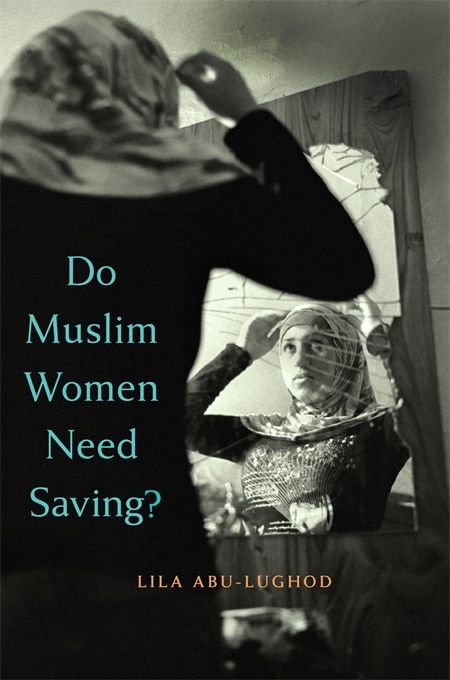

Lila Abu-Lughod’s book, Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, expands on her thoughts from an earlier article similarly titled. As she explains, this book is “a long answer to the question of whether Muslim women have rights or need saving” (p.201). Her overarching theme is that although there is no doubt that some women may need help, the manner in which the West looks upon these women and aims to ‘save’ them reduces the agency of the women to whom they claim to offer help. Abu-Lughod examines a number of points to illustrate her stance. Her chapters look at publications on Muslim women, both popular ‘non-fiction’ biographies, as well as books on the importance and necessity of saving women, such as Kristof and WuDunn’s Half the Sky. Through these books Abu-Lughod is able to talk about the conception of Islamland (the homogenisation and essentialisation of Islam and Muslims everywhere) as well as gendered Orientalism and the authorising of moral crusades (one of her chapter titles). In the second half of the book she looks at the West’s obsession with honour crime, and the place of anthropologists in the field of human rights and women’s rights in particular today.

She starts by looking at America’s recent use of images of Afghan women in burqas in the campaign to build up support for the War in Afghanistan. She illustrates that the simple image of a woman, or rather a Muslim woman in a veil, coveys the Orientalist assumption of oppression and a need to be saved. Highlighting the political nature of these images, she explores the ideas of Orientalism and the colonial approaches that still mar the representation of Muslim women. From this starting point, Abu-Lughod is able to move on to critique the recent proliferation of books focusing on the lives and treatment of Muslim women (which she calls ‘pulp-fiction’). This topic has been explored by authors such as Milani (2008) and Sensoy and Marshall (2011) who similarly conclude that not only does this work facilitate the spreadof Orientalist views of Muslim women, but it also implies that all Muslim women need and want to be saved by the West. These books thus share similar features: Muslim women being abused, their attempt to escape (for Western ideals) and the fact that they are all ‘true’.

She starts by looking at America’s recent use of images of Afghan women in burqas in the campaign to build up support for the War in Afghanistan. She illustrates that the simple image of a woman, or rather a Muslim woman in a veil, coveys the Orientalist assumption of oppression and a need to be saved. Highlighting the political nature of these images, she explores the ideas of Orientalism and the colonial approaches that still mar the representation of Muslim women. From this starting point, Abu-Lughod is able to move on to critique the recent proliferation of books focusing on the lives and treatment of Muslim women (which she calls ‘pulp-fiction’). This topic has been explored by authors such as Milani (2008) and Sensoy and Marshall (2011) who similarly conclude that not only does this work facilitate the spreadof Orientalist views of Muslim women, but it also implies that all Muslim women need and want to be saved by the West. These books thus share similar features: Muslim women being abused, their attempt to escape (for Western ideals) and the fact that they are all ‘true’.

Abu-Lughod understands such texts as perpetuating homogenising and Orientalist concepts of Muslim women, and examines why there is an enduring and disturbing obsession with these types of works in the West.

While Abu-Lughod investigates the spread of pulp-fiction books, she also looks at other texts, including Half the Sky, that call for Western feminists to take on the quest of saving women worldwide. Whilst she accepts that there are indeed women in need of help in the developing world, she points out that the focus of these authors takes away from issues within their own countries: America is ostensibly ‘free’, yet still plays host to violence, spousal abuse, and other forms of crime that are often ignored in these kinds of work. Rather, they focus on the need to save these unfortunate women who (rightly or wrongly) cannot save themselves. In this section she disturbingly brings the reader’s own assumptions and beliefs into question by exploring the work of those whom some would call pious, who only aim to help. However, she postulates that in truth they only replicate unnecessary and damaging stereotypes. As someone who has read Half the Sky, I feel that her point is both valid and necessary, but one cannot help but question that if all publications and work on the women and children of other civilisations is part of a gender Orientalist perspective, should we even continue to donate and support charities? Where is the conceptual line drawn between being aware of and challenging the issues and vetoing the whole discourse? This, of course, is a problem faced by many development anthropologists (e.g. Escobar, Mosse and Porter).

Working within the framework of rights as an anthropologist and supported by her previous professional experience, Abu-Lughod thus exposes the problems that she feels lie within the discourse.

Like many others before her, she questions the place of anthropologists within the discourse – should they take a militant approach like Scheper-Hughes, or be more wary? For Abu-Lughod this wariness stems from her own experience with the ‘real’ women of Islam, and her knowledge that one woman’s problem is not the same as her neighbour’s, her country’s, or all Muslim women. In this section, Abu-Lughod introduces Islamic groups that explore women’s rights and is careful to remind the reader that she does not mean to discount the useful and positive work of activists, but rather highlight the considerations that must be made by anthropologists exploring rights and issues within the discourse.

In questioning these aspects she uses her own experience, fieldwork and understanding of Muslim women today. As she points out in her very first page, it’s not that these women are not oppressed, or do not see themselves as not being oppressed, but rather that they do not see it as being the fault of Islam as the West tends to assume. It is therefore not the question of ‘do women need saving’ but rather ‘do Muslim women need saving’ and the accompanying attitudes that Abu-Lughod draws attention to. Instead, she wants readers to look at these women as real people, and ask them what they think, want and hope for, rather than making assumptions on their behalf. When we challenge this assumption, we challenge ingrained ideals that are not necessarily valid or worthy. Abu-Lughod thus forces us to look at our assumptions and the cost that such views may have for the recipients of our attention. Her work is not flawless and the chapters encompass a lot of different topics that seem only just connected through Orientalism. Whilst a more thorough exploration of Orientalism, and gendered Orientalism in particular, would have been useful, her argument is compelling, interesting and very relevant to the world today.

References

Kristof, Nicholas D. and WuDunn, Sheryl. 2010. Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Milani, Farzaneh. 2008. On Women’s Captivity in the Islamic World. Middle East Report, 246, pp. 40–46.

Sensoy, Özlem and Marshall, Elizabeth. 2011. Missionary girl power: saving the ‘Third World’ one girl at a time. Gender and Education, Vol 22(3), pp. 295–311.

Abu-Iughod, Lila. 2013. Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Harvard: Harvard University Press. Pp. 336. HB $35. ISBN 9780674725164.

An impressive share! I have just forwarded this onto a friend who had been doing a little research on this. And he in fact ordered me breakfast because I stumbled upon it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending some time to talk about this issue here on your website.