‘At home,’ we are in full command of the dialectics of knowledge and recognition.

Jean Améry, “How Much Home Does a Person Need?” (1966: 47)Thus we may reason as follows—’There is smoke; there is never smoke without fire; hence there has been fire.’ Yet smoke is not the cause of fire but the effect of it.

Charles Sanders Peirce, “Grounds of Validity of the Laws of Logic” (1991: 95)

Where there’s smoke there’s fire?

Monday, July 23, the light changed suddenly outside my window in Athens: a dirty, yellowish tinge colored the pale buildings opposite my balcony. Wondering what was going on, my partner and I went up onto the roof to find that the familiar summer blue sky, punctuated by soft clouds, had been obscured by a sulfurous haze traveling from beyond one of the surrounding mountains.

Fire? He hypothesized, alarmed.

Fire was certainly a good guess. Almost every year there are wildfires in Greece, some closer to Athens than others. Just a few years ago (2015) we watched as airplanes circled our beloved mountain of Ymittos dumping tons of water to stifle the encroaching blaze—clearly visible from a high perch we found in the city center. We had walked our dog through the wildflowers on Ymittos all that spring, but fire left the green trails, pines, and cypresses a charred bald mess. I have not returned there but once since then. Except for the church at the base of the mountain that remained undamaged, with its lush internal gardens, the whole mountainside had become unrecognizable.

Or 11 years ago: when I took the bus through the Peloponnese to Kalamata, after the horrific fires of 2007 destroyed olive groves, villages, and houses, killing 84 people, many of them elderly people in their village homes. My mouth hung open alongside other passengers as we passed through kilometers and kilometers of burned countryside: as if the rolling hills had been turned inside out to expose the land of the dead.

But for some reason, this time, we shook our heads. And just like others we spoke with throughout the afternoon, we somehow decided that what looked like smoke must be what Athenians tend to call “the dust from Africa:” the wind carrying the desert sand all the way across the Mediterranean basin, bringing an uncanny light to the city and spilling a thin layer of dust, necessitating new cycles of mopping. We walked to the city center in the strange yellow-red light, as wild winds turned potted plants upside down and pulled fig trees into the street. What is going on? People asked.

“Dust from Africa” seemed to be the consensus.

The fires (for they were, in fact, fires …) had moved as fast as that wild wind—faster than news could travel, at least by mouth. Within a half hour, the village of Mati, just outside Athens, where one of my friends grew up, was “no longer recognizable as a settlement anymore,” in a quote that has been repeated often in the newspaper since. As the sky over Athens began to clear, and the wind calmed, only later did we check the news to learn that droves of people had been forced into the sea, or stuck on the highway owing to the worst fires to rip through Greece since 2007. People had burned in groups of families, friends, and strangers. Hundreds lost their homes.

Tragedies and Solidarities

The following day I visited one of my recent fieldsites, the Social Pharmacy of Vyronas, located in a separate municipality just outside the Athens city center. There, people draw on the theory and practice of solidarity to collect and redistribute medicines, at no cost, to those who need them: Greeks and non-Greeks; pensioners, refugees, long-term migrants (Bonanno Dissertation in process; Cabot 2016; Teloni and Adam 2013). Along with other “solidarity initiatives” such extra-state, grass-roots responses are a key way in which residents of Greece have dealt with the economic difficulties following the debt crisis and the ongoing devastation of austerity (Loukakis 2018; Rakopoulos 2014; Rakopoulos 2016; Rozakou 2016; Rozakou 2018; Theodossopoulos 2016).

Those who assist at the Vyronas social pharmacy are a chatty and generous bunch, though they face their own difficulties with money, work, family, health, and otherwise. And yet, through the daily work of sorting and redistributing medicines, they offer assistance and also—in the words of one of my interlocutors— “pass their time,” finding purpose and sociability.

We discussed the horror of the stories that had been surfacing:

Mati was like a contemporary Pompei.

People had drowned in the sea seeking protection; they had also drowned from the smoke.

A group of twenty-six people had burned embracing one another, in some cases making it impossible to tell bodies apart.

And then we discussed the political aspects of this “natural” disaster:

The suspicion (and now certainty) that a fire this bad cannot have been accidental.

