The Darjeeling Distinction, as Daniel Münster notes in his thoughtful review on Allegra Lab, is about both a place and a product. Darjeeling is nestled in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal. It shares borders with Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh, as well as the former kingdom (and now Indian state) of Sikkim. Darjeeling was founded by the British in the 1830s as a “hill station.” Since the surrounding region was sparsely populated, the British recruited thousands of laborers from Nepal to clear-cut forests and construct roads and buildings. Boarding schools and sporting clubs sprang up alongside bureaucratic offices, while imported conifers and garden plants brought the landscape in line with British ideals of a restorative “nature.” Thanks to the influx of Nepali labor, Darjeeling quickly became a site of social reproduction, but through the development of the hill station, agricultural production steadily intensified. The historical origins of Darjeeling (the place) as a hill station and mountain refuge are inseparable from the contemporary status of Darjeeling (the product) as a globally circulating luxury beverage.

While luxury is certainly important to Darjeeling’s identity as a product and as a place, I first went to the region to study its most recent incarnation, as a site and emblem of ethical trade. On grocery store shelves in the US, I saw Darjeeling tea adorned with many labels—such as organic, fair trade, Rainforest Alliance, and Demeter. One of these labels stood out to me in my early research.

I began to see a remarkable disconnect between the aims, ideals, and marketing messages embedded in fair trade labels and the reality I saw on the ground on Darjeeling plantations.

Despite this disconnect, tea plantations—grounded in histories of colonial control, land exploitation, and landscape transformation—are being enveloped into a global market for fair trade certified products with increasing frequency. Darjeeling, as I learned during my research, has served as a kind of testing ground for fair trade certification on plantations. I began my research by asking the question: how can a plantation ever be fair?

In order to understand how a plantation could be fair, I had to ask first what a plantation was, as a social, environmental, and economic form. This question emerged from my reading at the time of interdisciplinary discussions of agriculture in geography and food studies. Among other things, these studies tracked the resurgence of small scale, “local” food in response to the industrialization of agriculture around the world. This literature critiqued the capacity of fair trade certification to bring post-colonial small farmers into the market for socially responsible food. Despite all the talk about small farmers, the fair trade-certified tea you buy today at your local store still comes largely from plantations, especially if you are buying black tea (the green tea produced in East Asia is a product of different historical and ecological circumstances and is a very different product). The plantation seems to stand in opposition to our commonly held ideas of what fair trade should be, even in its ideal form.

In order to understand how a plantation could be fair, I had to ask first what a plantation was, as a social, environmental, and economic form. This question emerged from my reading at the time of interdisciplinary discussions of agriculture in geography and food studies. Among other things, these studies tracked the resurgence of small scale, “local” food in response to the industrialization of agriculture around the world. This literature critiqued the capacity of fair trade certification to bring post-colonial small farmers into the market for socially responsible food. Despite all the talk about small farmers, the fair trade-certified tea you buy today at your local store still comes largely from plantations, especially if you are buying black tea (the green tea produced in East Asia is a product of different historical and ecological circumstances and is a very different product). The plantation seems to stand in opposition to our commonly held ideas of what fair trade should be, even in its ideal form.

On my grocery store shelves, tea produced on plantations in India (as well as Sri Lanka and East Africa) still seems to sit a bit too comfortably alongside locally grown organic kale and artisan pork, as well as ethically sourced coffee from Central America.

I see fair trade as a kind of a conceptual and institutional vehicle for this collapse of geographies, land tenure systems, and political economies of production and circulation.

This collapse, along with conversations that I had with colleagues and fellow students in the Geography and Rural Sociology departments at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, inspired me to cross-pollinate perspectives on food and agriculture in the Americas with concerns in South Asian studies about legacies of colonialism and postcolonial questions of rights.

In his review, Münster asks why I do not engage more with the question of organic certification. This is a fair point, considering that the fair-trade certified tea plantations on which I worked, arguably, have much more in common with the industrial organic production systems Julie Guthman has described in California than the fair-trade Nicaraguan coffee cooperatives that Bradley Wilson—another geographer—has studied in rich detail.

