In 1978, psychologist Jack Flasher defined the term ‘adultism’ as a way of perceiving children “not only as unconditionally subordinate until they attain legal adulthood but also, as inferior […] from adults. The misuse of powers may take the form of overly protecting a child. Adults tend to see children in general as less capable than they are in actuality or could be if this bias did not exist” (p.517). In this sense, many scholars – including anthropologists – have criticised the adultcentrism that exists in contemporary societies. Children of Afghanistan represents an attempt to give importance to childhood in Afghanistan (and, by extension, childhood in the world in general) by putting “children at the forefront of the conversation” (p.1).

The overarching theme of the book is that childhood is the most vulnerable stage of life and should to be protected and taken into account when discussing related issues.

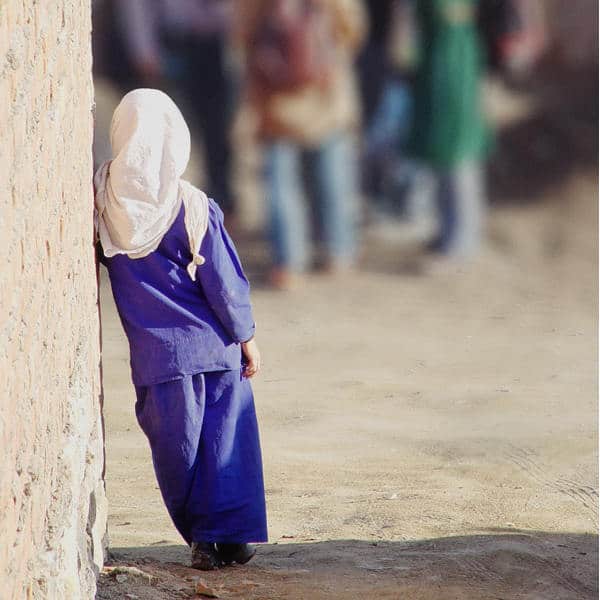

The 1979 war in Afghanistan profoundly affected the lives of many people. As showed by Amina Kator-Mubarez in Chapter 1, although a variety of different experiences exist within childhood and youth before and after 1979, inequality and disparity still persist. As Anne E. Brodsky notes in Chapter 2, entitled Narratives of Afghan Childhood, the war also influenced the perception of childhood. Karen Dubinsky (2007), who writes about the real and symbolic power of childhood, invites us to think over the diversity of social significances of childhood throughout history and within different societies; childhood is considered by many anthropologists as an indicator of national and racial identity. In the same way, in her analysis of the representation of children in film, Teresa Cutler-Broyles shows children as a symbol of the Afghan society and as liminal figures in the shadows, represented as present or past but never actually present (p.69).

The 1979 war in Afghanistan profoundly affected the lives of many people. As showed by Amina Kator-Mubarez in Chapter 1, although a variety of different experiences exist within childhood and youth before and after 1979, inequality and disparity still persist. As Anne E. Brodsky notes in Chapter 2, entitled Narratives of Afghan Childhood, the war also influenced the perception of childhood. Karen Dubinsky (2007), who writes about the real and symbolic power of childhood, invites us to think over the diversity of social significances of childhood throughout history and within different societies; childhood is considered by many anthropologists as an indicator of national and racial identity. In the same way, in her analysis of the representation of children in film, Teresa Cutler-Broyles shows children as a symbol of the Afghan society and as liminal figures in the shadows, represented as present or past but never actually present (p.69).

Children have to be protected from violence, child marriage, sexual exploitation and all forms of threats that increase their vulnerability.

In addition, their basic needs such as health necessities and education should be guaranteed universally. Although the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child aims at ensuring the best interests of children, its application is limited. In the case of Afghanistan, as Hangama Anwari writes in Chapter 10, a clear legal protection framework is needed.

Perhaps one of the main controversies refers to the legitimacy of violence to children in communities. In Love, Fear and Discipline in Afghan families (Chapter 4) Deborah J. Smith points out that there is a contradiction between the ideal and reality. There are three main categories of community discourses regarding acceptability of punishment: corporal punishment as a last resort; corporal punishment as altogether acceptable; and all forms of violence to children as unacceptable (p.89). However, in practice, corporal punishment is accepted as ‘normal’ and violence is a form of discipline and punishment. The principal justification given is that parents are worried about the future of their children. In Smith’s view, this reasoning is weak and she defends the need to change the attitude to considerations of violence to children as being “not only as unacceptable, but also as dishonourable and something to be avoided at all costs, something that is not tolerated by the community” (p.91). Smith also notes that the “key to understanding violence to children in the family is conceptualizing the difference between violence being accepted versus being perceived as acceptable” (p.92).

