Introduction and Photographs by Judith Beyer, Book Review by Nina Johnen

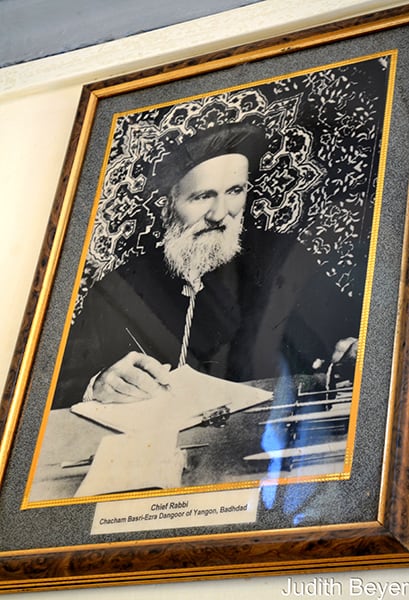

On an office desk in Yangon (Rangoon), the former capital of Myanmar (Burma): a bottle of wine – a present from Israel; few letters; a calendar with Jewish holidays; a stack of photographs from the recent Hanukah celebration. The tiny office is located in the only synagogue in Yangon, built from 1893-1896 on land given to the Jewish community that established itself in Yangon in the first half of the 19th century. While I am waiting for Sammy Samuel, the youngest community member, my eyes wander around the room until I notice the photograph on the wall: “Chief Rabbi Chacham Basri-Ezra Dangoor of Yangon, Baghdad.”

The Jewish community of Myanmar consists of only a few families, not more than twenty people altogether. They keep the building in shape and open its doors to anyone interested in the cultural heritage of the city. Several small shops are built inside the synagogue wall, facing the main street, and merchants pay the synagogue a small fee in order to be able to sell their products there. They also help to keep the place clean, as Moses Samuel, the host and manager of the synagogue, is getting old. His son Sammy, who resides in New York City most of the time, now takes care of administrative matters. He runs a tourism company bringing in Jewish tourists from the US who book “heritage tours” with him to Yangon to see the synagogue which houses a 120-year-old Sifel Torah from Baghdad. Outsiders thus regularly bolster the small community of “the last Jews of Myanmar”, celebrating holidays or Shabbat together, and enabling the reading of the Torah aloud, a ritual which requires that a quorum (minyan) of ten people be present.

The Jewish community of Myanmar consists of only a few families, not more than twenty people altogether. They keep the building in shape and open its doors to anyone interested in the cultural heritage of the city. Several small shops are built inside the synagogue wall, facing the main street, and merchants pay the synagogue a small fee in order to be able to sell their products there. They also help to keep the place clean, as Moses Samuel, the host and manager of the synagogue, is getting old. His son Sammy, who resides in New York City most of the time, now takes care of administrative matters. He runs a tourism company bringing in Jewish tourists from the US who book “heritage tours” with him to Yangon to see the synagogue which houses a 120-year-old Sifel Torah from Baghdad. Outsiders thus regularly bolster the small community of “the last Jews of Myanmar”, celebrating holidays or Shabbat together, and enabling the reading of the Torah aloud, a ritual which requires that a quorum (minyan) of ten people be present.

The history of the community is as interesting as its current initiatives and strategies to sustain itself. Because it is unique in Myanmar, there have been several stories published about the community over recent years, all similar since everyone primarily talks to Sammy; the articles have thereby become a historical record in themselves which trace the personal development of ‘the youngest Burmese Jew’ – from his studies in Israel and the United States; to his business endeavours, up to his marriage in February 2014, which was celebrated in the synagogue – the first Jewish wedding in Myanmar for twenty years.

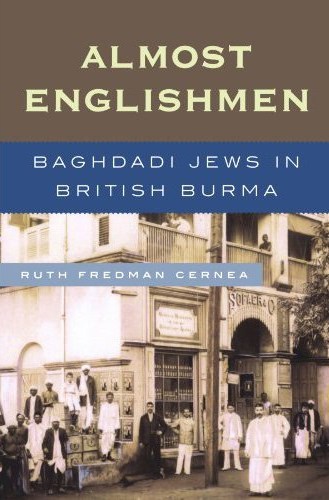

Anthropologist Ruth Fredman Cernea started her inquiry into Burmese Jewish life in 1987 as a tourist, but then spent almost two decades researching the history of the Baghdadi Jews in Burma and the family history of the Samuels in particular. In her book “Almost Englishmen” she weaves various strands of data together, including (auto-) biographies of various Jewish community members living in Yangon as well as abroad.