That the government had yet again failed to protect the people: How could people have been left to drown in the sea? Why had the coastguard or rescue boats not come for them (though they had saved many in the nearby port of Rafina, and Egyptian fishermen saved numerous people stuck in the sea)? Meanwhile, the poor response had also been linked to austerity: there had been 30% cuts in the state’s fire-fighting capacity, and people had not been able to maintain their properties in ways that would ameliorate fire, owing to ongoing financial difficulties. And finally, there was the inaccessibility of escape routes owing to years of unregulated development, which trapped hundreds on the highway seeking to flee the fires, leaving some to die in the charred skeletons of their cars.

We also discussed the solidarities: That locals and foreign tourists (Germans and Danes and Dutch) had also been working in the rescue effort. That municipal collection centers have had to make a plea to people to STOP SENDING SUPPLIES—so many have rallied to respond to the need in the wake of the fires.

And finally, we collectively expressed surprise and even shame at how each of us had assumed that the uncanny light in the city was simply “dust from Africa,” while fires raged just down the coast.

“Greece is burning”

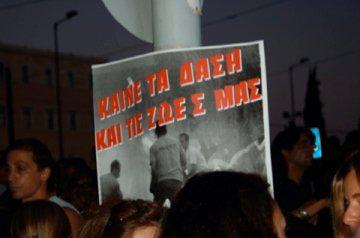

Against the backdrop of such fires, “Greece is burning” has often been used as a kind of metaphor for the political and economic ferments that have rocked the country since even before the debt crisis and the onset of austerity. Particularly when cited by Greeks themselves, “burning” often seems to signify what many characterize as a failure of the state to protect its people. In the massive protests following the 2007 fires, “they burn our forests and our lives” resonated as a cry against what many saw as the poor response of the state to keep the fires under control and rescue victims.

In these latest fires—some of the largest casualties any country has suffered in forest fires in the last hundred hears—structural and political-economic factors (combined with climate change, arson, and strong winds) seem to have produced the perfect crucible for the Attic coast to burn.

But the “burning” of Greece extends beyond forest fires. In 2008, the massive protests against the shooting, by a police officer, of fifteen year old Alexandros Grigoropoulos, led to the burning of banks in the city center by certain groups of protesters (and the deaths of four workers); as well as, of course, the violent response of police (Dalakoglou and Vradis 2011). In 2011, fascist attacks against migrants constituted what the press called out-and-out “pogroms” (Cheliotis 2013). In 2013, the killing of anti-Fascist rapper Pavlos

Fyssas was met not just with outrage and disorientation by many citizens on the Left, but also with speculation that many members of the police were in collusion with the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn. Such revelations highlighted, yet again, how Greece was “burning:” how many saw the state apparatus as not just irresponsible but perhaps actively enacting violence on its citizens.

After Alexis Tsipras of the Syriza Coalition was elected in 2015, amid an atmosphere of rising hope among much of the population, the re-imposition of austerity—despite the referendum of July 5, 2015, in which the vast majority of Greeks voted “no” to austerity measures—led again to extensive unrest, as well as a glaring mistrust of the state that has resurfaced and, for many, remained. Protests following the referendum were marked by the usual tear gas and Molotov cocktails—another instance of the “burning” of Greece. Now, as Greece leaves “the troika,” incessant discussions in the international press in Mid-August, 2018, focus on the instability that will now face the country as it strikes out “on its own,” so to speak.

These 2018 fires are thus the latest and most dramatic example of the ongoing precaritization of a populace that increasingly does not recognize itself “at home,” and which has (in the view of many) been left “to burn” by the state—and also by Europe.

Selves and Others

From my safe position in Athens (uninformed as I was), the consensus that what hung over the city was “dust from Africa” is telling. The alien haze was assumed to come from somewhere else: not unlike the over-a-million seekers of refuge who have passed through Greece since 2015.

It was not unreasonable to interpret the uncanny light in Athens that day as “dust from Africa,” as it has been a particularly heavy season of “African Dust” this year in Greece. News coverage sometimes describes the African dust in terms of “waves” (like waves on the sea, or “waves” of migration). Health warnings highlight the respiratory risks, and how dust (like smoke, like water) can “drown” those who breathe it. But this time, that alien fog indexed the horror of a burning village just down the coast, where many Athenians go to the sea on hot summer weekends.