In answer to Münster, I would say, first, that although the plantations on which I worked were nearly all certified organic, organic certification and production methods had little meaning to the workers that I spoke with. On some Darjeeling plantations, managers lauded organics, while on others, workers told me that pesticide and fertilizer spraying continued. (Indeed, Darjeeling teas found to contain pesticide residues are often sent back to their producers from places like Germany, rejected by buyers dedicated to organic standards.) Sometimes, I was shown bug-ridden compost bins by management during plantation tours. Despite numerous inquiries, I could never quite figure out when and how this compost was used, or—more anthropologically important—what it meant to tea plantation workers when it was used.

Readers of Allegra Lab may already be aware that different national organic certification programs have different definitions of “organic” and different legal frameworks for enforcing those definitions. As anthropologists of law and regulation, we need to better understand the overlaps and divergences among these. As a globally circulating product that traverses several different national organic rubrics, Darjeeling tea might make a good case study.

But organics are just one part of an even larger story. For example, I have collected a good deal of ethnographic material on biodynamic (or Demeter-certified) tea production. On biodynamic plantations, workers must regularly collect and transport cow dung to make biodynamic “preparations,” most notably fertilizer, in addition to plucking and pruning tea bushes. Münster’s question about organic certification has prompted me to think through this material, and I hope to write more about it. My interest is as much in the environmental impacts of biodynamic certification as in intersections between ethical trade and new-age philosophy. Biodynamic farming practices are undergirded by the anthroposophical teachings of Rudolf Steiner (of Waldorf school fame). The cow is the central animal in biodynamic practice. There are unexplored connections here between Hindu perspectives on the “sacred cow” and consumerist New Age ones. In biodynamics, we see environmental, social, religious ethics overlapping across time and space.

Still, what troubles me is that organic and biodynamic certifications, despite their restrictions on inputs to soil, have little to say about land tenure. Herein lies a moral quandary for these movements. Both big and small producers can be organic, for example, but are these land tenure systems really commensurable? In my case, fair trade allowed me to think critically about how land tenure matters to ethical trade.

Münster also rightly points out that the book selectively employs a multispecies perspective. I drew on a multispecies framework to describe how women workers understand the plantation. When I was writing the book, I was invigorated by a wave of exciting conversations around more-than human-landscapes, and I found that a multispecies perspective opened up my own material.

It remains important to me that we understand the plantation as a more-than-human form, and that the specifics of environmental conditions continue to be part of plantation studies. Understanding the relationships (positive, negative, and otherwise) between plantation women and tea bushes provides a check against a temptation to see plantation labor as only an alienating experience.

A multispecies perspective, in my opinion, lets industrial agricultural laborers voice their own understandings of their lives and work without having those understandings written off as “false consciousness.” Anna Tsing (2012) has argued that plantations “remove the love” between people and plants. I agree with Tsing that plantations depend upon coercion and exploitation, but her question provoked me. What is love? What is the place of love in labor studies?

I suppose I am concerned less with love than with more thorny affective states. Love is definitely not the way to describe plantation workers’ relationships to plants, but the tea we know today is inseparable from the plantation form. Has a tea bush in India ever been loved? Love was not there in the first place to be removed. So what is there? What kinds of relationships, what forms of human-human and human-nonhuman sociality are produced on plantations? This last question was what concerned me and compelled me to adopt a multispecies perspective, though I did only develop that perspective in one chapter.

I appreciate that Münster sees this and other “loose ends” “as a promise of more to come.” In two ongoing projects, I am thinking in a multispecies framework to explore other aspects of industrialized agriculture and urban space in Darjeeling and Northeast India more generally.

