This week Allegra focuses on an exciting new feature incorporated into our beloved website a while back: namely Projects! What this feature entails are collaborations – events, even research ventures – in which our website is centrally involved in. We are very pleased to introduce the second such project, namely the workshop entitled Rethinking political agency in the Middle East: Engaging political anthropology which will take place in Fiesole at the European University Institute this week, on 19-20 May 2016.

This workshop will be realised with the conference grant that two of our Allies – Luigi Achilli and Antonio De Lauri – were recently awarded by the Wenner Gren Foundation. Below is a closer description of the event, with ample coverage to come.

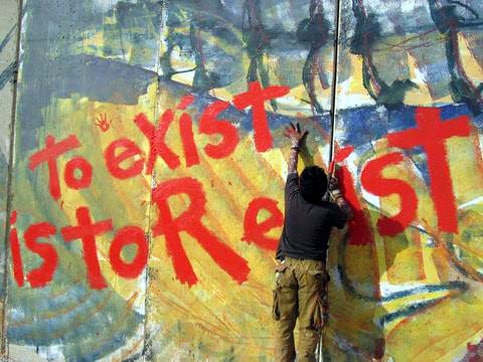

The workshop intends to bring ethnographic research in the Middle East into conversation with anthropological debate on political agency. The last decade has witnessed renewed concern with “agency” in anthropological debates and publications. This reflects a critical engagement with a Foucauldian work on “subjectification”, which has sought to problematize the idea of agency as the capacity of a free agent to translate his/her values into actions (Candea 2011; Keane 2003; Laidlaw 2001, 2002; Mahmood 2001, 2005; Verkaaik 2010; Yurchak 2006, 2008). These authors warn against romanticising resistance by misattributing it to forms of agency that cannot be reduced only to conscious or unconscious moments of opposition to domination. We understand political agency as not simply the capacity to act politically against overarching forces and practices of domination, but rather as to the ability to effect change (Mahmood 2005). We believe that such an approach can offer new insights into the nature and experience of the political in a region where the complexities of political change often left authors recognizing as effective only those actions that are conducive toward freedom and liberation from subjugating forces (Wedeen 1999).

Political agency represents a crucial analytical frame both to observe contemporary social and political transformations as well as to define the role of anthropology in the interpretation of our age.

Over the past decade, a conspicuous body of ethnographic research in the Middle East has produced highly sophisticated and nuanced analyses of the role played by urban masses either as participatory agents in the political reforms and revolutions or as mediating forces against such actions (most notably Allal 2012; Beinin et Vairel 2011; Bouziane, Harders et Hoffmann 2013; Brahimi 2011; Catusse et Vairel 2010; Dorai et Puig 2012; Harb el Kak 1998; Ismail 2006, 2013; Wedeen 1999, 2008). However, as Altorki argues, “theories of contentious collective action and revolution are available, but anthropologists have not, in the main, worked in these areas” (2015). In addition, lured by the spectacular clarity of political demonstrations and acts of violence that have dramatically upset Tunisia, Egypt and Syria, many Middle East scholars and political analysts have, with few exemptions, missed the complexity of political change in the region. As several scholars have argued, much of this literature continues to share a narrow understanding of political agency (Bayat 2013).

This conception produces a set of interrelated problems. First, although “resistance” – as an ideal form of action – is surely an important facet of political agency, its centrality may lead to overemphasise the significance of this dimension in political change. A further interrelated problem with this notion of agency is entailed in the unspoken presumption of what a person’s actual or ultimate goal is. By taking for granted the universality of a desire to act and assuming that this may be inspired only by a genuine yearning for freedom and equality, this approach recognises as effective only those actions that are conducive toward this end. In making this assumption, however, such an approach denies “dimensions of human action whose ethical and political status does not map onto the logic of repression and resistance” (Mahmood 2005, p. 14).

With this workshop, our first aim is to bring together a group of junior and more established scholars who have been seeking, in diverse ethnographic sites and in hitherto isolated fashion, to bring the theoretical insights of recent anthropological work on political agency to bear on the study of political change in contemporary Middle East.

There is a number of reasons to combine these two bodies of literatures. The recent political turmoil in the region provides a wealth of material for contemporary debate and fine-grained ethnographic comparison: about the nature of political change; about the comparability of post-colonialisms; about the performativity of power and the exercise of sovereignty; or the new kinds of structural dependence that emerge when nominal “independence” coincides with the orthodoxy of neoliberal economics.

Our second aim in holding this workshop is to bring together scholars whose research on political agency and change in the Middle East has sought to develop alternative ways to thinking about political action and political subjectivity, and whose work has thereby come to envisage forms of agency that cannot be fully explained by universal approaches of force/power relations such as “pouvoir-savoir” and sovereignty. We feel the urgency to set up an organic and ground based political anthropology of the Middle East so as to test and expand existing accounts of political agency that have sought to go beyond the limitations of the Foucault-Agamben canon (Yurchak 2008, and comments by D. Boyer).

The main goal of the workshop is to investigate alternative ways of approaching political change (and stasis) by looking at forms of agency ignored by much of the literature in the region. Yet, through the workshop, we “un-bound” the very idea of “Middle East” by exploring connections and investigating phenomena that transcend geographical boundaries.

