“Fate met Chance; I don’t know what she said to him but it was something about pictures and time” (Lorelei, 104).

It is nearly impossible, in writing this review, not to comment on the movie from which these photos derive; and which, in explicit and subdued ways, these photographs find a foil from which to play with, build on, and complement. The movie, which is set over a twelve-year period, provides and showcases the ways that we grow. Not just the son, but the mother, father, sister, parents, and friends. Linklater, the writer and director of the film, in his short essay in the book – entitled ‘Memories of the Present’ – tells us that the “conflation of film, time, and memory was the early protoplasm of the idea for the movie” (p.8). The book, much like the film, is the embodiment of the memory, time, and nostalgia that went into the entire process.

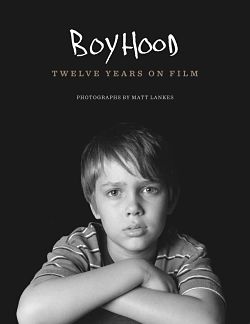

Filled with over two hundred images, Boyhood deftly gives us insights into not only the process and the characters, but the people who inhabit these roles and whose own lives are unfolding in front of the camera.

The book goes character by character, with each actor given a space to talk about the film, and a picture for every year of filming with a final picture that shows all of the images in chronological order. On each page opposite the photo are lines from the movie – some funny, some dark. Interspersed between the characters are a series of behind-the-scenes photos, with the book ending with portraits of the supporting cast and the crew.

The book goes character by character, with each actor given a space to talk about the film, and a picture for every year of filming with a final picture that shows all of the images in chronological order. On each page opposite the photo are lines from the movie – some funny, some dark. Interspersed between the characters are a series of behind-the-scenes photos, with the book ending with portraits of the supporting cast and the crew.

With this format, one begins to grasp the characters/actors in a different light. While the movie seamlessly flows forwards, the yearly portraits give concreteness to the passage of time. Ellar tells us, “I am growing up, the first time I watched the movie” (p.12), while Ethan Hawke says that “They [Linklater’s movies] are about us (human beings) and our relationship to the space and time that we inhabit” (p.88).

In many ways the book complicates the titular premise of the movie. Cathleen Sutherland, the producer, sums it up and says that “For me, Boyhood is a film about a single mom raising her kids and facing the inevitable abandonment by her college-bound child” (p.189). Patricia Arquette suggests that it is meant “to be a love letter to the middle class” (p.40) – a statement that does not do justice to the complicated portrayal of hard work, aspiration, and difficulty the Mom endures. The book is a way of complicating easy ideas of what the theme of the movie is and opens up new readings of each character, the relations between them, and the process of becoming itself.

The question one is left with – from the front cover of the young Son to the back cover of the Son at the end of the process – is, for me, about masculinity, childhood, and fatherhood. We are reminded of some of the Mom’s husbands/partners in the supporting cast photos; many of these men act as portrayals of the violent, oppressive, and dominating aspects of masculinity. We also see the way that fatherhood is a complicated role. Ethan explains that “Rick would tell me, ‘Dad is just taking up less space in his kid’s life.’ It stung like being a father does in real life” (p.88).

All this leads one to ask what might be the most important question of the book: has the Son become a ‘man’ rather than a ‘boy’?

If he has, when, why and how? Patricia tells us in the book that “He grew into a powerful and graceful man” and enjoyed seeing “the man he became in the boy he was” (p.40). On the other side, Ellar himself gives a less direct and dramatically different answer: “Almost all of my life I’ve been building this character [himself] to stand in place of my uncertainty but now I see that this character is just as fictional as Mason” (p.12). For an actor and character heavily influenced by photography, we see this wonderful image of the mask of masculinity – a by now common trope. Not only do we see the mask, but also that the reason and necessity of the mask is due to uncertainty; making clear that what lies beneath the mask is precarious and vulnerable, and that the mask itself is a powerfully complicated and heavily-produced piece of work.

Like the movie, one is able to read the book in any number of ways. One thing that is clear throughout is the tentativeness of time and relations, and yet the power of both of these forces. Not a photographer by training, it is hard for me to assess the photos simply on their own artistic merits, but it is easy to see the power and intensity that has gone into them and flows outwards from them. The book is a statement about the film, time, masculinity, and relationships, and is – for that – a wonderful celebration of all the difficulties and loves. If you enjoyed the movie, the book will serve as a reminder and a lens from which to re-watch the film.

**************

Featured photo by Wayne S. Grazio (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)