Over the past few weeks my news and Twitter feeds have been overwhelmed with news, analysis and speculation about recent events in Crimea, Ukraine. The conflict in Crimea draws my attention for many reasons, but most of all because I spent 10 months on a Fulbright student grant studying Crimean Tatar language revitalization before entering graduate school. I never returned to this project after completing my MA, so I make no claim to expertise about the politics of what’s going on and the context of Eurasian security. Instead, I suggest two questions, and attempt to answer only one. First, what is at stake for Crimean Tatar communities given Russian military control over the region? I feel strongly that considering this question can provide much-needed texture to the up-to-the minute reports of political conflict and potential violence framed by ethnic difference in Crimea, where Crimean Tatar families have been threatened and property destroyed. The second question is relevant mostly for anthropologists, and will remain in the wings as I suggest insights from a project that I dug into and then set aside.

What does it mean for anthropologists to respond to the desire to provide relevant, up-to-date commentary on places and spaces we only visit occasionally, for particular reasons, and with allegiances to a discipline that values long-term engagement as a form of knowledge production? I’d like to use this as a space to open up a discussion about how to engage with past research, contained fieldwork experiences, and intellectual interests pursued and then abandoned.

Over the past week, reports of veiled threats and arson against Crimean Tatar neighborhoods and families have spurred much anxiety about the potential for ethnic violence in social media and news analysis. Crimean Tatar families have anxiously made contingency plans and defense groups; a photograph of a Crimean Tatar family leaving for Western Ukraine has been shared widely on Twitter. Journalists warn of the possibility of ethnic cleansing against the mostly Muslim Crimean Tatars as part of their call for the West to stand up to Putin. But as I refresh my feeds, grasp for understanding, and feel a pull to contribute to the conversation, I am not just thousands of miles and a few years away from my time in Crimea. I sense other kinds of distance: my out-of-practice Russian, lack of direct engagement in the region since I finished this first project, a shift in my research interests away from nationalism and ethnolinguistic recognition. But despite these distances, I’ve tried to offer something I’ve failed to find in the flurry of anxious reports of Crimean Tatar vulnerability in a Russian-occupied Crimea. Returning to this past project, I’ve sought to suggest what’s at stake for so many of the Crimean Tatars I met during my time in Ukraine, people for whom living in Crimea is a continual process of returning to homeland.

Returning and rebuilding across deportation

While it is true that many ethnic Russian inhabitants of Crimea align strongly with Moscow and support Russian control of the peninsula, many journalists and analysts covering events in Ukraine have rightly pointed out that a Russian majority in Crimea was first made possible because of a terrible tragedy: the 1944 deportation of individuals identified as Crimean Tatar. During and immediately following the deportation, by Crimean Tatar accounts, nearly half of the population died. Every family was touched by death. From that day, speaking of Crimea or Crimean Tatars became an inherently political act. Stories of Crimean Tatars as physically rooted in the Crimean homeland were told in exile as fundamental to individual, family and national histories as activists agitated for the right to return.

Beginning in the 1980s, and in greater numbers after the fall of the Soviet Union, Crimean Tatar activists orchestrated a mass return to Crimea; most of the tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars who were “returning” had been born in Central Asia and were travelling to the Crimean peninsula for the first time. For the sake of simplicity, I will often refer here to Crimean Tatar activists, but it is difficult to make a distinction between who is an activist and who is not when most Crimean Tatar adults living in the peninsula have moved thousands of miles to participate in a particular vision of homeland. Those who returned and began to chart new lives for themselves in Crimea encountered multiple, competing discourses about rapidly shifting conditions, including political and economic restructuring following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the establishment of an independent Ukraine. The label “Crimean Tatar” may obscure much ethnic, linguistic, religious, and political diversity among those claiming this identity, but the shared experience and memory of deportation and return provides a strong ground for those living in the peninsula to narrate personal and political history, even for those who are critical of political efforts to claim this story.

During my research in 2009 and 2010, I spent time with activists, educators and community leaders who sought to cultivate a political and cultural space for Crimean Tatars in contemporary Ukraine, especially as it relates to the Crimean Tatar language, now spoken mostly by the “oldest generation.” This time left me with a profound respect for these intense struggles, a respect I have yet to translate into lasting academic questions and answers. In my Master’s thesis, which became this project’s conclusion, I explored the complex discursive practices through which activists cultivate the place and time of “Crimea,” both before the deportation and during the always unfinished process of “return.” Sites of Crimean Tatar national education and language revitalization were important institutional nodes for this “return,” where pre-deportation and contemporary Crimea could melt together through dedication to the homeland and mother tongue within the space of the modern Ukrainian nation. As I re-read my past work to search for inspiration for this short essay, my interlocutors’ narratives of personal struggle and sacrifice take on new meaning in the context of a Russian-controlled Crimea. Even if Russian control of Crimea precipitates no violent acts against Crimean Tatar communities, the secession of Crimea from Ukraine would shake the foundations of these narratives and discursive realities.

