For people immersed in bureaucratic institutions, like universities, the current ruckus over HAU raises at least one longstanding anthropological question: what kinds of organizational structures not only allow certain types of behavior but even allow these to be repeated over and over again? And here I don’t simply mean: “when is someone allowed to repeatedly behave badly,” but also “when is someone allowed to repeatedly behave well?” This question underlies people’s concerns around the kind of oversight that existed at HAU but also underlies people’s praise because the journal managed to contribute to productive intellectual dialogues time and time again. With this in mind, I want to write without condemning anyone. Instead, I appeal to readers’ anthropologically grounded curiosity about social organization as I discuss what I know about how HAU was structured before its transfer to University of Chicago Press.

How do I know what I know? I was on the HAU monograph board (2014-2017) and an associate editor at the journal (2016-2017). But more importantly, I was one of three people who agreed to run the journal as a team while Giovanni da Col took a six-month leave in 2016. The transition process was rocky, and I stepped down before I could fully take on the shared responsibility of interim editor-in-chief, but continued as an associate editor. But during this process I talked to staff members, read the HAU constitution carefully, and afterward continued talking to staff members and various people involved in HAU’s organization. I was never involved in the day to day running of HAU, and so some of what I describe below may be inaccurate regarding the actual practice, although staff have read a draft of this and confirmed my account.

HAU was not run the ways that other scholarly journals I have been involved with are run. Yes, HAU had a constitution, and several boards associated with it; yet, to understand the internal distribution of labor, it helps to understand the open access software platform HAU uses, Open Journals Systems, which encourages but does not determine a certain way of organizing a journal. To be clear, social organization is more important than the interactions implied in the platform, but it helps to understand what the platform suggests.

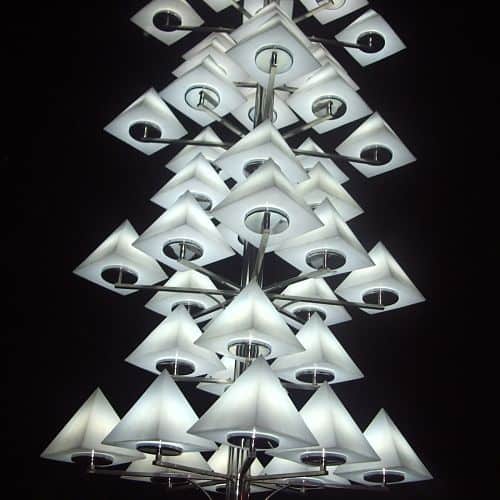

The journal was run as a pyramid of labor, which intriguingly enough reflects the social organization imagined by OJS, which is the most popular open access software freely available.

Jason Baird Jackson, a colleague at IU, editor of the journal Museum Anthropology Review and fellow commentator in this series, explained to me (after my tenure at HAU) how OJS works, based on his own editorial experience. OJS is a platform that was initially designed not only with very large journals in mind, but was also supposed to facilitate scaling up quickly from a smallish journal to a mammoth journal. It is a platform that could easily run a journal like Nature or Science, if that is desired, with thousands of contributors and many moving parts. It is built to allow a great many people to donate (or get paid for) labor. It can have one or many editors, section editors, and a huge number of other internal roles. The idea of different people with different roles is fundamental to the platform. In a small operation, one person can assume several roles, but that person must wear different (software) hats for each role. The platform also creates logical flows between tasks and people based on common norms already present in many journals. But like all platforms, OJS (especially the version that precedes the latest release) coaxes users down paths built into the software, especially by reminding users constantly that the journal could get bigger.

There are consequences to using a platform like this. It is designed to be a pyramid of labor, based on the assumption that many people will be willing to give a tiny bit of free labor, and other people will be willing to devote larger chunks of time, but may only be willing to do so sporadically. To address the quandary this poses for running an organization, it encourages cells: small labor collectives of people tackling one or two tasks, such as copy-editing a special section, or finding reviewers for a set of articles, with a few other people coordinating these tasks. All these cells are overseen by the editor-in-chief, and perhaps a handful of other people – the top of the pyramid can be a plateau instead of a peak. The higher you go up in the pyramid, the more you can see of other people’s labor below you, but usually you can only see the segment of the triangle below you (you are at the top of a mini-pyramid within the overarching pyramid). Indeed, the only person who really has access to all moving parts and is able to coordinate everything is at the top of the pyramid. While the software could be adjusted so that this concentration of control is ameliorated, at HAU, the editor-in-chief was the only one who knew about all the moving parts, and who clearly invested social labor into ensuring that this remained the case. The platform’s organizational suggestions were also supplemented by HAU’s constitution and what little I know secondhand about the University of Chicago Press’s agreement with HAU, which proposed that the editor-in-chief was also envisioned as editor-for-life, with only one unlikely and complicated mechanism in place for removing the editor-in-chief being mentioned in HAU’s founding document.

