This post is part of our Encountering Precarities series. The thematic thread engages with the multiple and asymmetrical forms of precarisation and vulnerabilisation involving both ethnographers and their interlocutors in and beyond the field.

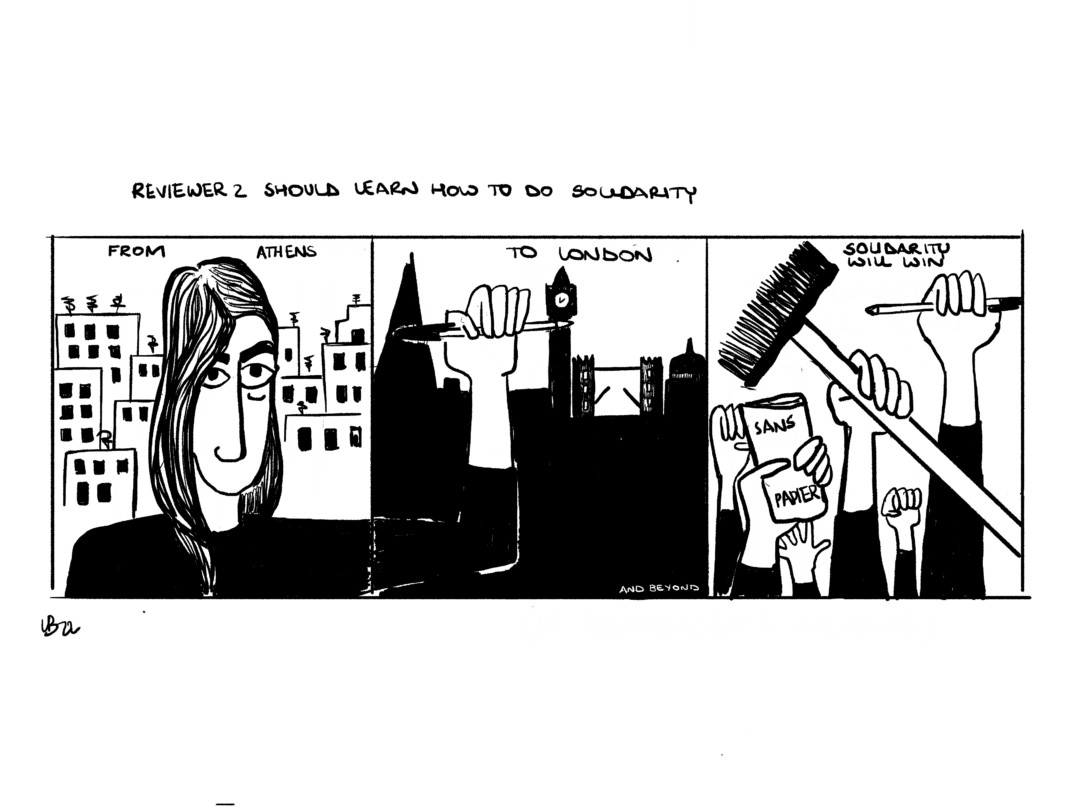

I begin this reflection on the potential of solidarities in anthropological praxis with an example drawn from the University College Union (UCU) pension strikes in the U.K. In 2018, many PhD researchers, including myself, stood in solidarity with tenured academics striking against pension cuts at University College London (UCL), even if our bank accounts resembled more those of the institution’s cleaners who were also protesting for better working conditions at the time, than of our lecturers, hinting towards potential grounds for shared solidarities. Still, our academic solidarity did not simply align with the dream of tenure; instead, we collectively infused picket-line discussions with other political issues affecting the academy, and pushed for more direct representation of teaching assistants (TAs) and precarious academic workers. Standing in solidarity became a spatiotemporal ‘bridge’ (Rakopoulos 2016) that connected us across the academic hierarchy, through processes of horizontal reciprocity that fostered engaged relationality. As teach-outs proliferated, academic authority gradually dissolved and the picket line became a temporary autonomous zone (Bey 1985) of discursive equality. Our failure to connect with the parallel struggle of outsourced workers back then, was partially mitigated when a zero-hour contract migrant cleaner spoke of her experience of precarity within the institution during one of the PhD researcher-led seminars. The response was overwhelmingly positive, with many saying ‘now that we know, we cannot turn our gaze away from these exploitable working conditions’. Alongside opposition to new proposed pension cuts, the 2022 UCU strikes also demanded an end to race, gender, and disability pay injustices, and the elimination of insecure contracts. While this does not directly affect subcontracted workers, it is a nudge in the right direction. In November, UCU publicly criticised UCL’s use of agency workers to replace striking outsourced security staff, followed by a co-coordinated national day of action on February. Making connections and building solidarities across the institution is a slow and continuous process, but remains indispensable for an inclusive and sustainable academic practice.

