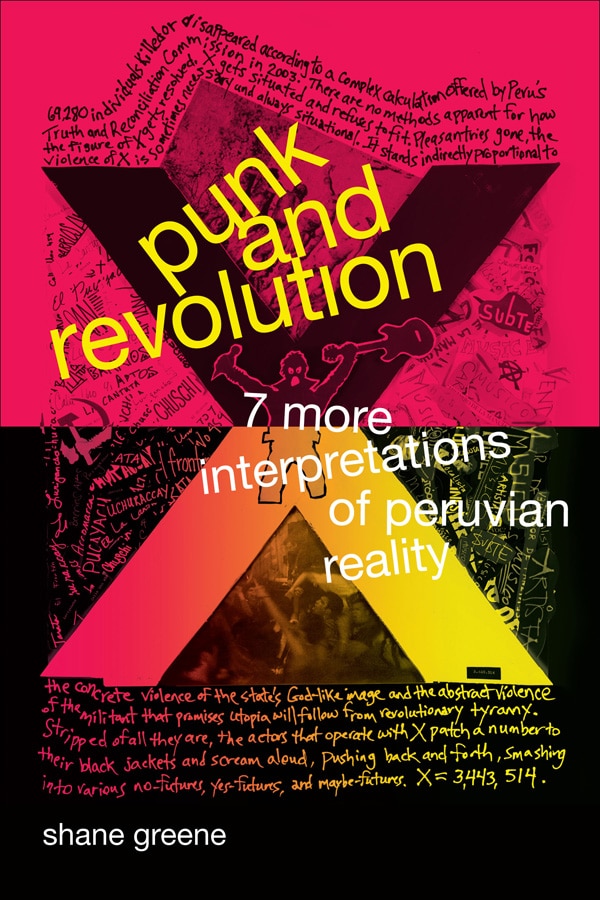

In Punk and revolution: Seven more interpretations of Peruvian reality, Shane Greene locates the distinctive elements of Peruvian punk in the context of the political and urban environment of the 1980s and early 1990s. This time, which Greene refers to as “the bloodiest period since independence from Spain” (1) is shaped by the Communist Party of Peru, also known as the Shining Path, and is dominated by migration, race and class conflicts. He points to the autonomous and revolutionary character of the Peruvian punk, which is used for political resistance through music and art. Instead of trying to define “punk,” Greene examines how the Peruvian punk emerged in its particular form. Thereby he dislocates punk from its familiar place “in the history of Anglo popular music forms and the Euro-American avant-garde“(5) and reflects on punk and its meaning in this particular historical moment.

In Punk and revolution: Seven more interpretations of Peruvian reality, Shane Greene locates the distinctive elements of Peruvian punk in the context of the political and urban environment of the 1980s and early 1990s. This time, which Greene refers to as “the bloodiest period since independence from Spain” (1) is shaped by the Communist Party of Peru, also known as the Shining Path, and is dominated by migration, race and class conflicts. He points to the autonomous and revolutionary character of the Peruvian punk, which is used for political resistance through music and art. Instead of trying to define “punk,” Greene examines how the Peruvian punk emerged in its particular form. Thereby he dislocates punk from its familiar place “in the history of Anglo popular music forms and the Euro-American avant-garde“(5) and reflects on punk and its meaning in this particular historical moment.

Although the global Punk movement is often seen as uniform, a closer look at the origins and musical characteristics reveals the unique nature of every punk scene. Greene’s study of the Peruvian punk scene is illustrative of this. Greene’s work resonates with my ethnographic research with a Punk collective in Yangon, in which I examine the processes of “becoming” among activists amidst Myanmar’s political and social changes.

While following different activist projects that are led by this punk collective, I observed how their punk is shaped by Myanmar’s social and political issues.

