This seamless compilation of essays has the feel of a life’s work. Through the lens of his scholarship on the Yoruba, Andrew Apter tackles debates in anthropology of Africa, on culture – as concept, possibility, and conceptual possibility, on colonialism and postcolonialism, ethnogenesis, and “metadiscursive construction[s]” (8) about something one might dare try and call Yoruba object-culture-tradition.

Immersed in deconstruction at the start of his academic pursuits as a student of philosophy, Apter has experienced the politics of knowledge production in the postmodern moment, and gently pokes at the complete decentering of the subject (and everything else, of course) by looking towards Kant, and “winking” at Ryle in the Introduction.

Beginning with perhaps the largest shadow still cast over the institutionalization of Africanist scholarship in the United States, Apter recovers and reformulates core elements of the syncretism framework through a sympathetic critical evaluation of the work of Melville Herskovits on acculturation and continuities from Africa (especially West Africa), in the African Americas. The general thrust is that the dynamics of creolization and hybridization—attributed variously to, for e.g., retentions of cultural practices from the homeland or creative formulations produced on slave ships and plantations—are internal to the dynamic deep knowledge paradigm of Yoruba religion and politics itself.

Beginning with perhaps the largest shadow still cast over the institutionalization of Africanist scholarship in the United States, Apter recovers and reformulates core elements of the syncretism framework through a sympathetic critical evaluation of the work of Melville Herskovits on acculturation and continuities from Africa (especially West Africa), in the African Americas. The general thrust is that the dynamics of creolization and hybridization—attributed variously to, for e.g., retentions of cultural practices from the homeland or creative formulations produced on slave ships and plantations—are internal to the dynamic deep knowledge paradigm of Yoruba religion and politics itself.

Apter achieves this through historical reevaluations of New World syncretism (via Herskovits, Ch. 1), the “notion of origins” (40) in African diaspora research (via the “Petwo Paradox,” Ch. 2), creolization (via the construction of gender, Ch. 4), documentation (of orisha cults and Epa masquerades from Ekiti Yoruba highlands, Ch. 3), and the immanence of hybridity within Yoruba religion (Ch. 5).

For instance, in Chapter 2, Apter delves into the Petwo Paradox: how gods that are high and cool in one context, also become low and hot in another; how the sacred and pure on the one hand, and money and sorcery on the other, can be associated with the same gods; how Vodou in Haiti can be considered creolized, and re-considered creolized from a perspective that takes as its point of departure a “West African hermeneutics of power” (65). Continuing with the dynamics of creolization in the realm of constructions of gender, motherhood and womanhood, Apter identifies demographic, cross-ethnic communicative, and European factors in the emergence of an Afro-Atlantic African American set of constructions (Ch. 4: The Blood of Mothers).

Nevertheless, it is not a very heady mix; Apter is not inclined towards grand theoretical forays. Odudwa’s Chain is focused instead on methodological correctives to the scholarly framework of African Studies.

Empirical questions and the scholarly terrain relating to them are explained with simplicity and clarity borne of scholarly labor.

No Africanist myself, I was able to comprehend the trajectory of his argument and consider how it might relate to areas of my own interest: race, the Black Experience in the United States and studies thereof.

If there is a line to the African American experience that runs to and through Odudwa’s Chain, what does this imply for action and scholarship about African American identity, experience, and cultural forms? Does this, at the very least, recover historically a strand that allows a conversation about “African American culture,” without being accused of bringing in essentialized stereotypes about black folk in through the back door? I will not have a personal answer for a few years yet, but there is an opening here for the discussion to be renewed.

Beyond anthropology, the book will be of interest to scholars in African Studies, Black Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Gender Studies.

Advanced classes in African Studies might benefit from specific chapters as well. Starting with an essay originally published in 1991 speaks to a continuity in the author’s predilections, but also to the continued relevance of this debate about origins, about Africa as source vs. Africa as mythical reservoir. The issue remains unsettled, and since the controversy over Daniel Patrick Moynahan’s “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” largely dormant through a studied silence (in my view). Africanists will decide whether this call is heeded, and thus also on the substantive import and impact of Odudwa’s Chain as a whole.

Chapter Overview

Chapter 1, “Herskovits’s Heritage,” contextualizes and evaluates Melville Herskovits’s study of the African origins of New World religious and cultural practices among the Black diaspora. Taking him to task for a static concept of culture and a lack of attention to the dynamics of class and power, Apter nonetheless finds that it is possible to recover a useful framework of study and analysis for the Black Atlantic today.