Standing in solidarity became a spatiotemporal ‘bridge’ that connected us across the academic hierarchy, through processes of horizontal reciprocity that fostered engaged relationality.

When I came across Viola and Olivia’s call on the challenges and opportunities of shared precarities in the field, I had not yet read EASA’s report on academic precarity (Fotta et al. 2020). I had recently completed fieldwork in a ‘home’ context in the south of the Global North, and intended to focus solely on the ‘leap’ between the experience of fieldwork as an embodied, deeply invested practice, affected by political and economic changes that shape the social experience of both research interlocutors and researchers, and the academic setting where analysis takes place that systematically denies these interconnections. I was researching migrant political self-organisation in Exarcheia, my native neighbourhood in Athens, tucked between one of the centre’s most affluent areas and affordable downtown neighbourhoods inhabited by various migrant communities. The neighbourhood has a long history of political resistance, and of experimentation with anti-racist communal conviviality and self-organisation. It played a central role in the solidarity care movement that developed in Greece during the economic crisis to counteract the social effects of austerity and the shrinking welfare state, and subsequently in the refugee solidarity movement, housing thousands of people no longer on the move in self-organised housing squats.

My immersion in the field had been slow and gradual, since by 2018 hordes of researchers had visited the self-organised communities for short or long-term study, not always leaving behind a good name for themselves, or for anthropology. I heard stories of researchers taking the residents’ name registry from the refugee/migrant squat they were conducting participant observation in, while the researcher positionality itself raised questions on who controls the narrative and whom the critical analysis would ultimately benefit. Apart from researchers, since the refugee reception crisis escalated in 2015, Greece has seen a large number of volunteers, journalists, humanitarians, and ‘good-willing’ people passing through (Papataxiarchis 2016a) following their ‘need to help’ (Malkki 2015). The fact that I was thanked by a long-term refugee and solidarian[i] upon returning to the neighbourhood after the end of fieldwork, made me reflect on how socially extractivist some of these short-term engagements might have felt in the context of overlapping crises, echoing Heath Cabot’s criticism of anthropology’s ‘crisis-chasing’ tendencies. She argues that by valuing crisis, the discipline can invoke logics endemic to humanitarian intervention that replicate epistemic and explicit forms of violence (2019:5). How differently, however, might we approach research on crises if we were to de-exceptionalise them, by recognising that the setting of academic production itself is in crisis, our own lives are affected by the same dynamics that (re)produce the crises we observe, and that we can collectively learn from them to challenge their effects?