Through the use of lyrics, visual artworks, interviews and fieldnotes Greene offers an archival project that is divided into seven interpretations. In the first chapter, interpretation #1, Greene states that punk in itself cannot be defined, but what punk is striving to achieve can be described. The rock subterráneo, where the underground punk rock scene of Lima is located, was using different elements like homemade technology out of second-hand electronic devices and samples from the audio of propaganda to channel their creativity into their music as a way of revolution. With the case study of Narcosis, one of the first Lima punk bands, and its first record Primera Dosis, the author’s interpretation takes the reader through the process of production in the DIY (Do It Yourself – a basic punk principle) spirit. Primera Dosis is a Marquetta (18), a music cassette that already is a substitution. This stands in opposition to vinyl, which was not accessible for the rock subterráneo. Here Greene opens up a contrast between Punk in the Global South and Punk in the Global North. The North was listening mainly to vinyl, the South mainly to cassettes. The Marquetta was produced as music cassettes which were essentially already duplicates, replicating the copy of a copy of a copy. The author is tracing some influences from the Global North punk that already came to Lima as copies of copies.

At this point the question came to my mind – “when can a copy still be called a copy and not something new?”

It has started to emerge in my research on punk in Myanmar that not enough consideration has been afforded to this dichotomy between at what stage mimicry becomes originality. Drawing on Greene’s theory, this binary misunderstands the origins of the individual punk scenes and styles.

Bringing in Marxist theory about overproduction, Greene’s ethnography also illustrates how the music of the rock subterráneo is used in opposition; for underproduction as a revolutionary tool. This interpretative approach concludes in the second reading, when Greene states that punk aims to underfuck the system (48).

He moves on to investigate in-depth how this scene was divided, along with gender, race, class and spatial divisions. The ethnography brings punk rock shows from the 1980s back to life. Within these shows, the author reconstructs the conflicts with the surrounding environment outside and the conflicts within the underground scene.

Greene goes on to dig deeper into the Punk scene and reveals strong and deep divisions which split the rock subterráneo into two camps. On the one side are the pituco-punks and on the other side the cholo-punks (56). These terms refer to antagonisms coming from race, class and spatial divisions among the members of the underground scene. To explain the pituco-cholo-conflict to the reader Greene takes it back to historical developments, which reveal the class, race and spatial origins of the conflict. Although there is already a strong division between two camps, a gender aspect adds dimension in interpretation #4. The Peruvian punk scene was male-dominated and rife with gender struggles. Within the context of everyday, grappling with gender became a secondary problem to the real problems related to class and race politics that the members of the scene rebelled against.

As an example, Greene introduces the reader to Maria T-Ta. Maria T-Ta, a female Punk artist, used feminist slapstick (p. 98) in her songs and performances, proclaiming body and sex-positivity. Her attempts to creatively represent the issues that drove her engagement in the scene were met with strong resistance by the male scene members. In the case study of Maria T-Ta, the author also makes clear how much state repression and police violence the scene members had to face.

Maria T-Ta, as an outspoken and visible female punk, had to deal with issues of repression and violence inside and outside the scene.

Greene closes the circle by adding a chapter, where he shifts into the past decade, starting from 2010. There Greene explores the reunion concerts of the 1980s punk bands and subsequent nostalgia. The last two interpretations of the ethnography consist of fieldnotes, an art project, and a philosophical drunken dialogue about punk’s constant death, rebirth, and metamorphosis.

Starting as early as the third line of the introduction chapter with “anyone dumb enough to think” (1), Greene’s vocabulary is interspersed with unconventional language for academic publications. There is no hesitation in using the word fuck in various contexts to make points clear and add another dimension to the interpretation. The content of the book focuses on specific terms and their usage, on symbolisms and the underproduction of music and art as revolutionary tools.

Whether intended or not, the chapter about punk’s gender dimension in the Peruvian context is the centerpiece of the book. The chapter unites music and art as revolutionary tools while both are common targets of repression and violence by fellow scene members as well as state actors such as the police. This essay unites the single elements of the ethnography and reveals a dimension where revolution and repression collide, and where the scene mirrors the political and social environment they rebel against.

Punk and revolution is the academic part of a series of publications that reflect a part of the history of Peruvian punk. In addition, readers can access related artworks to the book on Peruvian punk by Greene and a collection of punk rock music that is also discussed in the ethnography via www.punkandrevolution.com. This features an ethnography including a soundtrack which was already composed in the 1980s.

Greene, Shane (2016). Punk and Revolution. Seven more Interpretations of Peruvian reality. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

All photographs by Ludvine Paques