Book review by Nina Johnen

Almost Englishmen. Baghdadi Jews in British Burma. Ruth Fredman Cernea. 2006. Lanham: Lexington Books ISBN: 9780739116470, 202 pp.

Almost Englishmen. Baghdadi Jews in British Burma. Ruth Fredman Cernea. 2006. Lanham: Lexington Books ISBN: 9780739116470, 202 pp.

In her book Almost Englishmen. Baghdadi Jews in British Burma (2006) Ruth Fredman Cernea presents her research on the Jewish Diaspora of Baghdadi Jews in Burma (now officially called Myanmar) during the period of British colonialism from 1824 to 1948 with the aim of contributing “to the construction of this collective memory of Jewish life in Burma” (p. x). Cernea’s research is mostly based on memories and written accounts of members of the Burmese Jewish community or religious records of synagogues in Rangoon (nowadays called Yangon) in the south, and Mandalay in the heartland of Burma. In addition, she got in touch with the offspring of former family dynasties that today are spread all over the world from Australia to Germany.

The book gives a comprehensive overview of the development and establishment of the Baghdadi community in the social, political, economic and religious contexts of the time. The author’s main focus lies on the assimilation efforts of the Jewish community, the maintenance of their religious practices, their economic activities, and their social and political status with regards the English colonial power and other minorities and religious entities that co-existed in Burma over the centuries. “Almost Englishmen” manages to balance scientific research with an entertaining, reader-friendly style of writing, whereby the narrative style dominates the book. Many parts are direct quotes of written reports such as diaries, or are based on the narrations of eye witnesses and their offspring.

The book is of interest to academics as well as non-academics who are personally committed to the history of the Jewish diaspora in South(East)-Asia.

The introduction provides an overview of Baghdadi/Jewish Diaspora in South Asia around the 19th at a time when Calcutta was the site of its biggest community. Cernea traces the roots of Jewish diaspora movements back to the fall of the first temple in Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E, in the aftermath of which many found new homes in the Ottoman Empire and the Islamic world, especially around Baghdad in Iran. Due to these historic developments, the Baghdadis’ cultural heritage and teachings originated from Jewish religious authorities in Baghdad. This is in contrast to another group of Jews that also established themselves in South Asia, including Burma: the Bene Israel, whose religious traditions and beliefs originated from religious authorities in Jerusalem.

Cernea names different key economic, social and religious key factors whose symbiotic co-existence fostered the quick and sustainable establishment of Baghdadi Diaspora all over Asia. “Those patterns of communal responsibility, both to Jews and to the wider society in which they lived, were replicated in other locations where Baghdadis resided” (p. xxii). These factors include trading and family networks, language and social and economic independence, but also Judaism’s inherent concepts of social welfare, philanthropy, communal responsibility and the importance of Jewish educational institutions such as schools.

The first and second chapters give an overview of the British Empire’s economic interest in Burma, as well as the economic activities of the first Baghdadis in Mandalay and Rangoon. The first Jewish traders arrived and began to settle in 1840, building a synagogue in 1857. The author identifies these early traders as the founders of several Baghdadi family dynasties which successfully established themselves in colonialist society shortly after their arrival and which would dominate the future economic and social development of Jewish Diaspora across Burma until its collapse during the Second World War.

“The Saul family was intricately related by marriage to the Solomon and Sassoon families in Rangoon – and many of the other families in Burma – as sisters of one family married brothers of another and cousins married cousins throughout the generations” (p. 31). The social, economic and political activities of these family dynasties are the principal topic of the author’s discussion in her book.

Chapters Three and Four discuss integration processes and assimilation attempts by the Baghdadi upper class and give an overview of the co-existence of Jewish and British life and traditions in a country in which both cultures were foreign. In conclusion, the author suggests that Jewish assimilation was highly dependent on the political and social will of the British to accept them as part of their hierarchical society, though the orthodoxy of home, synagogue rituals and the establishment of institutions such as community centers, schools and the celebration of Jewish holidays also contributed to the preservation and strengthening of Jewish identity at the time.

Chapter Five discusses rising conflicts between the Bene Israel and the Baghdadi communities due to the different origin of their religious authorities. Exacerbated by the Baghdadi Community, these tensions eventually led to a court ruling in 1936 affirming the legal status of Bene Israel as Jews and their right to be part of synagogue communities.

