José Esteban Muñoz (born 1967) died in New York City in December 2013 at the age of 46. His untimely loss is another great blow not only for queer theory and critical theory, but also for the fields of performance studies and cultural studies.

Muñoz was a Cuban American academic, a professor and former Chair of, the Department of Performance Studies at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. He was born in Havana, Cuba in 1967, and shortly thereafter relocated with his parents to the Cuban exile enclave of Hialeah, Florida. He received his undergraduate education at Sarah Lawrence College and his doctorate from the Graduate Program in Literature at Duke University, where he studied under the tutelage of queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. Sedgwick died also prematurely of breast cancer in 2009, another recurring source of mourning for queer theorists due the role that her critical writings had in shaping the field of queer studies.

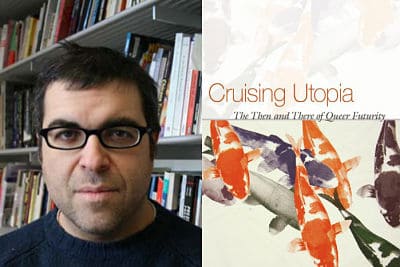

Muñoz’s first book Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (1999) examines queer and racial minority issues from a performance studies perspective. But it was his second book, Cruising Utopia: the Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press 2009) that has had a major impact for queer studies.

In Cruising Utopia, Muñoz argues powerfully against the romance of singularity and negativity of the so called antisocial turn in queer theory. Instead of the opting for the death drive and giving up any faith in queer reform, as Lee Edelman suggested in his 2004 book No Future, Muñoz promotes an idea he calls ”hope’s methodology”. As we are not yet queer we should reject the here and now and insist on the potentiality or concrete possibility of another world, Muñoz claimed in Cruising Utopia: ”Queerness is that thing that lets us feel that this world is not enough – the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility of another world.”

The definition of sex as anti-communitarian, self-shattering and anti-identitarian has produced a counter-intuitive but crucial shift in thinking away from projects of redemption, reconstruction, restoration and reclamation and towards what can only be called an anti-social, negative and anti-relational theory of sexuality in queer theory – but the under-privileged category actually sustains purposive and intricate modes of oppositional knowledge, many of which can be associated with and linked to forms of activity that we have come to call “queer”, wrote a good friend and collaborator of Munoz, Judith Halberstam in 2005. The notion of ‘hope’ in Munoz’s work comes exactly from this anti-highbrow theoretical place; from the racialized under-privileged position, where future never totally manifested itself and hope never stayed long enough to be given away.

Of course, I do not intend to put Edelman and Munoz to entirely oppositional positions regarding the question of race as it would be a wrongdoing to both of them. Edelman’s contribution to anti-social queer theory is thoroughly controversial in itself and can be read as not only as an intellectual, fierce and definitely polemic but partly also even a romantic political manifesto on its own right: the queer subject stands between heterosexual optimism and its realization, it says no to the nostalgic and paralytizing yearning for the lost past and the redemptive future which is promised in the always-already impossible recognization – For Edelman, the promise of “rights” promises nothing but new limits and exclusions as queer is by definition about excess, negativity, nonsense, anti-productivity and unintelligibility. For Munoz, however, the world is still in need of some reinvention.

Sadly, the death of José Esteban Muñoz means that the vulnerable field of queer theory has lost one of its crucial theorists at the age of only 46. There is a great hope that his intellectual spirits will live in Queer Theory and that academics and activists will continue working with queer, not only as a rejection of futurity as the meaning of queer critique in the Edelmanian sense but also as a world-making project in the Munozian way as queer culture is under the threath of becoming paradigmatically trivialized as “lifestyle” under the new managerial liberalism.

The intellectual enterprise of Jose Munoz shows us that there are always alternate routes for thinking and living that have no necessary relation to domestic space, to kinship, to the couple form, to property, or to nation. We need to imagine a queer project which supports living that are ”public in the sense of accessible, available to memory, and sustained through collective activity – if we could not concentrate a publicly accessible culture somewhere, we would always be outnumbered and overwhelmed” as Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner have suggested. Without active political imaginations, the sense of isolation among queer people is likely to grow, and ”the lonely pervert” without feeling of community will come back, as Munoz wrote in Cruising Utopia. This would mean diminished expectations for queer life and stands a danger to lead to the undoing of political community.

Muñoz co-edited Pop Out: Queer Warhol (1996) with Jennifer Doyle and Jonathan Flatley and Everynight Life: Culture and Dance in Latin/o America (1997) with Celeste Fraser Delgado. He also edited, together with David L. Eng and Judith Halberstam a special volume of Social Text, “What’s Queer about Queer Studies Now?” (nr. 84/85; 2005).

See also Celeste Fraser Delgado remembering José Esteban Muñoz