Crimean Tatar identity in the frame of a multicultural Europe

My use of the tropes of return and rebuild are intentional here, as these are the frames through which activists lived and described their struggles. Although my research focused largely on language and education, I came to understand the efforts of educators and linguists to build and sustain Crimean Tatar national schools as part of a larger collaborative effort to access the Crimea of a pre-deportation past in and through participation in the Ukrainian project. This labor of return included seizing or otherwise obtaining unused land, building temporary and then permanent shelter by hand, and finding employment under extremely difficult economic conditions. Many consider this work still incomplete, constantly pointing to unfinished houses built on muddy fields and lamenting an inability to pay the way for family members in Central Asia who have yet to make the journey. The expansion of Crimean Tatar institutions such as newspapers and magazines, schools, theatre, political groups, craftwork and religious organizations is made a part of this ongoing process of return.

Those who participate in these institutions highlight continuity between pre-deportation and post-return Crimea by narrating their institutions or practices as reinstantiations of those destroyed by deportation and exile, rebuilt and developed through hard work and personal sacrifice.

Since 1991, activists have labored for this unfinished “return” within the administrative and discursive space of the Ukrainian nation. Activists and political leaders have often used their status as Ukrainian citizens to frame or even make possible their efforts to seek recognition and material support from Kyiv, Europe, and foreign institutions. I also found this discursive framing in nearly every interview with educators and linguists working on language revitalization. To give just one example, when I asked a school principal why parents might choose the Crimean Tatar national school over others, he did tell me that many considered it a duty to the nation and family to teach their children in a Crimean Tatar environment. But he also told me about the successes of his students in national Ukrainian dance competitions, and their ability to “speak beautiful Ukrainian.” Keep in mind that Crimea is a discursive space in which the Ukrainian language is often scoffed at and declared inferior to Russian. I met a Crimean Tatar scholar who had dedicated his life to preserving and promoting the Crimean Tatar language, and who had, among many other achievements, produced a tri-lingual Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar language dictionary. He offered me one and asked if I could bring it to a university in the United States, whichever university might find the greatest benefit from it. During our conversation, he would constantly use Ukrainian words as emblems of his allegiance to the much-contested project of Ukrainization in Crimea. I met family after family who had left a middle-class, urban life in Uzbekistan to make a life in Crimea; these families used the powerful metaphors of “rebuilding” and hard work as they declared the nation of Ukraine the space in which their children would continue this struggle.

So while the process of Ukrainization was contested in Crimea from the very moment of independence, the framing of Crimean Tatar ethnolinguistic autonomy and institutional progress has relied on a sort of sub-national deference to the Ukrainian nation. Until recently, Ukraine has been able to offer, or at least allow for the conditions of possibility for, resources, protection and recognition to Crimean Tatars as a religious and ethnic minority.This is precisely what many fear is lost in the Russian occupied of Crimea. “Who will protect us”, a Crimean Tatar man is quoted as saying in a recent blog post in the New Yorker[1], and media analysts are repeating the question with urgency. In Simferopol, the Crimean administrative capital where I did the majority of my research, many Crimean Tatars live in settlements at the outskirts of town due to the legacy of legal batters over land and housing rights. Having struggled to integrate into the infrastructures of the city over the past three decades, people are now living in fear that their isolated communities will be targeted. Painfully aware that there is no one to “protect” them, volunteers stand watch. What’s at stake in Crimea is therefore not just a shifting geopolitical context, but these very real material and discursive achievements upon which it was possible to “return” and “rebuild” Crimea. At present the discursive and political foundation of Ukrainian citizenship and participation in multi-cultural Europe are very weak ground upon which to rely.

The “here” of a Tatar Crimea

If I had to describe the power of these discourses of returning and rebuilding in just one vignette, as ethnographers are sometimes wont to do, I would return to an interview I did with Rustem[2], a teacher in a Crimean Tatar school in rural Crimea. On our first meeting, he described himself as a teacher and founding supporter of his school, explaining how every year he would work to convince parents to choose the “Tatar school” over the “Russian” ones. For him, the Crimean Tatar national school was a place to pass on language and traditions threatened by the deportation. He mourned the early loss of his parents, who had passed on traditions to his children, and he told me he was concerned about the future because he felt he would not be able to fill this role for his own grandchildren.

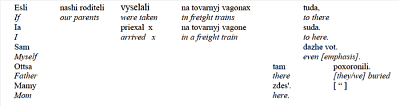

When I asked him why it was important to him to support Crimean Tatar projects like the school, he began to ramble, to trail off. Then he suddenly gathered his thoughts, speaking poetically in a few brief sentences that haunted my thoughts verbatim until I returned to the interview almost a year later. “If our parents were taken in freight trains there [to Central Asia], I arrived in in a freight train here [Crimea]. All by myself. We buried father there. Mother here.” Because I have been trained to appreciate the beauty of such poetics through linguistic analysis, I replicate my transcript here.