In Chapter 2, “Creolization and Connaisance,” Apter delves into the Petwo Paradox: how gods that are high and cool in one context, also become low and hot in another; how the sacred and pure on one hand, and money and sorcery on the other, can be associated with the same gods; how Vodou in Haiti can be considered creolized, and re-considered creolized from a perspective that takes as its point of departure a “West African hermeneutics of power” (65).

Chapter 3, “Notes from Ekitiland,” serves a documentary function for the religious practices in Ekiti Highlands, and continues the methodological reformulation which is the larger intent of the book. Apter finds that there are greater similarities in Yoruba orisha worship and related religious practices in the New World than previously considered. This perspectival realignment should also inform studies of Yoruba religion as a global phenomenon.

Chapter 4, “The Blood of Mothers,” examines the constructions of gender and how menstrual blood and motherhood are inscribed in the dialectics of “social relations of production and reproduction” (98) in plantation societies built on multiple forms of forced labor.

References

Apter, Andrew. 2018. Odudwa’s Chain: Locations of Culture in the Yoruba-Atlantic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

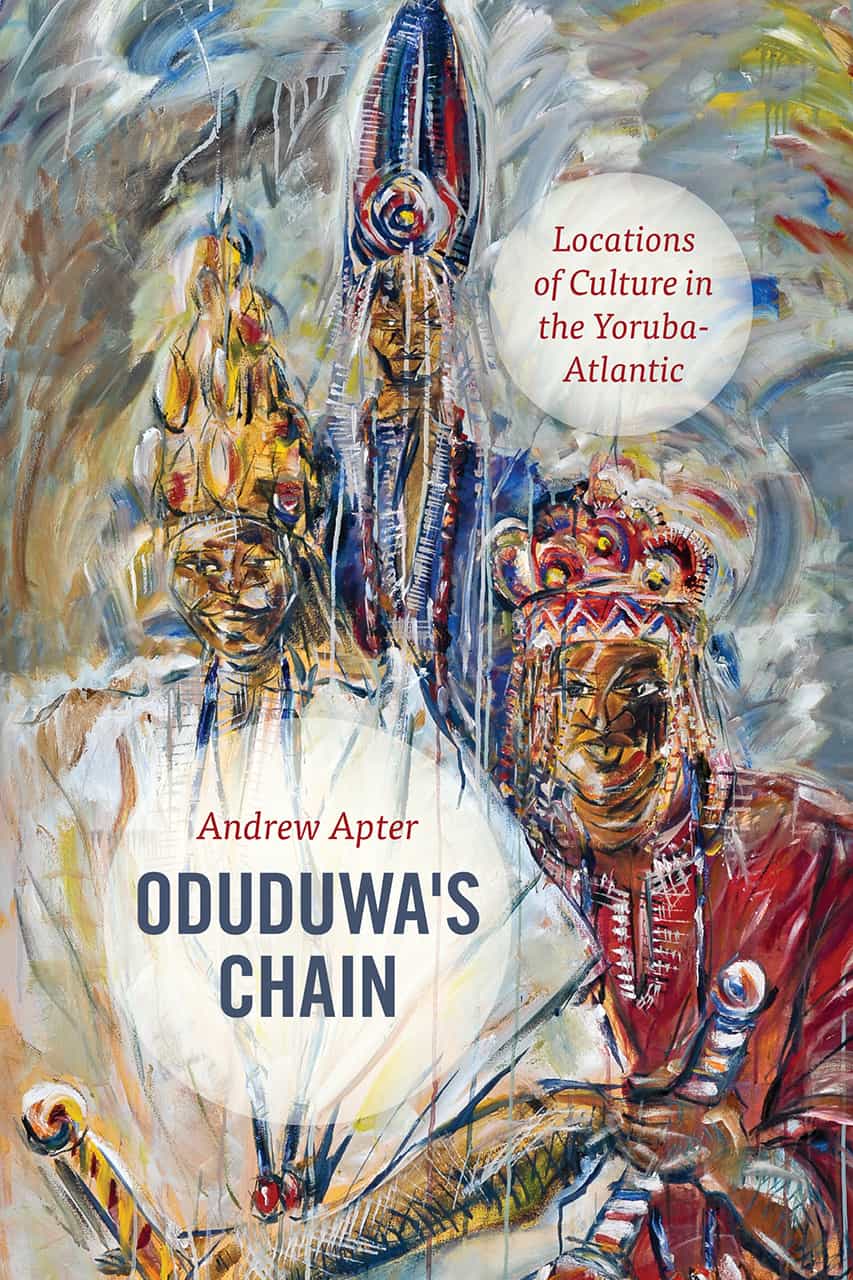

Featured image (cropped): The Gelede Masked Festival of Cové, Benin. Courtesy of Grete Howard, CC BY 3.0 (via wikimedia commons).