In September 2015, an image of a three year old Syrian child, lying lifeless on a Turkish beach, travelled the world in a matter of hours. In tragic irony, his picture transcended borders that the little boy himself would never have a chance to, as he (and countless others) sought safety within the boundaries of the EU. The image provoked a collective and visceral response, challenging taken-for-granted social constructions of childhood, and evoking a stark recognition of children’s engagements and at times violent confrontations with borders. Indeed, in partial response to this, Germany’s borders were unequivocally (though in the end temporarily) opened to receive refugees fleeing the Syrian conflict. The social positioning of the child in relation to the border, and the ways in which children interact with, transform, and are themselves altered by their encounters with borders, even in death, are distinctly manifest here.

Childhoods and borders are profoundly interweaved, as part of the social processes which give rise to, maintain, challenge, and transform symbolic boundaries, be they institutionalised or not.

Yet to date, there has been limited attention granted to this disciplinary intersection within critical sociological and anthropological thought, and it is this lacuna that Spyrou and Christou make initial steps towards addressing in Children and Borders.

Borders are often, and indeed predominantly within this publication (though not exclusively), invoked in an institutional sense, as delineating the boundaries of what Anderson (2006: 6) referred to as “an imagined political community.” This is immediately put across in Tran Thi Ha Lan and Huijsman’s opening chapter, which considers how ethnic minority youth experience the state in a Lao-Vietnamese Borderland. The project of state-making, partially enacted through a defining (yet fluid) state line cutting across ethnic boundaries, was encountered by the youth in a gendered and habitual manner, and was brought into play as they explored future aspirations within a marginal and unequal social landscape. However, the state was largely viewed by the youth as an agent of socio-economic process, and not particularly recognised as a physical manifestation at the border. The fluidity of the border rendered it largely insignificant to the youth, who resisted any sense of ‘border experience’. Furthermore, their liminal positioning between the spaces of childhood and adulthood both allowed and shaped their participation in illicit (though community-sanctioned) economic activities, which in turn necessitated daily crossings, cultural performances, and transgressions at the border.

The occupation of this ‘in-between’ space, destabilising the borders between childhood and adulthood, are also considered in other chapters in the collection, including Grinberg’s analysis of representations of Palestinian ‘Children of the Junction’. The physical body of the child here both challenges and demarcates the border in a way that adult bodies cannot, enabling limited and narrowed access to the ‘other side’ for the purposes of earning money through peddling goods, begging, and cleaning windshields. The controlled space at the border itself destabilises the borders of childhood, and is inscribed on the abjectified body of the child, in many ways expelled from childhood and forced into the adult position of provider by the very nature of their malleable working bodies. Locating children within the liminal space between childhood and adulthood is similarly observed in other chapters, including Basu’s chapter on children’s border movement from Bangladesh to India. Basu explores how children are caught between dualisms of citizen and non-citizen, insider and outsider, victim and perpetrator, child and adult, and desirable and undesirable, all within a context of perceived terrorism threats, and subsequent heightened security and enforced segregation. Children apprehended at the border navigate between these continuums, in the process being constructed as both victims at risk, and undesirable perpetrators and deviants.

The construction of what is and is not socially desirable is a theme that presents itself in a number of ethnographic illustrations in the volume, in light of one of the primary functions of symbolic boundaries to protect the integrity of that which is socially desirable, and to keep the abject permanently expelled.

This sense of moral pollution is clearly communicated in Meichsner’s chapter on residential child care along the Mexican-American border, wherein children are constructed as needing to be rescued from the propagation of dangerous and sinful vices which would otherwise plague them. Evoking a symbolic boundary (which is not necessarily or exclusively physical) is crucial to the process of ‘othering’, and may be shifted accordingly in relation to who is being constructed as the socially undesirable other at any given time (Attard 2013). This is similarly observed in McKnight and Leonard’s chapter on young people’s experiences of post-conflict Belfast. Aside from the borders materially etched in to the landscape in the form of ‘peace walls’, symbolically constructed and invisible borders (also evident in Arndt and Tesar’s childhood undergrounds) were also pervasive, reinforcing and normalizing children’s notions of belonging and exclusion.

Akesson’s ethnography on Palestinian children and families likewise argued that borders, as symbols of power, may manifest themselves in both visible and invisible forms, illustrating how Israel’s ‘matrix of control’ (Halper 2000) not only suppresses everyday movement, but also haunts the dreams and aspirations of children in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt). Such borders acted as organising features directing the flow and meaning of everyday life, as young people engaged with social spaces in a way which gave rise to localised notions of identity, and emotional connections to place. Returning to Northern Ireland, this imbued borders with a sense of necessity, despite the constitution of Belfast as a post-conflict city. The notion of borders infused with contested histories and memories is also common to Christou and Spyrou’s work on the Green Line in Cyprus, as children appropriate borders in an exercise of constructing differences, and defining ‘self’ and ‘other’. The boundary itself is imbued with emotional affect, entailing the traversing of an emotional landscape whenever the (recently opened) border is crossed. Ongoing disputes on the nature and purpose of the Green Line, as well as the recent fluidity attached to it, render the boundary both legally and socially ambiguous, giving rise in itself to ambivalent senses of belonging.

