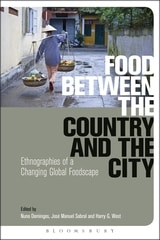

I welcomed the opportunity to see how scholars of food studies would make use of one of my take-to-the-desert-island favorite books, Raymond Williams’The Country and the City. Williams encouraged us to view cultural productions as integral to political economies and their attendant imaginary geographies and temporalities. The Country and the City probed literature to elucidate enduring tropes of the country as a timeless site of past tradition versus the city as the fast paced site of the future. The editors of this current volume extend Williams’ insights into tropes of the country and the city to the problem of food in the contemporary era, featuring the industrialisation of food production and transformations in infrastructures affecting the potential circulations of both peoples and food. The essays examine the complexities of these tropes as they appear in contemporary food literatures, including cookbooks, advertisements, tourist guides, novels, memoirs, and less riveting, although necessary, food policy publications. As the editors’ note in their introduction, the terms ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ in contemporary food discourses are either used (consumed?) uncritically in the folk categories of everyday speech, or strategically in the case of promotional materials for food commodities. However, in food studies, we need to consider them as part of our object of study in order to comprehend their role in the varied “lived experience” of food.

The authors in this volume treat us to several fascinating examples of the tenacity of these tropes in the messy and dynamic material realities of contemporary food production, circulation, and consumption.

These longstanding tropes of country and city are sometimes idealising and sometimes denigrating. Zubaida’s paper reminds us that the condescending attitude of city Folks about the food of country folks is not limited to Europeans. Karl Marx’s famous “idiocy of rural life” comment is given a full equivalent in the sardonic and witty critique of 17th century Yusuf al-Shirbini, who issues his searing commentary about the food preparation of the rural peasants of the Nile from his perspective as an urbanite Egyptian Ottoman. Abbotts describes how the folkloric figure of the chola in the Ecuadorian Andes serves as a mediator between the country and the city. Adorned in her distinctive hat and skirt, she is the indigenous purveyor of rural foods in cities where people understand themselves as European, modern, and advanced. Cholas are revered as icons of rural purity, but when they adopt city fashions and ways, they are perceived as polluting the white ideological space of cities. Food and fashion is also present in Hull’s paper. In South Africa, food practices are central to reworking the opposition between tradition-rural-production and modern culture-urban-consumption in contemporary post-apartheid South African society as the locales of cultural innovation and consumption shift. Pottier discusses the engagement of anthropologists from Godfrey Wilson to the Manchester School in the ‘rural-urban modernisation’ myth in Africa, so criticised by James Ferguson. In contemporary Malawi, no seamless transition takes places as hunger and poverty require the continuing coproduction of urban and rural kin. Wealthy America has seen the emergence of food ‘deserts’ as large grocery stores disappear in stark urban decay in post-industrial cities like Detroit. Urban agriculture seems to pose a hopeful glimmer of a productive revitalisation. However, DeLind, the self-critical academic and urban gardener in East Lansing, Michigan, cautions that the seemingly benign community gardens, touted by neoliberal reformers, can appear as a ‘wolf in green clothing’ (p. 102), eroding the sociality of poorer, black urban neighborhoods as they take over its space.

For homesick migrants in Lisbon, it does not matter if the food they eat is produced in the city or the country as long as it is the food of the homeland, Guinea-Bissau. Foreign (European) food is thought to trigger “corporeal adversities and cosmologic insecurities” (p. 132). Ironically, it is European scientific discourses that validate their beliefs about the superior, healthful qualities of their own foods such as African eggplants and baobab leaves. Bulgarian scientists in the Soviet era studied the health qualities of the lactic bacteria of yogurt, as evidenced by the longevity of the rural peasants, arguing that yogurt should be an essential food for the urban proletariat. It also became a valuable food commodity for export. Introduced to Japan at the Expo ’70 world fair in Osaka, Bulgarian yogurt became a health product for Japanese consumers. With ads featuring sumo wrestlers describing Bulgarian yogurt as a gift from heaven, the Japanese firm Meiji promoted images of bucolic Bulgaria as a ‘holy land of yogurt’, which in turn affected how yogurt is understood as a national symbol for post socialist Bulgarians.

From the countercultural movements of the Sixties to the more recent Slow Food movement, food has been central to resisting capitalism’s globalising, homogenous trends.

