On Saturday 28 November Alun Withey and I hosted Framing the Face: New Perspectives of the History of Facial Hair, a one day conference funded by the University of Hertfordshire and the University of Exeter. Alun has just begun a three year Wellcome Trust funded project on facial hair and I have been working on a history of men’s sexual health in the seventeenth century that has (surprisingly) led to lots of facial hair related material. We thus wanted to bring together scholars working across temporal and geographic boundaries to see what conversations would emerge.

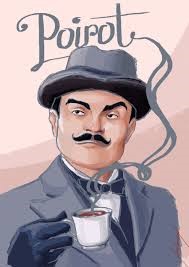

The day started with a fantastic interdisciplinary panel exploring the role of moustaches on canvas, stage, and screen. Art historian Victoria Alonso Cabezas examined the representation of young male painters in nineteenth-century Spanish art. We saw that several paintings included shadows of potential facial hair indicating the artist’s entrance in adult manhood. Victoria also showed how some Spanish artists introduced facial hair into their self-representations following involvement in the military or more usually following marriage. Het Philips then considered the role of moustaches as a marker of ‘creepy’ objectionable masculinity in television and film. Moustachioed characters in Trainspotting and Orange is the New Black, for example, display excessively violent, and often sexually violent, forms of masculinity that Het suggested masks the moral failing of more ‘normal’ male characters. The enjoyment of these masculinities in popular culture is, she argues, rather disconcerting. But having this immediately visually obvious character creates a trope to be subverted, where ‘normal’ men are revealed to be even more morally dubious than the moustache wearing villains. The panel was completed by makeup artist Helen Casey who explored three case studies where moustaches have been central to the creation of a male character: Charlie Chaplin’s tramp clown, Groucho Marx’s stage persona and David Suchet’s Hercule Poirot. Chaplin made a conscious choice to reject the traditional painted on stubble of tramp clowns played into his desire to have everything about the persona be a contradiction –the tramp clown who is actually a gentleman down on his luck. Poirot’s moustache, meanwhile, portrays everything about the character in one clear visual signifier; he is a man that is precise, clean, fussy and isolated.

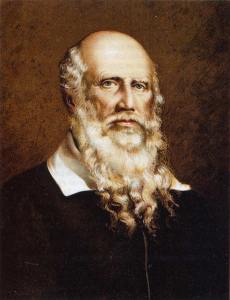

The speakers in the second panel looked at facial hair more broadly and crossed gender lines. Emily Cock questioned the ways in which early modern literature utilised the beard as a key characteristic of a bawd. These one-time prostitutes turned madams were inversions of all that was sexually attractive. They were not though described as having full beards but were endowed with prickly hairs upon their chins. This facial hair excluded them from the realms of the feminine but did not bestow masculinity. Ellie Rycroft also took us into the world of early modern England examining the lifecycle of boy players and the roles they played on the stage. Beards, as she pointed out, did not suddenly appear but grew over time. Young male actors slipped through social categories and may have had to employ false beards to play adult men. However, as Rycroft noted, in the seventeenth century concern about false beards perhaps meant companies of players moved towards using actors with their real facial hair at its different stages of development. While young and beardless these boys played roles like the page, a bawdy role, which unnerved society by connecting youth to criminality. The growth of facial hair moved youths into the role of gallant or soldier. The extravagance and impermanence of Gallants, who shaved their beards, represented a real threat to society, whilst soldiers, whose martial masculinity was repeatedly asserted through excessive beard growth, suggested the wildness and disorder of unbridled masculine activity. The final paper in the paper was delivered by Hanna Weibye who described the complex representational qualities of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn’s beard. The nineteenth-century creator of a gymnastic movement in Germany, she argued, perhaps used his beard to signify his sense of difference to the ruling class of German bourgeoisie. While they were clean shaven or wore neat short beards, Jahn’s rather long beard associated him with artisans and a nostalgic Germanic past. His beard was a memorial to his patriotic youth movement that the government refused to support. It was sign of his constancy, loyalty to the state and the fact that he was alienated from his own time.

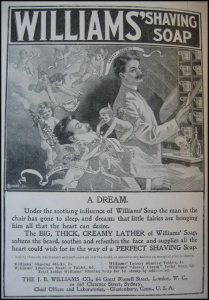

From the representational qualities of beards the conference moved on to think about choice and consumerism. John Gagné revealed the intriguing example of Italian beards around 1500. After charting the rise and fall of facial hair in the Roman epochs, he explored the beard wearing of Francesco Gonzaga, who was unusual amongst European princes for wearing a beard. This coincided with Gonzaga’s fight against the French, and under French rule Milanese men were ordered to shave off their beards within three days. Their choice was thus nominally removed from them by a French government who feared that beards were connected to wickedness and sin and that false beards allowed for the disguise of men who had committed crime. Enforced shaving was an indignity to the Milanese who sought diplomatic redress and wore their beards as a sign of mourning for their city, and their defiance of their French overlords. Moving into the nineteenth-century Justin Bengry delved into the world of shaving adverts and showed how shaving companies sought to instill anxieties about disease and the vulnerability of the masculine body into their potential customers. Concerns that could of course be eased and abated by the use of the ‘right’ shaving products. Adverts both showed the man at home as model of domestic patriarchal bliss, and showed men in the rugged outdoors, escaping the confines of domesticity. Bengry argued that adverts invoked domestic, imperial, modern and traditional tropes to tie their products to extant and new identities. They created tensions in masculinity – showing men that it was fragile, defensive and at risk – in order to encourage men’s consumer choices. Christopher Oldston-Moore concluded the speakers’ sessions by taking a longue durée approach to understanding choices and trends in facial hair fashion. He suggested that there have been four relatively brief periods of ‘bearded’ history in a western tradition dominated by clean shaven faces. These beard wearing eras were provoked, he argued, by shifts in the foundation of masculine authority towards the ‘naturalness’ of the male body.

The day concluded with a plenary paper by Margaret Pelling that took us on a tour through early modern portraiture and the self-presentation of hair and facial hair. Pelling pointed out that the body and clothing have tended to be considered by historians separately from hair and facial hair. Heads, she noted, have received a lot of scholarly attention because they force themselves on our notice. Yet sexuality and sex, which have often been considered, might not be the best ways to think about the history of the beard: Shylock’s beard, for example, was central to his identity but this was not simply about his masculinity. Hair after all was visible and alterable and could be shaped to show ritual, religious and social status. Beards and hair were not covered by sumptuary laws that, although not rigidly enforced, suggested that appropriate ways to manifest these outward signs of status through clothing. This is intriguing given that the head and hands were the most exposed and vulnerable parts of the body. Facial hair could be used as a screen to hide the face, but is easily distorted by emotive movements meaning that in many contexts it exaggerates rather than hides the face and emotions. Another way to read the wearing of facial hair in this era, Pelling offered, is to think about the static nature of the court which might have given rise to boredom and the growing of facial hair to provide a diversion. Alternatively, older men in particular were prone to wear facial hair, which might have acted as a compensation for male pattern baldness. Pelling’s paper summarized a key theme of the day which is that there are many ways to think about and understand beards and facial hair in the past. And importantly points out that there is much ground still to be covered.

This post was originally published here.

(Featured image: Wellcome Images – CC BY 4.0)