The first is a long-term project about the afterlives of the hill station. I am exploring the environmental dimensions of the Gorkhaland agitation, the longstanding movement for Gorkha subnational autonomy I describe in Chapter 5 of the book. Even today, over six decades after the end of British rule, tea plantations, tended by the descendants of Nepali labor recruits but owned by British and later Indian companies, remain pillars of the region’s economy. Despite living in the region since the mid-1800s, these Indian Nepali workers, or Gorkhas, continue to claim that they are not acknowledged as full Indian citizens. For decades, Gorkhas have struggled to break Darjeeling off of the state of West Bengal and to create a separate state of Gorkhaland within the Indian federation. But what is being separated is a much a question of whom. While many analyses of subnational movements in India characterize them as struggles for land, struggles with land are equally important to Gorkha senses of belonging. In my new project, I ask how contemporary Gorkha encounters with environmental problems, including landslides, a crumbling colonial infrastructure, and pest animals, provide insights into the relationship of land to identity in Indian subnationalism, as well as in political and environmental anthropology. Gorkha land and Gorkha identity can both be seen as “edge effects:” the material and ideological results of encounters between ecosystems, species, and ways of occupying space.

I ask how the Nepalis who remained in Darjeeling after independence have worked to assert belonging there. Hill stations are examples of what environmental philosopher Val Plumwood (2008) calls “shadow places:” places materially and imaginatively oriented to the sustenance and the enjoyment of others. Making claims to belonging in shadow places is difficult. In shadow places, as Plumwood (2008, 139) writes, “[t]he very concept of a singular homeplace or ‘our place’ is problematised by the dissociation and dematerialisation that permeate the global economy and culture.”

Though British capital has long dried up, Gorkhas today still find themselves working to maintain Darjeeling’s colonial infrastructure and to keep its tea and timber plantations viable. Indeed, their claims to political control over Darjeeling paradoxically depend upon such maintenance work.

Questions about the rights of Gorkhas to place are bound up with questions about the ecological effects of tea plantation monoculture, the sustainability of forests, and the appropriateness of a sprawling city in the steep Himalayan foothills.

Gorkhas recognize themselves as the collective inheritors of a colonial infrastructure: one that is visibly decaying as capital recedes, while rainfall, population growth, and other kinds of wear continue to take their toll.

The second project is on reform in the Indian tea industry. As I discuss in The Darjeeling Distinction, Darjeeling has a special caché on the tea market. Many other tea-growing regions in India, however, are not so endowed. Such regions, most notably the Dooars, adjacent to Darjeeling, produce undifferentiated (and un-certified) black tea for both foreign and domestic markets. In the Dooars, many plantation owners, faced by a flooded market and decreasing yields, are closing their plantations. Plantation closure allows owners to keep their leases on land but excuses them from the obligation to provide workers with basic food rations, housing, and other facilities. Plantation closure is having deadly consequences. Indeed, some workers in the Dooars are reportedly starving to death. The monocultured landscape has turned from a source of work and minimal social support into a killing field. I will be thinking through these ideas in a School for Advanced Research (SAR) seminar on “How Nature Works” in September 2016, which I am co-convening with Alex Blanchette (Tufts University) and Naisargi Dave (University of Toronto). The goal of the seminar is to cross-pollinate posthumanism with labor studies.

Over the last few years, I have been excited to see more scholars coming together around the problem of the global plantation. Daniel Münster’s careful review of The Darjeeling Distinction has raised important additional questions not only about alternative ways of producing agricultural commodities, but also about alternative ways of seeing and theorizing these commodities.

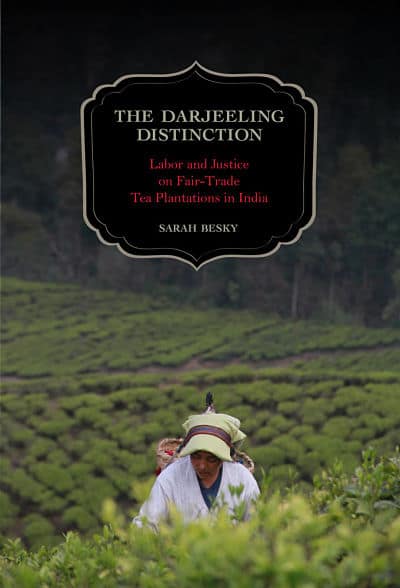

Featured image by shankar s. (flickr, CC BY 2.0)