However, Sobral notes there is a danger that foods of the ‘traditional’ Portuguese countryside may become a ‘frozen’ corpus of written recipes (p. 158) in such appropriations of food-as-culture. Nonetheless, individual memories of the countryside’s food lend persuasiveness to Portugal’s contemporary imagined national community. ‘Tradition’ often marks imaginary spheres of lost country foods in dire need of reclamation in ‘new pastoral’ imaginings in Portugal. Domingos discusses the creation of sub-regions of ‘certified quality’ of wine production in the Alentejo region of Portugal. The large producers of successful regional wines are not necessarily local, but images of ‘wild’ and ‘authentic’ rural localities, and faceless peasant women in traditional clothing, are present on their wine labels and in their promotional materials. The featureless faces of the rural women represent the erasure of rural laborers and their pains, fears, and poverty. This ‘habitus’ is excluded from this new pastoral as is the history of serfdom in contemporary country/city narratives in Portugal.

West offers a perceptive engagement not only with Williams’ theories and the contemporary EU regulations that govern food production and circulation, but also with staid anthropological concerns of kinship, inheritance and residence patterns, which prove, perhaps surprisingly, their continuing relevance. His rich ethnography demonstrates how French farmers actively engage with tropes of locale and their attendant assumptions about production and consumption. The Bellonte family, producers of Saint Nectaire cheese in the Auvergne region of France, do not timelessly reproduce an ancient cheese in an untouched rural idyll; like the tradition of which it is a part, cheese is a living entity. The need to adhere to EU hygiene standards requiring nonporous storage containers mean that the ancient volcanic caves of the region can no longer be used for ageing cheese. At various historical moments what these caves housed – saints’ bones, renegade priests, wine cellars, and sheepfolds – are now showcased in the small museum that has been constructed in the caves. This museum, along with tours of the farm, restaurants, and a shop selling regional food products, mean that the Auvergne countryside becomes a site of consumption. Rather than a ‘Disneyfication’ of rural heritage, these practices allow the Bellonte family to resist the postwar trend of rural influx into urban factory jobs. Further, setting aside a traditional stem family form of kinship where one child inherited the family land, the Bellonte family chose to transform their land into an EU supported family farm enterprise (p. 87), so that all the children, their spouses and progeny, are able to make a viable living on the farm.

The Mediterranean Diet made the list of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010. It is often presented as a timeless, positive diet leading to longevity, as Truninger and Freire note in their essay. More popular in Northern than Southern Europe, it is advocated by nutritionists and health professionals as a rural diet that holds the solution to the health problems that plague the ‘modern’ urban people. Olive oil as the premier fat, as opposed to animal fat, is key to the argument about why the Mediterranean Diet was so healthy. The authors challenge us to consider how the ‘Mediterranean Diet’ is an urban oriented ideological creation that can be questioned by historical research. For instance, they reveal that the rural folk who ate the ‘Mediterranean Diet’ in the 1940s said, off the record, that they had been hungry and longed for meat. Another element of the imagined Mediterranean Diet asserts patterns of sociality: it proposes that people ate lengthy meals at regular times together, which poor Mediterranean people were rarely able to do as food production is laborious, time consuming and sometimes isolating.

The Mediterranean Diet made the list of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010. It is often presented as a timeless, positive diet leading to longevity, as Truninger and Freire note in their essay. More popular in Northern than Southern Europe, it is advocated by nutritionists and health professionals as a rural diet that holds the solution to the health problems that plague the ‘modern’ urban people. Olive oil as the premier fat, as opposed to animal fat, is key to the argument about why the Mediterranean Diet was so healthy. The authors challenge us to consider how the ‘Mediterranean Diet’ is an urban oriented ideological creation that can be questioned by historical research. For instance, they reveal that the rural folk who ate the ‘Mediterranean Diet’ in the 1940s said, off the record, that they had been hungry and longed for meat. Another element of the imagined Mediterranean Diet asserts patterns of sociality: it proposes that people ate lengthy meals at regular times together, which poor Mediterranean people were rarely able to do as food production is laborious, time consuming and sometimes isolating.

The tropes of country and city, myths functioning as memories, as Williams understood them, have not gone away. It is our role as anthropologists of food to understand how they continue to operate in our era where food is central to imagined nations, shaped by international standards, capitalist food enterprises, and voluntary and involuntary migrations of people.

This volume helps us think through how people who need to eat to live, and aspire to do so in a meaningful way, are both enabled and constrained in this endeavour.

Domingos, Nuno Miguel, Sobral, Jose Manuel and West, Harry G. (eds.). 2014. Food Between the Country and the City: Ethnographies of a Changing Global Foodscape. London: Bloomsbury Academic. 264 pp. Pb: £22.49. ISBN: 9780857855381