Akesson’s ethnography on Palestinian children and families likewise argued that borders, as symbols of power, may manifest themselves in both visible and invisible forms, illustrating how Israel’s ‘matrix of control’ (Halper 2000) not only suppresses everyday movement, but also haunts the dreams and aspirations of children in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt). Such borders acted as organising features directing the flow and meaning of everyday life, as young people engaged with social spaces in a way which gave rise to localised notions of identity, and emotional connections to place. Returning to Northern Ireland, this imbued borders with a sense of necessity, despite the constitution of Belfast as a post-conflict city. The notion of borders infused with contested histories and memories is also common to Christou and Spyrou’s work on the Green Line in Cyprus, as children appropriate borders in an exercise of constructing differences, and defining ‘self’ and ‘other’. The boundary itself is imbued with emotional affect, entailing the traversing of an emotional landscape whenever the (recently opened) border is crossed. Ongoing disputes on the nature and purpose of the Green Line, as well as the recent fluidity attached to it, render the boundary both legally and socially ambiguous, giving rise in itself to ambivalent senses of belonging.

The volume continues to demonstrate how notions of belonging are both reaffirmed and called into question by means of the cultural constructions of borders. Buil and Siegel, as well as Ensor, touch upon this through a consideration of the refugee experience at the border and beyond it, illustrating how refugee’s lives are lived in a state of permanent transition and displacement.

The borderline in itself is live, attributing unequal social value by virtue of its selective permeability, and tinging the everyday life of young people with a lingering sense of marginalisation.

Ensor in particular demonstrates how disenfranchised Sudanese refugee youth in Egypt adopt a fatalistic acceptance of their socially marginalised existence, joining rival gangs that fulfil the purpose of fostering a sense of belonging that their surroundings have otherwise denied them. This is to an extent also observed in Aitken, Swanson, and Kennedy’s chapter, wherein structural violence is seen to fuel individual agency, propelling young people towards exercising social resistance. They thus form their own communities that are bound by shared social transgressions, all the while confronting institutional violence in their own unique and meaningful ways.

Social resistance vis a vis borders may also take on more subtle and muted forms, blurring and challenging understandings of belonging as they are so ascribed by borders (see Kim and Dorner’s chapter, as well as Marques da Silva’s demonstration of continuity beyond the border despite a childhood lived at the periphery). While some children so obscure borders, others still are tasked with internalising them, as with Sedano’s second-generation Dominicans in Spain, whose crossing of the border entails a reaffirmation of belonging to an imagined community of Dominican-ness. Their symbolic membership is strengthened by means of embracing and internalising the border; though in Kutsar, Darmody and Lahesoo’s chapter, such unity (in terms of the family unit in particular) is perceived as potentially threatened through labour migration.

The work outlined within this particular volume provides fertile ground for further interdisciplinary exploration of how children engage with borders. Indeed, encounters between children and borders in themselves are nothing new. Yet they have received scarce attention within the burgeoning fields of childhood studies and border studies respectively, with limited consideration of how the two intersect, and of how, within the encounter, both are transformed. This volume enables the two fields of study to take a closer step to one another, enriching both in the process. It should be noted that, whilst thought-provoking reads, the ethnographic foundations for some articles within this volume appeared somewhat sparse. However, this in itself hardly renders the academic venture futile. The collection brings together accounts that serve as an important starting point, calling researchers within these respective fields to attention. From this standpoint, it is now necessary to delve deeper, investigating the dynamic and ongoing connections between these disciplines in such a way as to permanently transcend boundaries that might previously have limited both.

References

Anderson, B. (2006) Imagined Communities. London: Verso

Attard, S. (2013) Banishing the Abject: Constituting Oppositional Identities in a Maltese Harbour Town. [Unpublished PhD Thesis] Brunel University, London.

Halper, J. (2000) ‘The 94 Percent Solution: A Matrix of Control’, Middle East Report 216, 14-19.

*********

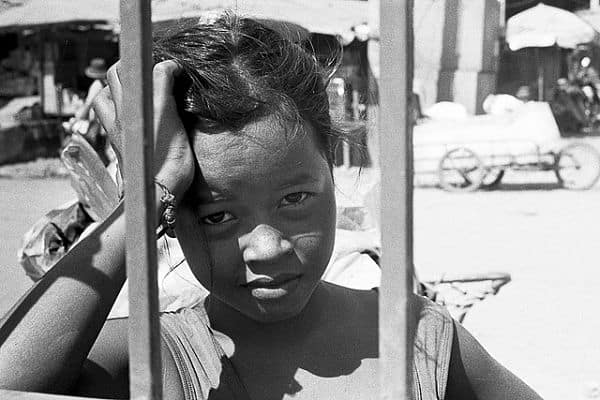

Featured image (cropped) by Quim Gil (flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Thank you for this review and your insightful reading of Children and Borders! Even though these issues have been a normalized aspect of everyday life in Cyprus and we have spent years studying them, we knew that there must have been many other situations around the world where borders impact young people’s everyday life and our call for chapters was really a first attempt to tap on this. Certainly the so called “migration crisis” has heightened the public’s awareness about the fact that children are literally caught on the border and this has helped to focus the discussion on how border policies and institutions impact the lives of those who are most vulnerable. From a disciplinary point of view, we hope that the conversation between Border studies and Childhood studies remains a productive debate that continues to confront the dilemma between seeing children as victims and children as agents of change. And we certainly believe that more ethnographic studies of these issues will highlight the nuances of this, albeit, false dilemma.