As Charles Sanders Peirce noted long ago, where there is smoke there is usually fire. Smoke is my standard classroom “go to” example of indexicality: a sign that necessarily points to the attendant causal (if not always visibly present) reality of fire. In this case, however, the smoke—misread as dust from Africa—has since come to index also the failure of the state to fulfill its protective role; and a failure of Europe, which, through austerity, has demanded absurd cuts in the state’s protective capacities—the winnowing away of the state’s “Left Hand” (Bourdieu 1999).

Since doing research in Greece in the context of austerity, I have had to learn to think differently about displacement. In my earlier work, an ethnographic study of asylum in Greece (Cabot 2014), I focused on the legal processes affecting refugees and asylum seekers and the role of human rights lawyers and humanitarian workers in responding to their predicaments. At the end of the book (written in 2013) I hypothesized that with the debt crisis and austerity the meaning of citizenship—and understandings of the relationship between self and other—might be changing even more dramatically. But I had not, at that time, fully comprehended how the Greece of today would so radically alter the way both I and my field interlocutors drew the line between insiders and outsiders.

The displacements of hundreds and maybe thousands by the fire speak to an overarching context in which the shape of the socio-political body in Greece has radically changed. The dominant liberal vision of European citizenship—in which citizens are entitled to civil rights, and non-citizens (or “aliens”) must claim and seek human rights—no longer seems to apply on Europe’s margins.

At the social pharmacies, diverse categories of people—some who have crossed national borders, others of whom may have only moved from their home villages to Athens many years ago—have had to negotiate often urgent forms of need. Basic “rights” such as shelter, food, medicine—not to mention civil rights such as education and pensions—have been thrown, for various populations in Greece, deeply into question. As such, so-called “regular Greeks” have often sought assistance at diverse extra-state initiatives (grassroots networks, as well as formal humanitarian organizations like Médecins du Monde and Médecins Sans Frontieres); alongside people who, not so long ago, might have been clearly marked as “others:” migrants and refugees, the chronically poor, and addicts.

Indeed, Medicins’ Sans Frontieres—not just the Greek state—has now set up a major intervention in the aftermath of the fires in Mati.

Among my field interlocutors, I have heard new accounts of the relationship between Greeks and “foreigners.” Such accounts attest to how categories of mobile and more sedentary populations, “migrants” and “citizens,” have become increasingly unclear—both to scholars and interlocutors themselves—in ongoing contexts of precaritization. [1] In 2015-16, I heard the frequent sentiment that because Greeks have experienced displacement themselves throughout their modern and contemporary history (specifically via the 1923 population exchange), they are particularly well-equipped to assist newly arrived refugees. Or that Greeks during the crisis have become “internal refugees,” and so their struggles and interests overlap with those of recent arrivals. Of course, there are also narratives that redraw the boundaries of the ethnos even more robustly: that Greeks have been abandoned by their state—why should refugees receive housing, food, and a stipend? Or as I heard repeatedly in Lesvos this past summer, many locals on the island (which became an international symbol not just of the refugee crisis but of local solidarity with refugees) resent not just new arrivals, but the foreign humanitarian organizations and workers who have taken on such a powerful and interventionist presence in the Aegean. Recent fascist attacks attest to the unstable and shifting “mood” that indexes relationships between self and other (Borneman and Ghassem-Fachandi 2017).

The Uncanny

Last summer I met with a friend who has been living and working in elsewhere in Europe for the past few years. He seeks to mobilize Greeks who, like him, have had to leave to find work elsewhere (an enormous outmigration that has accompanied austerity). He helps to organize shipments of pharmaceuticals from other European countries to numerous social pharmacies within Greece.

He mused that when he comes back to Athens to see his family he experiences a feeling of ανοίκειο.

This is a word I had never heard in all my years in Greece, so we looked it up: the uncanny. He explained that he no longer really recognizes the city where he grew up; and yet, it remains strangely familiar. Panoramas and encounters (of and with public space, objects, persons, practices) seem simultaneously utterly transformed and ineluctably the same.

Ανοικειο references the German unheimlich which, as Bettina Stoetzer (2014) highlights in her work on public space in Berlin, connotes both “being without a home” and Freud’s description of being unable to trust one’s senses. The uncanny thus captures affective, sensual, and psychic aspects of displacement. Jean Améry (1980) , in his exquisite essay “How Much Home Does a Person Need?” locates the experience of displacement in an incapacity to “read the signs” and decipher them correctly (47). He tells the story of how, having fled the Holocaust, he encounters an SS officer in Belgium who addresses him in his local dialect; he is moved by the irrational desire to unveil himself, to answer in the same dialect—even though he knows this would mean imprisonment and even death. But he moves on, and swallows that yearning for the home that has become strange and even hostile.