Another concern has to do with child exploitation in terms of child labour, child marriage, and child soldering. Child labour in particular has a notable presence in Afghanistan. Amanda Sim’s chapter, Confronting Child Labour, highlights the views of Afghan families and evidences the importance of bearing in mind the emic perspective. Though poverty is a contextual factor, the way households weigh the costs and benefits of school and their differing perceptions of risk are factors that influence the decision to send children to work outside the household (p.127); child labour is thus a strategy to keep children safe and out of trouble (p.132). Child labour also highlights community gender norms, as boys can be sent outside of the household while girls work in the household due to perceptions of “their presence in the public sphere [as being harmful] to family reputation and honor” (p.132).

Similarly, child marriage is considered a way of protection since the 1979 war, according to Sharifa Sharif in Chapter 6. The conflict increased vulnerability within society, and the practice can be understood as a social strategy that strengthens the bonds and wealth of a family.

As Delphine Boutin writes in Chapter 9, Child Soldiering in Afghanistan, the use of children in armed conflicts is often due to a lack of employment and education opportunities. Moreover, participating in armed groups can be “a way for children to honour their ideological beliefs and political opinions. In a country where martyrdom has deep cultural roots and is often glorified, children may learn to feel the willingness to die for a noble and just cause” (p.156-157). Boutin, however, fails to find exhaustive reasons for why children join armed groups due to the complex nature of the phenomenon.

Finally, although little is known about other forms of exploitation such as sex work or drug trafficking due to their taboo nature in Afghan society, Boutin asserts that we should identify and respond to such cases in order to obtain more information and raise awareness. However, what is clear is that there are contradictions between what is established in law and the reality of the situation ‘on the ground’. The main problem is the lack of central laws prohibiting such practices that damage the rights of children. As Hangama Anwari concludes, the “protection of children should be integrated into all national planning processes” (p.180).

In terms of health, Steven Solter offers hope in his chapter Children’s Health (Chapter 11). Despite high rates of child mortality, the situation has been improving since 2002. Different strategies such as vaccination, the training of community health workers and midwives alongside other activities have contributed to a marked improvement. Similarly, Fitsum Asefa, Annalies Borell and Charlotte Dufour affirm in Chapter 12 that despite the support received from international organisations, children still suffer from undernutrition due to “the lack of high-quality food, a high prevalence of infectious diseases, and the significant challenges that families face in providing adequate care for infants and young children” (p.198). These challenges can be more arduous when children have disabilities because, as Lael Adams Mohib writes in Chapter 13, often the best scenario for these children is basic care given at home from family members who do not have any training or external support (p.213). The reality of children with disabilities is hidden from the public eye and is thus effectively unknown.

Children of Afghanistan is also concerned with the role of education, a key child right, as a way of obtaining opportunities in an uncertain future and a tried and tested path to peace (p.16). Omar Qargha indicates that, after four decades of conflict, neither Afghan children nor the refugees who returned to Afghanistan have experienced security or peace in their homeland (p.241-255). Mamiko Saito’s respondents describe their experience of ‘returning’ as a “mix of stresses and emotional struggles” (p.241). Although she makes a great contribution in terms of educational issues, the conflicts of identities between young refugees and their sense of belonging in relation to ‘others’ must also be considered. Alterity and otherness are of anthropological interest and it becomes particularly remarkable “in the context of forced displacement and the effect of having legal status different from that of the citizens of the host country: the ‘other’ is not only a member of one’s own family, kin, or other linguistic or ethnic group, but also a ‘national other’” (p.242). For this reason, the ‘returning’ can produce a sense of alienation in young refugees.

The book also deals with the necessity of empowering children and young people. Teenagers in Afghanistan use mass media and social networks to fight the corruption, repression and corrosion of the ‘fake’ democratic Afghan state. Clearly, it evidences the role of children and youth in Afghan society.

In sum, this book is worth reading because it makes clear that childhood represents the future of societies and highlights the need to challenge the adultocentric view. When discussing childhood issues, it is essential that donors, advocates and law makers consider the real necessities of childhood and work for the improvement of their quality of life.

References:

Dubinsky, Karen. 2007. Babies without Borders: Rescue, Kidnap and Symbolic Child. Journal of Women’s History, 19(1), 142-150.

Flasher, Jack. 1978. Adultism. Adolescence, 13(51), 517-524.

**************

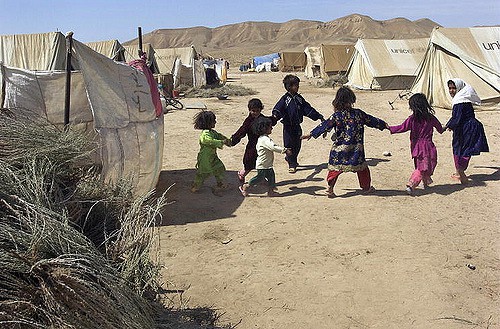

Featured photo by Giant Humanitarian Robot (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)