer Festivals is a highly engaging, well thought out and well-written piece of scholarship on queer transnationalism. For scholars such as myself who study the impact of queer theory outside of North American and Western European academic institutions, the questions posed by Eleftheriadis’s book and his incisive observations are a valuable contribution to both queer scholarship and social movement studies.

Reference

Featured Image by rihaij (Courtesy of Pixabay)