This of course could potentially be mitigated by having in-person or virtual meetings; indeed, all associate editors could theoretically meet and communicate beyond the OJS platform. This was not the case with HAU. All communication within the journal was funneled through the editor-in-chief. The different pockets of labor never coordinated with each other. Associate editors neither consulted with each other about how to handle a set of reviews, nor discussed about other concerns that came up in running the journal. The faculty board of HAU monographs never met to discuss book proposals, and indeed only made a decision at the front end, voting by individually assigning numbers to each book proposal to determine which projects should be pursued. After the manuscripts were reviewed, we never met to discuss the reviews and whether the book should be published. Any attempts to change this system were dissipated, and perhaps quite reasonably. After all, changing this system would have created more work for participants, and as academics, we try to minimize service work whenever possible. What is important to note is that while HAU regularly had parties at conferences, there were no institutional moments in which the boards as a whole were coming together to discuss running the journal. And as far as I know, there weren’t actually many long-standing members who worked steadily together – except for the staff. The left hand truly never knew what the right hand was doing, indeed the fingers on the hands didn’t coordinate often with each other either.

This meant that it was possible for associate editors (who were mainly tenured anthropologists) to have only minimal contact with the HAU staff (who were mainly graduate students at far-flung institutions), say, a brief email exchange about finding reviewers for an article. The editorial boards, to the best of my knowledge, never had any contact with the staff, who were all under the purview of the editor-in-chief. Should social problems arise at any stage in the publishing process, there was no institutionalized process for dealing with these problems.

To repeat, all of this was made possible by the software-aided division of labor, but also the typical ways in which academics approach service work of this nature. In my experience, we engage the service tasks directly in front of us, often as quickly as possible, and ask few questions unless we are physically in a meeting together.

We have too little time: the academic life means juggling many obligations, and so we tend to accept institutional processes already in place instead of questioning them.

Scholars often find it boring and thankless (as indeed it often is) to get involved in running their institutions and associations. We often even encourage others to minimize the time they devote to institutional maintenance. This, of course, may be a rational response when those institutions are less and less committed to the individuals within them. Yet possibly as a result of this relationship to service, not many people knew how HAU was actually run, even those people prominently associated with HAU. This is the social consequence when a pyramid of labor occurs within the constraints of our contemporary academic lives.

There are two other aspects that I personally find useful for understanding how HAU functioned.

First, HAU’s temporal rhythms were crisis-driven, much like the temporal rhythms of classroom teaching or many projects in contemporary capitalist workplaces. HAU would present authors and staff with challenging deadlines, commonly presented as an emergency situation in which all hands were needed on deck. This seems to have happened for every issue. And when you are living in periods of crisis, punctuated by periods of recovery in which you have time to deal with the other demands that were brewing in the background while you were in crisis mode, you are less likely to engage critically with the processes that created the ‘crisis’ in the first place.

Second, the editor-in-chief is assumed to remain editor-for-life. There is no expectation of a transition written into the HAU constitution, and no HAU board has the right to replace the editor-in-chief. This speaks to the nature of workplaces in which people tend to stay in the same career for life. Many academics are used to having to live with colleagues who behave in ways we wish they wouldn’t, and realize we have to deal with them for the rest of our working lives.

We develop skills for tolerating less than desirable behavior.

I have been suggesting that HAU was possible because relatively new technologies allowed for new participant structures, and many of the academics involved were applying older models of how journals are typically run and what sort of practices institutional oversight enables (and/or prevents). It might sound like I am asking for institutional oversight, but this, as Sara Ahmed has pointed out so elegantly, is a double-edged sword. What if the current uproar about HAU is precisely because it lacked the institutional oversight that typically buries problems created by people who have been engaged in community exchanges and institutional norms because they have been part of an institution and part of an academic community for a number of years?

