Reflections on the EASA Conference at the University of Milano-Bicocca, 20-23 July, 2016 : “Anthropological legacies and human futures”

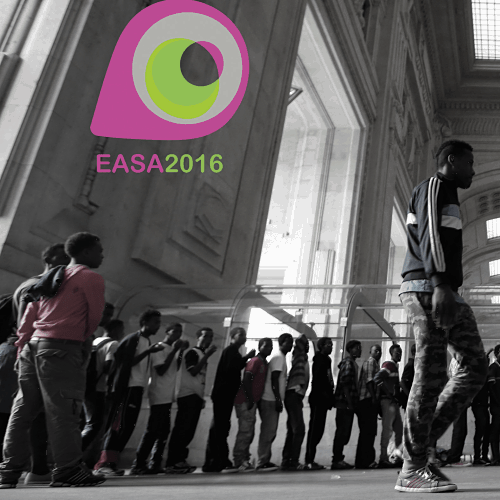

It was the last day of the 14th biannual conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA). On that very last conference day, before leaving the conference space, the Milano-Bicocca university, I queued for wine at the front of the Pluto Press reception with other anthropologists. Until the final moment of the conference, in the wine queue, I continued to ponder about the message of the conference visuals – the conference poster in particular. A black and white photograph with shades of light colors depicted young black men lining up in a queue inside a massive concrete building. The black men were portrayed as if they were waiting for something. The space depicted in the photograph reminded me of the Central Station in Milan where I have changed trains countless times on my way to Florence, but I could not tell for sure.

I wondered whether the conference poster, portraying black bodies, tried to do the work of institutional polishing (Ahmed 2015) and transform the otherwise white space inhabited by anthropologists into a more diverse space. Did it try to compensate for the whiteness of the wine queue?

Yet, perhaps my attempt to guess the physical location of the queue and the queue’s purpose is less important. Perhaps the poster just tried to transmit the message that the photograph could have been taken “anywhere”, or that the black men could be waiting for anything. Or, perhaps they waited for nothing.

The broad conference title of the 14th EASA biennale, “Anthropological legacies and human futures”, did not help the viewer to make sense of the poster’s representation. Anthropologists have left traces in many places and if we apply our current temporality, humans everywhere are supposed to have a “future” – hopeful or gloomy, always judged from the standpoint of the observer. Future in their mind, humans queue for many things, they wait for tickets at railway station counters, in banks for money transfers, in summer sales for reduced bargains and in bars for wine. Whether it is the black men on the EASA conference poster or the anthropologists at the EASA conference, human beings make calculations before they decide to use their time queueing. What do I gain? Is it worth waiting?

While I speculated about the purpose of the conference poster’s queue, my queuing at the “Anthropological legacies and human futures conference” had a destination – Italian Wine. One of the conference’s afternoon activities, the Young Scholars’ Forum was running late, which, I assumed, was the reason why the afternoon wine was served late and a queue was forming at the front of the conference’s pop-up bar. Unlike my queuing at the conference, it is unlikely that the black men’s queuing in the EASA conference poster was incentivized by wine. The perception, that makes the production of the conference visuals possible, does not establish an association that would relate the poster’s queue to wine. This perception is shaped by histories of reading the “other” and those histories are shaped by racism (Ahmed 2004, 31). Was it not in apartheid South Africa where black men and people of color produced wine (and still do) for the consumption of white men? And as I was told many times during my visit to the vineries of the university town Stellenbosch in Western Cape, the majority of South Africa’s black men still (sic) do not share the white men’s wine culture.

Since my first academic conference in Turkey’s Mediterranean town of Mersin in 2013, a port city where thousands of Syrian refugees sought shelter from war – or queued for a human future, I have been pondering about the practice of wine-drinking among us scholars. At EASA in Milan events with ‘wine’ received a special mention in the conference program: ‘wine served.’ As many times in other spaces before, I was fascinated by the gravitational force of that mention. In my PhD research in Egypt, I registered a similar mention bestowing exclusivity on high society events. A vineyard in the proximity of Cairo sold wine to a select group of people using an imagery of Egypt’s golden past while creating walls around its premises that those who lacked the financial, cultural, and social capital would not cross. In the conference space, I asked myself what wine sipping while gazing at the EASA visuals says about us scholars, anthropologists or aspiring anthropologists. Whom do our practices include and whom do they exclude? Do we reflect on our own activities? Do we sometimes ask what kind of barriers they create?

