Established in 1994, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), along with its predecessor, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), was, at the time of its inception, the most significant effort of international criminal justice after the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials. The ICTR was an ambitious project of the international community to hold accountable perpetrators of mass atrocities, as well as a much-delayed reaction of the United Nations Security Council to the genocide in Rwanda. Genocide Never Sleeps: Living Law at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda chronicles the social life of the ICTR, based on two years of ethnographic research conducted between 2005 and 2007, eight months of which were spent in the ICTR’s premises in Arusha, Tanzania. Through “deep hanging out” (p. 23) at the scene of this complex project of transnational justice, Nigel Eltringham takes us inside the ICTR and demonstrates the inner, often quite messy, workings of the tribunal which contrast with its distant, usually sterile, depictions found in official proclamations.

Established in 1994, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), along with its predecessor, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), was, at the time of its inception, the most significant effort of international criminal justice after the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials. The ICTR was an ambitious project of the international community to hold accountable perpetrators of mass atrocities, as well as a much-delayed reaction of the United Nations Security Council to the genocide in Rwanda. Genocide Never Sleeps: Living Law at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda chronicles the social life of the ICTR, based on two years of ethnographic research conducted between 2005 and 2007, eight months of which were spent in the ICTR’s premises in Arusha, Tanzania. Through “deep hanging out” (p. 23) at the scene of this complex project of transnational justice, Nigel Eltringham takes us inside the ICTR and demonstrates the inner, often quite messy, workings of the tribunal which contrast with its distant, usually sterile, depictions found in official proclamations.

Nigel Eltringham takes us inside the ICTR and demonstrates the inner, often quite messy, workings of the tribunal which contrast with its distant, usually sterile, depictions found in official proclamations

In five carefully constructed chapters, each of which expounds a facet of the tribunal’s work (lawyers and judges’ assessments of the tribunal’s purpose and legacy; the spatial and visual dimensions of the proceedings; challenges to the “hidden script” of habitual legal practice; the problematic construction of legal truth and evidence in witness testimonies; and law’s role in producing a historical record vs. determining guilt or innocence), Eltringham diligently demonstrates the arduous process of bringing international criminal law to life. Though Eltringham is an anthropologist by training, and provides extensive coverage of political and legal anthropological literature in this study, the book is also addressed to legal scholars. More specifically, Eltringham is critical of the body of international criminal law scholarship that has been dominated by textual analyses of law without much interest in the day-to-day work that sustains tribunals. Instead, by focusing on the people, rather than the rules and regulations, that bring law to life, Eltringham urges for a study of law as a social and “flawed human process” (p. 23)–one that is shaped by the complex and dynamic actions of people that enact the law rather than by a simplified and detached code of legal conduct. In doing so, he skilfully resituates the ICTR as an institution that has a life beyond the documents that produced it.

As ironic a conclusion as it may seem for a book whose call is to move away from a textual study of law, in essence, Eltringham’s major focus in this book is on narrative constructions. This is evident in his analysis on two levels: narratives put forth by and about the ICTR as well as narratives about legal practice. As Eltringham tactfully demonstrates, the ICTR is made up of a multiplicity of legal actors (lawyers, judges, and administrative officials, among others), each with their own, at times contradictory, version of what the tribunal did and achieved. The diverging opinions about the tribunal’s status vis-à-vis truth commissions is prime example of this. Therefore, by actively engaging with these narratives, Eltringham approaches the ICTR not as a “disembodied, abstract ‘super-person’” but as “a collection of situated persons” (p. 19). In this vein, one can also read Genocide Never Sleeps as a scholar’s intervention into the narrative construction of the ICTR’s work and legacy, challenging the idea that the tribunal’s archive (court transcripts) along with its legal actors (primarily lawyers and judges) are the only ones entitled to recount the ICTR’s history. This is particularly evident in Eltringham’s scrutiny of legal practitioners’ accounts of allegedly problematic witness testimonies touted as symptomatic of “Rwandan culture.” To counter this claim, Eltringham carefully analyses lawyers’ and judges’ thoughts on and various moments from witness testimonies (such as misunderstandings that may be caused by lack of contextual knowledge and distort intent if left unaddressed (p. 128) as well as underscoring the dialogical nature of these testimonies. In doing so, he demonstrates that the impediment to the production of “conventional” witness statements may be the result of the constraints posed by legal culture rather than the culture of a particular people (p. 151).

By focusing on the people, rather than the rules and regulations, that bring law to life, Eltringham urges for a study of law as a social and “flawed human process” (p. 23).

As seen above, narratives about what the ICTR did and achieved are deeply entangled with narratives of legal practice. These narratives are also interrelated with the perpetual tension between legal text and legal action. In Genocide Never Sleeps, this tension can be observed in multiple instances, especially since the improvised nature of the ICTR, along with its international, multilingual environment, turned the proceedings, and hence the legal procedures that underlie them, into a constant work in progress. Eltringham demonstrates this through the ICTR’s Rules of Procedure and Evidence (RPE). Amended on a continual basis through an annual plenary session, the RPE provided legal practitioners with a supposedly “static, autonomous and authorless” referent (the ICTR acting “independently of human volition” (p. 18)). In reality, it was, of course, a rather direct response to the challenges of courtroom practice, “accomplished by the (re)constructive work of the judges themselves” (p. 115). Likewise, Eltringham’s discussion of LiveNote, the transcription management software that immediately made available witness testimony on lawyers’ and judges’ laptops (which was then used to produce “witness summaries” used in the judgement), is a case in point for the recurring prioritization of legal text over legal action, or purported stability over theatricality (p. 82). On the other hand, the direct challenge posed to courtroom practice by the presence of simultaneous interpretation is an interesting contrast to the above examples. Supposedly neutral bystanders of the trials (unrecognised even in court transcripts or case minutes), interpreters actively contributed to trial content through the censoring of witness testimony they deemed sensitive and interrupting lawyers with technical warnings (about pace and procedure). The lawyers’ frustrated statements about how simplifying their language choice for the sake of interpretation makes it “difficult to control the courtroom” (p. 93) hints at a loss of narrative control in shaping the trial–a sense of control that the RPE and LiveNote both provided.