Upon arriving in the field, I flagged my research positionality as a sign of ethical honesty, whilst downplaying previous social and personal connections to the neighbourhood that could act as social capital coercing people into participating, believing that my role as researcher demanded some sort of objective distance. As fieldwork continued, I was invited to political assemblies organising resistance against the eviction of recognised refugees from UNHCR-funded flats, and to refugee housing squat assemblies where residents collectively managed the running of their living spaces. When crisis becomes the norm, providing care is often a habitual response, as is collective organisation against increasing systemic hostility dispossessing people of social and political rights. By the end of my fieldwork, the Greek state unleashed a violent attack on migrant/refugee and other political spaces in an attempt to curb resistance in the neighbourhood, and pave the way for its gentrification. I was held at gunpoint during a police eviction operation, saw my neighbours’ communities being uprooted, and simultaneously my ability to afford living in my native neighbourhood slipping further away. Reporting on the violence and offering legal, emotional, and material support to those most affected, became a moral duty as a citizen, neighbour, friend and researcher, thus blurring the lines I had tried to draw for the sake of ‘objectivity’. Beyond compassion and empathy, the emotions commonly cited in literature (Fassin 2012, Muehlebach 2012) for motivating social engagement against dispossession, moral action in the field often stemmed from the recognition that we had to protect each other from the violence that we collectively, albeit unevenly, experienced, drawing from shared understandings of justice and horizontal solidarity.

Us and ‘them’: The ‘schism’ of the young academic

It was in similar contexts of engaged solidarity, where alternative forms of collective organisation were imagined and performed, and many of my most significant observations on the effects of systemic violence emerged. Refugee interlocutors would often challenge my cultural relativism after participating in solidarity assemblies together, ask me about my position on feminism and disclose their own. These settings allowed us to reflect on our respective positionalities, discuss differences, and create common ground. When I attempted to write about these conversations, I was told that the work is about ‘them’. However, the reflexive agency of my migrant interlocutors – who in questioning me often questioned entire anthropological constructs – would be lost if our dynamic dialectic of mutual recognition (Panourgia, 2019:231) was left out of the thickness of ethnographic description. As would any attempts to speak of the ‘thick’ solidarities formed in the field that tried not to gloss over difference (Liu and Shange 2018:190), and the shared knowledge generated through these exchanges, along with its social potentiality. Having come full circle in my initial quest for distanced objectivity, I felt that these moments of contact and co-creation with their inevitable messiness, power inequalities, and struggles provided a unique ethnographic framework for collective reflection and future action, alongside my original research documenting increasing border hostility within the southern European capital through growing exclusions and negations of refugee and migrant rights.

Having come full circle in my initial quest for distanced objectivity, I felt that these moments of contact and co-creation with their inevitable messiness, power inequalities, and struggles provided a unique ethnographic framework for collective reflection and future action.

While struggles for the freedom of movement dominated my fieldsite, migrants and locals also organised together against precarious housing and working conditions, which affected both. Likewise, academic precarity is not insular, evolving within a framework of increasing neoliberal dispossession that many of our interlocutors know well. The intersectional effects of austerity, tightening bordering regimes, and other political crises, suggest more collective forms of research and resistance in the future. EASA’s report shows that heteronormative white middle-class males remain the least affected by growing academic precarity, while people from working-class backgrounds are being overwhelmingly excluded from the discipline, opening the scope for potential solidarities within and outside the academic sphere. Despite the lack of secure job prospects, only 4% of those surveyed by EASA intended to leave academia within the next five years, while 96% expressed a commitment to advance their careers by accepting temporary part-time jobs, changing workplaces and countries and working a significant amount of overtime; thereby raising calls for care, solidarity, and love to resist increasing competitiveness and alienation (Ivancheva and Keating, 2020:251). Where academics deploy strategies to mitigate precarity by doing whatever necessary to ‘advance their careers’, my interlocutors ‘make do’ in very similar ways, resorting to communal solidarity, political organisation, and the development of care networks. I am not suggesting that these experiences of precarity, punctuated by racialised definitions of legality and illegality and varying intensities of capitalist exploitation, are equable. Rather, that we should move beyond simply observing and writing about contemporary experiences of dispossession that it is assumed we are not affected by, by adopting a ‘detached’ and fictional secure middle-class position, and instead attend to the common threads between the field and the academy.