Unlike the black men’s aimless queue depicted on the EASA poster, the young scholars wine queue was in a constant movement – those who had arrived early did not have to wait long to enjoy free wine. Moreover, fairness was guaranteed for the anthropologists. Their queue functioned according to the principle of “first come first served”. Later that day I learned that the black men’s queue did not function according to the same principle as the anthropologists’ queue. We had to leave the conference wine for those who had patiently waited longer than us and run to Milano Centrale, the station I imagined was depicted in the conference poster, to catch our train to Switzerland. We navigated our way through the railway station to the new glass doors that separate the platforms from the rest of the railway station. We passed through a check point, the new barriers preventing those strangers who do not possess a valid ticket from causing terror at the platforms, and made it on time to our train.

The train to Basel was unusually crowded for a Saturday evening. It was packed with vacationer families as one could tell from the sleeping bags, camping mats, bicycles, lunchboxes and the many children who undertook the train journey with their parents. Nothing would beat the moment when the lunch boxes could be unpacked while watching the summerly landscapes pass by.

Amidst the holiday crowd, we could not but be curious about two young boys, much younger than the black men in the EASA poster, moving nervously back and forth in the train carriage. We wondered whether they had not found their seats and where their parents where. Eventually they found their place next to some other young boys and the journey began; for the vacationers, conference participants and the two small boys.

The journey to the last Italian city before the border with Switzerland takes about two hours. It is always there where the power of the sovereign state exercises its right to decide who is allowed to enter the beautiful mountain country. This was the moment when “the first come first served” principle of the EASA conference’s wine queue ceased to apply and the destiny of the EASA’s conference poster’s ‘black men’s queue’ was laid bare. A destiny that is defined by principles of white racist Europe that seeks to expel all those bodies that it defines as a problem. As so many times before when I have travelled this route, it was in the Italian city Domodossola where the men dressed in blue uniforms entered the train and the doors were locked. There is no way out of the train beyond that point until the men (and sometimes women) in uniforms have searched the train.

Scattered throughout the train, the police were after the skin color of the men from the EASA poster. While no-one asked me for my documents, the two boys who just a few moments earlier had showed their tickets to the controller, were removed from their seats. Even though they tried hard to appear invisible when encountering the representatives of the Swiss state, behave like other passengers and enjoy the journey without the lunchboxes of the other children, what mattered was their skin color. The unwelcomed passengers, including a crying baby in a woman’s lap, were summoned to one intersection of the train carriages. The black men’s queue of the EASA poster began to form in the middle of the train corridor.

The operation was completed before we arrived in the Swiss winter athletes’ paradise, the city of Brig, so that the exit from the train could follow smoothly. We and the queue of black men got off the train and the families with lunchboxes continued their journey. Or as Sara Ahmed (2000, 52) has put it earlier, the freely moving and acting white subjects could continue their journey after “expelling those other beings”, the strangers.

The silence in the train demonstrated how “legality” surpasses moral concerns: We like the rest of the travelers did not do anything to stop the operation that was based on racial profiling.

Our minds are familiar with the images of the practice that unfolded in the train, even though we might never have encountered it in person. Newspapers print images from the shores of Italy, or the ‘French ghettos’, what was the name again? “The jungle”. The EASA poster and a photo exhibition decorating my own host institution’s walls at the time of writing this essay reproduce these images for us scholars to view. We have become familiarized with such images.

In a desperate attempt to document the sadness or as a pretentious act to fool myself that I was doing “something”, I indiscernibly tried to film the convoy – the black men of the EASA poster with their families, escorted by the police until one of the police officers forced me to erase the pictures and my films and shouted that “next time you have to pay 2000 Swiss francs”. This is what we anthropologists are used to, we ask permission from the people we photograph and then we worry about issues related to copyright. I believe these regulations hold for the EASA poster decorating the corridors of the Milano Bicocca University as well.

The black men were returned to their place in the EASA poster – to their place in the queue. That queue is normally out of my sight – if I do not specifically search for it. And so again I did not have to do anything for it to disappear from my sight. I wondered whether the black men would again appear in the next EASA conference poster and contemplated about writing something on “the preservation of whiteness and wine culture”.

Two years have passed and EASA15 is approaching. Drawing on the apparent inequality that is reflected in the disparity between scholars lining up for wine and the queue represented on the poster (and materialized on the train to Basel), we wonder how next week’s EASA conference “Staying, Moving, Settling” will live up to one of the most cherished self-characterizations of anthropology – the engagement with the diversity of human life? How do we locate these two queues in next week’s conference?

EASA goers of 2018: Do we continue to visualize others non-movement while discussing our own mobility over wine?

With special gratitude for their critical remarks to Bogumila Hall, Julie Billaud, Miia Halme-Tuomisaari and Shaahed Tayob.

Ahmed, Sara. 2000. Strange Encounters: embodied others in post-coloniality. London: Routledge.

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Collective Feelings. Or, The Impressions Left by Others.” Theory, Culture and Society 21 (2):25-42.

Ahmed, Sara. 2015. Living a Feminist Life. Durham and London: Duke University Press.