The lawyers’ frustrated statements about how simplifying their language choice for the sake of interpretation makes it “difficult to control the courtroom” (p. 93) hints at a loss of narrative control in shaping the trial.

There is no doubt, as the above analysis shows, that Eltringham’s account of the ICTR successfully provides “thick descriptions” of the day-to-day workings of the tribunal and superbly demonstrates what it takes to make international law work. I do think, however, that a wholesome view of the individual characters of legal actors (usually heard through snippets of interviews as “a defence lawyer” or “a judge”) is palpably absent in this account. Given that the book’s unsettingly apt title, for instance, is based on an after-hours conversation that Eltringham witnessed between two ICTR lawyers, I was left with a desire to learn more about who these legal actors were beyond their identities in the trial chamber. What did life look like for lawyers and judges, for instance, once a hearing was over? Who was able to enter this legal community of “cosmopolitan locals” (p. 13)? What of those other legal actors (interpreters, stenographers, registry officials, among others) whose voices we do not hear as much as the lawyers and judges? What about the gendered dimensions (noticeably absent from Eltringham’s analysis of the tribunal) of this community and their legal actions? Of course, one can argue that focusing on tribunal dynamics alone through anonymised narratives is an intentional methodological choice (resulting, perhaps, from priority preference of research sites, protection of individuals, or lack of in-depth access). Nevertheless, given the book’s emphasis on seeing law as a social process, providing a more thorough discussion of the social lives (or lack thereof) of the people who made law happen would not only have bolstered the book’s core argument, but also contributed to methodological debates on legal research in anthropology and beyond.

I was left with a desire to learn more about who these legal actors were beyond their identities in the trial chamber (….) Given the book’s emphasis on seeing law as a social process, providing a more thorough discussion of the social lives (or lack thereof) of the people who made law happen would not only have bolstered the book’s core argument, but also contributed to methodological debates on legal research in anthropology and beyond.

This absence, however, does not take away from the unique insights provided by Genocide Never Sleeps, one of which is Eltringham’s great success in demonstrating that law is as much about human intervention and improvisation (especially in the unique context of the ICTR) as it is about procedures and regulations. Ground rules still undergird the hearings, but Eltringham exposes the intricate ways in which they get questioned, bent and quite literally negotiated amongst the various actors that bring law to life. Eltringham’s observations about the exceptional case of the ICTR also provide fertile ground to further assess the everyday legal practices normalised and taken for granted in domestic contexts (p. 25). Furthermore, by putting legal actors, rather than texts or files, front and centre, Eltringham also draws much-needed attention to the affective components of international criminal law (emotional and psychological toll of the trials; boredom endured in hearings; frustration experienced over technical details and expectations). By attending to the minute and often invisible components of legal practice, Eltringham underscores the need for and value of focusing on process (messy and intangible) as opposed to merely outcome (sterile and quantifiable) in order to better assess the workings of international criminal law. Overall, in full reverence to the old anthropological adage of making the familiar strange, Eltringham does a superb job of turning the site of international tribunals into an unfamiliar new terrain with fascinating insights to debate for anthropologists and legal scholars alike.

Eltringham, N. (2019). Genocide Never Sleeps: Living Law at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108757195

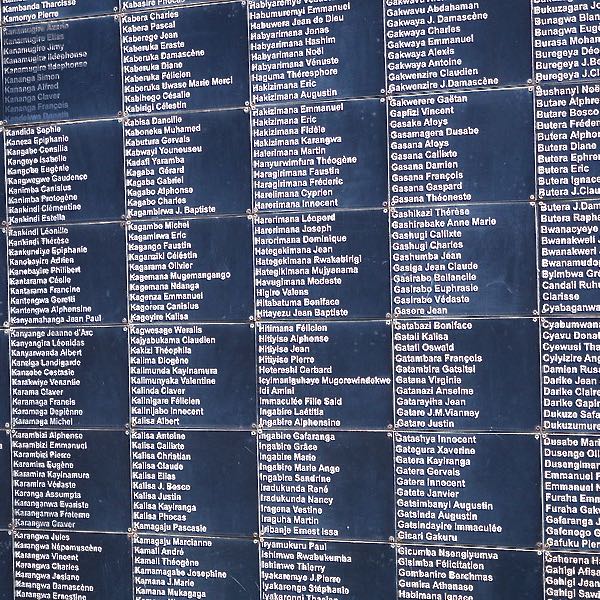

Featured Image: Kigali Genocide Memorial Wall of Names. Photo (cropped) by Laurent de Walick, Flickr (CC BY 2.0)