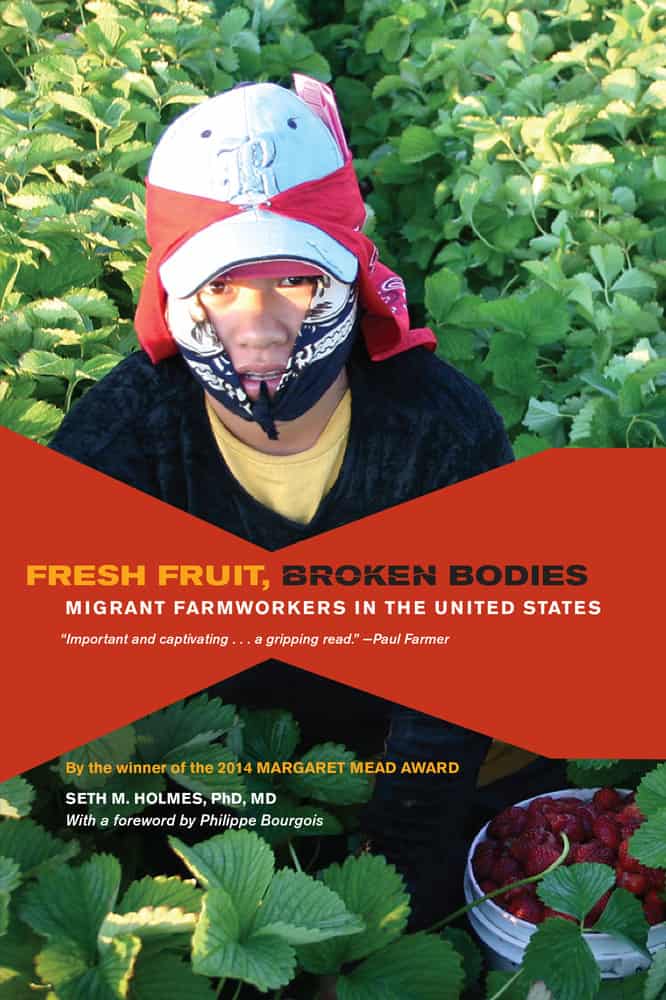

Seth Holmes’ ethnography Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies is a timely and innovative text blending theory and praxis. As a physician anthropologist, the author tries to better understand the socio-cultural and political economic factors shaping the conditions in which Indigenous Oaxacan migrants live, labour, suffer, and treat their physical ailments.

Holmes guides the reader through this endeavor by providing an intense blend of informant life histories, their clinical case studies, observations of and conversations with additional social actors on the farms and in the clinics he visited.

He augments his empirical findings with reflexive social analysis regarding his positionality in studying migrants’ experiences in the “violence continuum” (p.90) – the structural-symbolic processes that materialise Triqui and Mixtec migrants’ pain and suffering as they engage in agricultural work and cross-border movement.

Holmes takes us along the Triqui migrant trail as he follows his compadre, Macario, from Mexico to Arizona to California. If Bourgois’s foreword does not spark intrigue, readers find an intensely captivating introduction detailing how Holmes and nine of his Triqui companions trekked across the Sonoran Desert and were subsequently captured and deported (or in Holmes’ case, released, but cited and fined). He critically presents his encounter with United States Customs and Border Protection to show how he and his informants experience the border differently because of their differently coloured and situated bodies; he saliently teases out the intersections of race and class as hierarchies are reproduced before, during and after informally crossing the border. These hierarchies follow the Triqui migrants into the fields around the farm and into the patient rooms in clinics whilst they remain relatively hidden from public view. Migrants live in housing camps provided by the farm near the “multi-level houses of the upper class that have picturesque views of the valley” or in “squatter shacks made of cardboard, plastic sheets and broken-down cars” that are in sub-par living conditions (p.47). This is a layout that reflects the way Anglo farmers, secretaries, clinicians and even U.S. Latina/o workers view Indigenous Oaxacans: as not really Mexican because they don’t speak Spanish and are ‘more dirty’ or ‘less respectful,’ as one Anglo administrative assistant relayed to Holmes on the farm (p.67).

Holmes takes us along the Triqui migrant trail as he follows his compadre, Macario, from Mexico to Arizona to California. If Bourgois’s foreword does not spark intrigue, readers find an intensely captivating introduction detailing how Holmes and nine of his Triqui companions trekked across the Sonoran Desert and were subsequently captured and deported (or in Holmes’ case, released, but cited and fined). He critically presents his encounter with United States Customs and Border Protection to show how he and his informants experience the border differently because of their differently coloured and situated bodies; he saliently teases out the intersections of race and class as hierarchies are reproduced before, during and after informally crossing the border. These hierarchies follow the Triqui migrants into the fields around the farm and into the patient rooms in clinics whilst they remain relatively hidden from public view. Migrants live in housing camps provided by the farm near the “multi-level houses of the upper class that have picturesque views of the valley” or in “squatter shacks made of cardboard, plastic sheets and broken-down cars” that are in sub-par living conditions (p.47). This is a layout that reflects the way Anglo farmers, secretaries, clinicians and even U.S. Latina/o workers view Indigenous Oaxacans: as not really Mexican because they don’t speak Spanish and are ‘more dirty’ or ‘less respectful,’ as one Anglo administrative assistant relayed to Holmes on the farm (p.67).