Displacement, as I am learning to understand it in contemporary Athens, is never complete. It entails twists and turns: moments of shock and surprise that the displaced (the persecuted, the burned, who fled into the sea) were actually very much at “home,” as well as the slow accretion of experiences that turn one’s home and homeland inside out. Displacement speaks not just of the loss of a home across national borders but also of the uncanny: that home that has become unfamiliar or even hostile. The police officer who might kill or threaten you, the government that does not protect you, the uncertainty about whether and how to trust one’s senses or read the signs. An Attic village and popular spot for swimming has become the land of the dead. Dust from Africa—a displacing wind that itself calls up the Mediterranean’s own long history as a sea of displacements—is in fact a fire burning just over the hills.

Works Cited

Améry, Jean. 1980. At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and its Realities. S. Rosenfeld and S. P. Rosenfeld, transl. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Anderson, Bridget. 2017. Keynote address: “Troubling Migration?”. In IMER: International Migration and Etniska Relationer. Örebro, Sweden.

Bonanno, Letizia. Dissertation in process. Pharmaceutical Redemption: reconfigurations of care in austerity – ridden Athens. University of Manchester.

Borneman, John, and Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi. 2017. The concept of Stimmung: From indifference to xenophobia in Germany’s refugee crisis. Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7(3):105-135.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1999. Acts of Resistance: Against the Tyranny of the Market. New York, New York: The New Press.

Cabot, Heath. 2014. On the doorstep of Europe : asylum and citizenship in Greece. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Cabot, Heath. 2016. Contagious solidarity: reconfiguring care and citizenship in Greece’s social clinics. Social Anthropology 24(2):152-166.

Cheliotis, Leonidas. 2013. Behind the veil of philoxenia: The politics of immigration detention in Greece. European Journal of Criminology 10(6):725-745.

Dahinden, Janine. 2016. A plea for the ‘de-migranticization’of research on migration and integration. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39(13):2207-2225.

Dalakoglou, Dimitris, and Antonis Vradis. 2011. Spatial legacies of December and the right to the city. Revolt and crisis in Greece:77-88.

Isin, Engin. 2018. Mobile peoples: Transversal configurations. Social Inclusion 6(1):115-123.

Loukakis, Angelos. 2018. Not Just Solidarity Providers. Investigating the Political Dimension of Alternative Action Organisations (AAOs) during the Economic Crisis in Greece. PArtecipazione e COnflitto 11(1):12-37.

Nieswand, Boris, and Heike Drotbohm. 2014. Einleitung: Die reflexive Wende in der Migrationsforschung. In Kultur, Gesellschaft, Migration. Pp. 1-37: Springer.

Rakopoulos, Theodoros. 2014. The crisis seen from below, within, and against: from solidarity economy to food distribution cooperatives in Greece. Dialectical Anthropology 38:189-207.

Rakopoulos, Theodoros. 2016. Solidarity: the egalitarian tensions of a bridge concept. Social Anthropology 24(2):142-151.

Rozakou, Katerina. 2016. Socialities of solidarity: revisiting the gift taboo in times of crises. Social Anthropology 24(2):185-199.

Rozakou, Katerina.2018. Από «αγάπη» και «αλληλεγγύη»: Εθελοντική εργασία με πρόσφυγες στην Αθήνα του πρώιμου 21ου αιώνα [From “Love” and “Solidarity:” Voluntary work with refugees in early 21st centure Athens. Athens: Alexandria.

Stoetzer, Bettina. 2014. A path through the woods: remediating affective landscapes in documentary asylum worlds. Transit, 9(2).

Teloni, Dimitra-Dora, and Sofia Adam. 2013. Solidarity Clinics and social work in the era of crisis in Greece. International Social Work:0020872816660604.

Theodossopoulos, Dimitrios. 2016. Philanthropy or solidarity? Ethical dilemmas about humanitarianism in crisis afflicted Greece. Social Anthropology 24(2):167-184.

[1] I, like other scholars, would suggest that in fact this distinction has always been fluid and, in many ways arbitrary (Anderson 2017; Dahinden 2016; Isin 2018; Nieswand and Drotbohm 2014). Yet how interlocutors and scholars themselves understand what these categories connote tends to change according to social and political-economic context.