Anthropology’s tendency not to recognise precarious entanglements amongst researchers and participants rooted in its privileged origins, creates a conceptual gap between the positioned practice of fieldwork and subsequent academic analysis, such that shared dispossessions and thick solidarities that take place in the field are regularly left out of academic writing. Allowing them in might provide analytical and practical insight on how to tackle anthropology’s epistemic crisis. Claims to ‘neutral empiricism’ that tend to over-determine the ethnographic imagination (Jobson 2019:266) are often based on a white, middle class, socially distanced, perspective. In widening its research scope to include ‘women, subjugated and oppressed classes, national minorities, and even marginalized…academic sub-specialities’ (Said 1989:207 in Cabot 2019:262), anthropology can also end up replicating the logics of apartheid and marginalisation it critiques. This point of conjunction where the internal crisis of anthropology meets its epistemological one, as the social attributes of those who are most marginalised and precarious inside the discipline increasingly configure its ‘objects’ of study, calls for a conscious re-direction of our gaze within the academy: who we are, whom we write for, why we write, and ultimately what kind of academia, and social reality, we aspire to.

The transformative potential of solidarity

Papataxiarchis (2016b:209) warns us against romanticising solidarity and sacrificing its semantic variations, while recognising its quasi-analytical status in reference to sociality, engagement and utopia. As a practice, solidarity presupposes relationality beyond narcissistic identification, recognising interconnectedness within a shared social framework as one creates common ground when they stand in solidarity with another. Analysing affective responses to dispossession from the lens of solidarity allows us to identify the critical engagements that people undertake when they try to refashion their lifeworlds (Rakopoulos, 2016:147), enacting visions of who, and how others should be included in them. Reflecting critically with solidarity in academia on who we cite (Allegra Lab 2022), how we relate with our colleagues and research interlocutors, with whom we stand in solidarity and extend affective care, can be a starting point to unpack unequal dynamics and enact the academic space we want to inhabit. Solidarity entails the potential to be transformative and inventive, crafting relations between places and diverse social groups through contact and practices where prejudice can be contested and reworked within frameworks of discursive equality, and new imaginative ways can be collectively conceptualised in relational terms (Featherstone, 2012:3-4). Engagements with contexts that have continuously dealt with precarity through this lens could open up creative dialogues between the field and the discipline on how to research but also how to address crisis.

Reflecting critically with solidarity in academia on who we cite, how we relate with our colleagues and research interlocutors, with whom we stand in solidarity and extend affective care, can be a starting point to unpack unequal dynamics and enact the academic space we want to inhabit.

At the beginning of the refugee reception crisis in Greece, some academics decided to leave their positions in universities abroad to involve themselves in co-creating refugee housing solidarity projects, continuing to engage with academia from this participant position (cf Against the Day: City Plaza: The best hotel in Europe). Others, who decided to decline offers to study at university to participate in long-term border-crossing solidarity, were later accepted in higher education based on the knowledge they had acquired through this engagement, while recognised refugees continue to critically enrich academic projects such as dëcoloиıze hellάş with their hands-on experience of anti-colonial refugee/migrant struggles taking place in squares and refugee camps around Athens. Beyond direct crossovers and overlaps, organising struggles through collective decision making in horizontal assemblies, often taking place inside university campuses, which until recently have been protected from police intervention under the sanctuary law, allowed people from diverse social, ethnic, academic and professional backgrounds and legal statuses to come together to discuss and act towards the society they envisioned. While arguments and disagreements were not uncommon, thinking through the solidarity lens on the root causes of dispossession and injustice affecting us in multiple ways, led to inclusive communities of mutual support that produced synthetic views of social experience as the base for collective action. As we got to learn from each other and to see from each other’s eyes, we also learned, and sometimes failed, to centre more pressing temporalities. Action deriving from these collective processes, ranged from supporting evicted refugee protests for housing to co-organising protests against humanitarian evictions supporting wider demands for the right to housing, defending public space from far right take overs, running education projects, collective social kitchens and pay-if-you-can falafel shops, and hygiene support networks spanning across Athens to both mainland and island camps during lockdown. It was always outward-looking, coupled with disseminating social critique through multilingual communiques, posters and banners, and in temporary museums, talks, poetry readings, public performances and feasts. Relating with each other in this engaged way, we made sociopolitical kin. Extending care from covering immediate needs to promoting rights and defending the right to the city supported social existence in the present as a possibility for future kin making.