In the second chapter, Holmes explains how farmwork in the U.S. today cannot exist without violence structurally and symbolically directed at migrant workers.

It is the anthropologist’s duty to experience the border through his body, to suffer the border as the people-turned-migrants-turned-informants do, to better understand what they endure. But even as he tried to experience the suffering of his informants through multi-sited ethnography, he is always pushed back to his social position as an educated, white man enjoying more dignity and respect than his migrant farmworker informants. As Holmes eloquently states, “Structural violence – with its pernicious effects on health and symbolic violence – with its subtle naturalization of inequalities on the farm, in the clinic, and in the media – form the nexus of violence and suffering through which the phenomenon of migrant labor in North America is produced” (p.44). During his fieldwork, Holmes suffered knee, back and neck aches among other pains as his informants did, but admitted to using a “local private gym to ease the aches, all too aware of the inequality of having access to such amenities” (p.88). Migrants he interviewed expressed their numbness to pain in certain areas, whilst yet others expressed that they hurt all over since they started laboring (p.89). The salient juxtapositions of his bodily experiences to those of his Triqui and Mixtec interlocutors, once again, serve as a reminder of how differently positioned – racially and socio-economically – they are to one another.

Chapter three especially resonated with my own experience. Holmes’ analysis of “the ethnic-labor hierarchy” (p.81) at work on farms in Washington and California, briefly referenced above, reminded me of how one summer, in 2013, I visited my Mexican American relatives in Michigan, some of whom work as crewbosses (supervisors) or pickers in various Anglo-owned berry farms. I went to work on a raspberry and blueberry farm, which also served as a U-Pick market, after my uncle, a supervisor, said he could recruit to make extra cash for my bus ticket back to Texas. I laboured on the farm for two weeks and made between 60-70 dollars a day (not including weekends), depending on what time we left. On one of these days, before noon, I was bent over pruning the bushes – a sweet blood red stained my khaki pants. An Anglo family stopped by, to pick their own berries, after a well-off Latino family had already left. The farmer, a stocky, bald fellow with shades, instructed them to pick in the sections that were already pruned. A few seconds after his suggestions, they walked over to where I was on my knees, my stomach parallel to the ground as I pruned the outgrowth. The family, including an elderly woman, picked raspberries only a few bushes away from me. They looked down at me as they picked, moving bush to bush, stopping every few seconds to gaze at me on my knees. I felt humiliated, but kept pruning with dignity.

Ethnic segregations at work on farms anywhere extend beyond worker relations, and are reinforced in instances such as the one I experienced, when members from the larger community behave in ways that reproduce ethnic hierarchies between themselves and workers as the former self-pick their fresh fruit.

Holmes’ last chapters are necessary empirical forays into the quotidian times and spaces in which symbolic violence and bodily suffering are normalised, naturalised and reinforced in the various contexts in which migrants live through on both sides of the hyper-militarised U.S.-Mexico border. Chapter four explores his compadres’ narratives of illness and shows how, for example, Bernardo’s stomach ache is rooted in deeper “social and political forces” (p.107); chapter five builds on these narratives of pain and torture, which travel with them across borders, to reveal how healthcare professionals understand migrant health and treat migrants’ illnesses through their own naturalised notions of rigid ethnic and class differences. It is in the conclusion that Holmes shifts gears and proposes scholars and health professionals embark on embodied reflexive approaches to better understand the conditions in which we live our unequal lives, usually taken as givens. He shows that even when efforts are declared for solidarity or improvement of living conditions for migrants on the farm, they do not always last or follow through because of the decision made by those in power on the farms and in the clinics, as well as at the international policy level.

The road to “pragmatic solidarity” (p.190) on the farm seems out of reach when confronted with the nightmarish everyday violences that migrant laborers continually endure.

Holmes leaves readers with a critical and daring question, asking: “How would the role of health care professionals look if we took seriously our call to relieve and prevent suffering while also remembering the structural forces fundamentally producing the suffering?” (p.193). Practical solutions to such global inequalities, he proposes, can be reached not so much through textual and visual representations, but through broad coalitions aimed at dismantling hegemonic neoliberal regimes that promote violence and suffering unto populations on both sides of the border.

Holmes, Seth. 2013. Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. Oakland: University of California Press. 264 pp. Pb: $29.95. ISBN: 9780520275140

Featured image by Alex Proimos (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)