Workshop participants

Antonio De Lauri (University of Milan-Bicocca)

Luigi Achilli (EUI)

Deniz Gokalp (American University in Dubai)

Latif Tas (SOAS, London)

Alessandro Monsutti (Graduate Institute, Geneva)

Mjriam Abu Samra (University of Oxford)

Paul Anderson (University of Cambridge)

Martyn Egan (EUI)

Julie Billaud (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology)

Follow the development of the debate on Allegra.

Selected bibliography

Abowd, T., 2007, “National boundaries, colonized spaces: the gendered politics of residential life in contemporary Jerusalem”, Anthropology Quarterly, 80(4): 997-1034.

Abu-Lughod, L., 1989, “Zones of Theory in the Anthropology of the Arab World”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 18: 267–306.

Abu-Lughod, L., 2013, Do Muslim Women Need Saving?. Harvard University Press.

Achilli, L. 2014, “Disengagement from politics”, Critique of Anthropology, 34(2): 234-257.

Achilli, L., 2015, “Becoming a Man in al-Wihdat: Masculine Performances in a Palestinian Refugee Camp in Jordan”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 47(2): 263-280.

Adely, FJ., 2012, “‘God Made Beautiful Things’”: Proper Faith and Religious Authority in a Jordanian High School”, American Ethnologist, 39(2):297–312.

Ahmed, L., 1992, Women and Gender in Islam. Yale University Press.

Allal, A., 2012, “Trajectoires ‘révolutionnaires’ en Tunisie : Processus de radicalisations politiques 2007-2011”, Revue française de science politique, 62: 821-841.

Allen, L., 2009, “Martyr Bodies in the Media: Human Rights, Aesthetics, and the Politics of Immediation in the Palestinian Intifada”, American Ethnologist, 36(1):161–80.

Allen, L., 2013, The Rise and Fall of Human Rights. Cynicism and Politics in Occupied Palestine. Stanford University Press.

Al-Mohammad, H., 2010, “Towards an ethics of being-with: intertwinements of life in post-invasion Basra”, Ethnos, 75(4): 425-26.

Altorki, S., 2015, A Companion to the Anthropology of the Middle East. Wiley-Blackwell.

Anderson, P., 2013, “The Politics of Scorn in Syria and the Agency of Narrated Involvement”, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 19(3): 463-481.

Antoun, R., 2000. “Civil society, tribal process, and change in Jordan: an anthropological view”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 32(4): 441-63.

Asad, T., 1986, The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam. Georgetown University.

Asad, T., 2003, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford University Press.

Asad, T., 2007, On Suicide Bombing. Columbia University Press.

Bayat, A., 2013, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East. Stanford University Press.

Beinin, J., Vairel, F., 2011, eds., Social Movements, Mobilization, and Contestation in the Middle East and North Africa. Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P., 1979, Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bouziane, M., Harders, C., Hoffmann, A., 2013, Local Politics and Contemporary Transformations in the Arab World: Governance Beyond the Center. Palgrave Macmillan.

Brahimi, A., 2011, “Libya’s Revolution”, The Journal of North African Studies, 16(4): 605-624.

Candea, M., 2011, “‘Our Division of the Universe’: Making a Space for the Non-political in the Anthropology of Politics”, Current Anthropology, 52: 309–334.

Catusse, M., Vairel, F., 2010, “Question sociale et développement”, Politique africaine, 120: 5-23.

Chatty, D., 2010, Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press.

Dahlgren, S., 2010, Contesting Realities: The Public Sphere and Morality in Southern Yemen. Syracuse University Press.

De Lauri, A., 2014, Law as an Anti-Value: Justice, Violence and Suffering in the Logic of Becoming, Anthropology Today, 30(3): 22-25.

De Lauri, A., 2016, ed., The Politics of Humanitarianism. Power, Ideology and Aid. I.B. Tauris.

Deeb, L., 2006, An Enchanted Modern: Gender and Public Piety in Shi’i Lebanon. Princeton University Press.

Deeb, L., Harb, M., 2013, “Choosing Both Faith and Fun: Youth Negotiations of Moral Norms in South Beirut”, Ethnos, 78(1): 1-22.

Deeb, L., Winegar, J., 2013, “The Politics of Middle East Anthropology from the End of the Cold War through the War on Terror: Insights from a Transitional Generation.” In Anthropology of the Middle East and North Africa, eds., Sherine Hafez and Susan Slyomovics. Indiana University Press.

Dorai, K., Puig, N., 2012, L’urbanité des marges: Migrants et réfugiés dans les villes du Proche-Orient. Téraèdre.

Fassin, D., 2008, “The Humanitarian Politics of Testimony: Subjectification Through Trauma in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict”, Cultural Anthropology, 23(3):531–58.

Feldman, I., 2008, Governing Gaza: Bureaucracy, Authority, and the Work of Rule, 1917–1967. Duke University Press.

Foucault, M., 1980, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972/1977, Harvester Press.

Furani, K., Rabinowitz, D., 2011, “The Ethnographic Arriving of Palestine”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 40: 475–91.

Gabiam, N., 2012, “When ‘Humanitarianism’ Becomes ‘Development’: The Politics of International Aid in Syria’s Palestinian Refugee Camps”, American Anthropologist, 114(1): 95–107.

Ghannam, F., 2011, “Mobility, Liminality, and Embodiment in Cairo, Egypt”, American Ethnologist, 38(4): 790–800.

Gilsenan, M., 1996, Lords of the Lebanese Marches: Violence and Narrative in an Arab Society. I.B. Tauris.