In troubling, precarious times, the academic task could also entail ‘mak[ing] kin in lines of learning to live and die well with each other in a thick present’ (Haraway 2016:1). Solidarity, understood as a thinking-and-acting with, can facilitate multiple forms of politicised kin making amongst different forms of labour inside the institution, across academic spaces, society and, equally important, the more-than-human. As participant-observers, and as a community that is increasingly experiencing precarity, we have the possibility to explore solidarity’s potential both as praxis and analytics, in its varying manifestations. It might not save us from the exploitative nature of capitalism, lest we decide to collectively dismantle it, nor immediately reverse the effects of short-term contracts. By recognising and writing about entangled experiences of precarity and discrimination and the multiple solidarities that take place inside and outside of the field, however, we can produce thicker descriptions of contemporary social experience and bridge the epistemological and internal crisis of anthropology, which find themselves closely intertwined.

[i] Vernacular translation of the gendered Greek term allileggya/o/s denoting someone who is engaged in political solidarity and/or in horizontal care. It has been used increasingly in recent years as a result of external interest in solidarity in the Greek context, and of the large number of people coming to Greece to engage in solidarity work adopting the term, instead of the more neutral activist or volunteer.

Bibliography

Allegra Lab Editorial. February 2022. ‘On the use and abuse of networks in academia‘. Allegra Lab.

Bey, Hakim (Peter Lamborn Wilson). 1985. T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. Autonomedia: New York.

Cabot, H. 2019. ‘‘The business of anthropology and the European refugee regime’’, American Ethnologist, 46(3), pp. 1-15.

Fassin, D. 2012. Humanitarian reason: A Moral History of the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press

Featherstone, D. 2012. Solidarity: Hidden Histories and Geographies of Internationalism. Zed: London.

Fotta, M., Ivancheva, M., and Pernes, M. 2020. The Anthropological Career in Europe: A Complete Report on the EASA Membership Survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ivancheva, M., Keating, K. 2020. ‘‘Revisiting precarity, with care: Productive and reproductive labour in the era of flexible capitalism’’, Ephemera, 20(4), pp. 251-282.

Jobson, R.C. 2020. The Case for Letting Anthropology Burn: Sociocultural Anthropology in 2019, American Anthropologist, 122, pp. 259-271.

Malkki, L. 2015. The need to help: the domestic arts of international humanitarianism. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Muehlebach, A. 2012. The moral neoliberal: Welfare and citizenship in Italy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fassin, D. 2012. Humanitarian reason: A Moral History of the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press

Kotronaki, L., Lafazani, O., Maniatis, G., Messandra, S. ‘‘Against the Day: City Plaza: The best hotel in Europe’’, South Atlantic Quarterly, 117:4.

Liu, R., Shange, S. 2018. “Toward Thick Solidarity: Theorizing Empathy in Social Justice Movements”, Radical History Review, 131, pp. 189-198.

Panourgia, N. 2019. ‘‘Recognition: Exarcheia, mon amour’’, Journal of Greek media & culture 5(2), pp. 231-249.

Papataxiarchis, E. 2016a. ‘‘‘Being there”: At the front line of the ‘European refugee crisis’- Part 1’’. Anthropology Today, 32(2), pp. 5–9.

Papataxiarchis, E. 2016b. ‘‘Unwrapping solidarity? Society reborn in austerity’’. Social Anthropology, 24 (2), pp.205–210.

Rakopoulos, T. 2016. ‘‘Solidarity: the egalitarian tensions of a bridge-concept’’, Social Anthropology, 24(2), pp.142-151.

Said, E. W. 1989. “Representing the Colonized: Anthropology’s Interlocutors”, Critical Inquiry 15(2), pp. 205–25.

Featured image by Letizia Bonanno.