Although as a reader you may be unfamiliar with engaging in transcripts, I encourage you to follow me through this short analysis. I think that Rustem in these few words articulates a point much more subtly and poignantly that I could ever hope to. Invoking the image of “our parents” being transported to a Central Asian “there” (tuda) in multiple cars of a freight train, he is able to refer to not only his own parents who told this story, but also all Crimean Tatar generations who suffered on the fateful ride that left so many behind. He then compares this journey his own arrival “here,” in Crimea, all by himself (sam dazhe vot) linking the tragedy of deportation with his own continuous struggles. Contrasting places of exile and repatriation by mentioning where he buried his parents, he again shows his dedication to the “return” by dividing his family history across the gap of deportation and return. By referring to his parents’ burials – “there” and “here” – he also echoes his previous concern that his children can only benefit from his parents’ embodied knowledge of pre-deportation Crimea second hand. By laminating the deportation and return as complementary generational struggles through this parallel poetic structure, Rustem describes his struggles as the metaphorical extension of the struggle and pain of his parents. He immediately follows this by telling of his work in education as an extension of these struggles, including the opening of the very school we were sitting in, where “our children study.”

What strikes me most in hindsight about Rustem’s words is the precarity of “here” as a time and space that must be continually produced with intense effort in order to successfully achieve homeland.

I choose to foreground these isolated sentences because they illustrate how intensely activists’ relationships with the “here” of Crimea can be steeped in these histories, histories that we know as inextricable from the production of political and national projects: the USSR, various Soviet Republics, and contemporary Russia and Ukraine. The complex discursive emergence of a Crimean homeland for many of the activists I spoke with involved holding the past and present of “here” – that is, predeportation and contemporary Crimea – in tension across the often articulated history of deportation and return. Whatever is now happening in Ukraine, it is putting into question the very “here” that these narratives so self-consciously build upon.

Contested spaces and old field notes

One difficulty I have had in writing about Crimean Tatar language revitalization is to evoke the lived sense of urgency and passion while also writing within the anthropological tradition of studying nationalism and ethnolinguistic recognition. While anthropology is no longer interested in describing ethnic and linguistic histories as wholly “invented traditions,” there is still a tension in placing identities so important to individuals, families and ethnic groups within the complex, lurid history of nationalism. Writing about Crimean Tatars, this tension feels to me particular acute, as attempts to craft and manipulate Crimean Tatar ethnolinguistic identity for political projects reaches from Imperial Russian Administrators, to Muslim Jadidists, to Soviet policymakers, to contested spaces within contemporary Ukraine. Each of these regimes have sought to integrate Tatars into projects that have tied ethnolinguistic identity into higher orders of social belonging, have articulated constraints in which Tatars could develop themselves as a culturally distinct entity. But while Rustem’s words may emerge from these histories, they speak to a struggle that transcends them.

Some recent coverage of Crimea equates Stalin with Putin. It is certainly true that many seriously doubt Moscow’s ability or desire to provide adequate representation for or prevent physical and political violence against Crimean Tatars.

If blood here is shed, it will not be because of a Soviet-style deportation en masse, but emerge from clashes bearing no national insignia to which blame can be assigned. For many Crimean Tatars, whose ethnic identity and life histories are inextricable from the material and discursive rebuilding of a Crimean homeland in multiethnic Ukraine, Russian annexation of Crimea constitutes a threat to the very foundations of these lives and their lifelong efforts, at the same time that it removes the political and administrative ground for ethnolinguistic recognition and protection.

At this point, I return to my second question, which as been weighing on me as I write, even as it waits in the wings. I would wager I am far from the only one who has somewhat uneasily set aside research interests such as language revitalization and ethnolinguistic recognition in order to engage with other questions in anthropology. Yet when stories of political conflict rise to global attention, such as the recent unfolding of events in Ukraine, I know I’m not the only one who would like to encounter more of the subtlety and complexity that ethnography can offer. What does it mean to respond to fast-paced news cycles and developing “current events” when everything about ethnography is slow, often painfully so? And how can anthropologists provide much-needed texture to characterizations of the world through news when so much of our work is contained, deeply situated, and often partial or even abandoned? This essay is one attempt to engage with these questions. Although I sat down many times to write something that could sit side by side with journalistic analysis, the genre I found myself engaging in was not located in some abstract public sphere of news analysis but a discipline that still grapples with how to represent and understand ethnolinguistic difference in both the everyday and extraordinary moments of human life.

Perhaps there are others sitting uncomfortably with their Twitter feeds and keyboards, those with projects that are in progress, finished, or left to the side. I would hope that there are.

[1] http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2014/03/who-will-protect-the-crimean-tatars.html

[2] This name has been changed