Chapter Six and Seven describe the complete destruction of Burma by Japanese invasion and its impact on the Baghdadi community during and after the Second World War. In the course of growing anti-colonialist movements, Burmese resistance groups cooperated with Japan as they believed this would pave their way to national independence. Meanwhile, Baghdadi life in Burma was almost completely destroyed, as most community members fled to India. Cernea writes that attempts to revitalize the community by returnees after Burma’s independence in 1948 were impeded by the country’s new administration. In the course of a so-called “Burmanization” process, a variety of strict policies, impacting on the social and political rights of religious minorities, were implemented in such a way that by the 1960s most returnees had left Burma and migrated to Israel.

In Chapter Eight, the author investigates Burmese diplomatic relations with Israel. Due to the fact that Burma’s international political and economic role was, as a former British colony, isolated, strategic political and economic bonds between the two countries did not take off until the 1950s, providing a period of cooperation that only lasted until the beginning of the 1960s when the Burmese government declared a policy of strict self-reliance in all state affairs as the country became a socialist military dictatorship. The author closes with Chapter Nine, in which she gives a short overview of the traces left by the Baghdadi community in Burma, predominantly in Yangon.

Cernea reports that “Burma’s Jews are scattered around the world, primarily in London, Los Angeles, Sydney and Israel” and that actual Jewish community life is non-existent in today’s Myanmar. However, she also writes that “[w]hile many markers of Jewish life in Burma no longer exist, the coordinates of the community remain the same” (p. 130).

The Yangon Synagogue is in the care of Moses Samuels, a member of one of the biggest Baghdadi family dynasties, and there is hope that his son will take over the role of preserver of Baghdadi Jewish heritage in Burma, something which constitutes an important part of Burma’s diverse cultural roots.

Despite the narrow thematic focus on Jews in Burma, Cernea’s analysis provides material for comparative anthropological as well as sociological and political research which is concerned with the establishment of religious minorities abroad. It offers a contribution to the analysis of international migratory movements in terms of patterns of assimilation, and the socio-political role and rights of religious minorities within the contexts of statehood and citizenship before and after colonialism. In addition, the Baghdadis’ belief-based community bias can serve as another example of the positive impact of religion on the establishment of international trade networks in South and South-East Asia. In common with Islamic trade networks, these types of connections have helped diaspora communities gain social and economic recognition in foreign societies in both short and long-term time frames.

Unfortunately, the sources of Cernea’s research mostly attest to the lives of rich Jewish family dynasties that successfully managed to work their way into the country’s hierarchical colonial class system, thereby reaching a relatively high social and political standing and independence within Burmese society.

Information on the life of non-privileged or poor members of the Jewish community is limited, resulting in an imbalance of sources representing the perspectives of community members ranging from the high class elite down to simple vendors or traders.

This creates a gap in the attempt to portray Baghdadi diaspora life in all its facets, explained by the relative absence of historical records of “non-elite” Jews compared with those of family dynasties that had developed a tradition of documenting their families’ lives. As the latter were well educated and had a sense of the future cultural and religious benefit and significance of their written records, historical sources are dominated by their perspectives at the expense of other Jewish community members.

It is very interesting. My great greatfather was Yahudi who married my great great grandmother “Burmese” in Mandalay during King Mindon. He worked for Royal family and he spoke a few languages. After 1867, he and his wife left Mandalay. They came down to Monyo near Prome. He became a sort of merchant. He travelled to Mandalay and Monyo by boat. The last trip, he was killed and my grea greatgrandmother lost her husband and all money and whatever he belonged that trip. There was a lot of discrimination in those period. My grandmother had never said. All my neighbours were telling us, my grandmother and her family were not pure Burmese. Of course I knew that they were different. They were very fair skin and long noses and eyes. I finally asked my grandmother, she told me whatever she had heard from her grandmother. My grandmother and her sister lost their mother when they were young.

Two sisters were second generation, but Yahudi blood was still dominated. But their grandfather was very fair skin and their grandmother was dark skin. My grandmother had fair skin and she didn’t look like Burmese at all. But I forgot to ask my great great grandfather and I am not sure there was any relatives in Mandalay. My grand mother said he was a lone and he took his wife to Buddhist temples, but he was not Buddhist.

I am very interested if I could find any thing.

Kind regards

Peggy