In HAU’s case, a newness carved out of older forms became possible, allowing for both good and bad in less familiar packages. At the same time, it was hard to know who knew what in the process – did associate editors know what staff experiences were like at the journal? Or even what authors’ experiences publishing with the journal was like? Did the chair of the advisory board know? I personally believe that there were serious problems in how the staff were treated, but I was never sure myself who knew and what solutions were being attempted. Some people knew there were problems (not always the same problems!), but didn’t always know the extent of the problems, and found it hard to confer with each other, and extremely difficult to assemble information even when they tried. And so I lived, very unwillingly I might add, one of the dilemmas that I find myself reiterating about new media all the time: new participant structures dramatically change in unexpected ways how knowledge circulates and how it leads to action; yet everyone involved can still think things are going on pretty much as normally as they ever do.

It is extremely helpful for understanding and reflecting on the crisis under discussion, and “what we do” more generally. Thank you.

Absolutely fabulous—thank you so much for this, Ilana!

very nice article, but on the wider insinuations of the trappings of the semi-informal and platform enabled centralisation, am i the only one who sees the elephant? which graduate student or academic hasn’t shuffled papers (which is not cooking the books) to request the maximum amount of drip-fed reimbursements as provided by established university institutions like travel funds or libraries, in order to then shift these moneys into perennially underfunded and unsupported but important activities and investments of the research endeavour.

This is the open-secret, research as real praxis with a few tactics up its sleeve. i hope we can start talking about that to.

There is no real ideal of oversight, it would crush a lot of momentum, no one expects non-buerocratic forms of venture organisation to voluntarily subject themselves to tediousness.

Aspects of this are the result of structural underfunding severely affecting the academic publishing industry and the games we play (not me!) in our corners of the post-fordist economic hustle.

The accounting: its unclear to me why anyone working for a voluntary association part time while being funded at graduate school at an open access niche venture was pretending to expect to rely on the entirely nominal honorarium for financial stability, honorariums for publishing start-ups like these are rarely more than four figures per year, this could not have been used to get by, or even make a dent, depending on which city one lives in.

didn’t we all catch the medialens shitstorm too? see https://www.jonathan-cook.n… on the pernicious effect of the corporate defence of salaried journalist and their hierarchical models? lets posit something radical and necessary to transform the entire ecosystem, crowdfunding, micropayments, basic income etc “We are in a time of transition. New technologies offer new ways to carry out both investigations and journalism” and research.

I am a software developer with the Public Knowledge Project, where I work on a later iteration of the Open Journal Systems software that HAU runs. (I do not comment on behalf of PKP.)

I want to thank you for your insight into the experience of running a journal on our platform, and the ways in which the roles system contributed to the siloing of editorial and managerial staff. It is a welcome spotlight on how technical solutions bear down on social relations.

I also want to reinforce the picture you paint of (most) academics’ relationship to service work, and flesh out a little bit how that comes back into decisions about the software’s structure. Most of the feature requests that reach us on the development team involve ways of minimising editorial “exposure”: preventing them from being notified or made aware of anything they don’t absolutely need to do right at that moment, and getting them in-and-out of the system as quickly as possible when they do need to do something.

Much of this is just good tool design — help people do stuff with minimal fuss. But as you rightly point out, when that structure is deployed to isolate editorial labour from managerial labour, or when it actively encourages that isolation, it can be counterproductive. We are always caught between serving the scholarly publishing community as-is and building a platform to serve what we want it to be.

Since joining PKP, I’ve only worked on OJS 3, a ground-up rebuild of the v2 software that I believe HAU is using. As such, I can’t speak specifically to the roles system in OJS 2, but the current version has a more flexible roles and workflow system, largely inspired by frustration over the forced structure of older versions. That, however, puts the burden back on the journal. There’s no escaping the need for an important conversation at every journal regarding what the role structure should be, who is providing oversight, and who is taking responsibility.

One thing that’s become clear to me is that there is no such thing as a “typical” journal workflow. More public discussion like what you’ve provided may not necessarily align practices everywhere, but it can help make these structures more intentional. And that, in turn, will help us build better software.

I agree, it is possible to use OJS productively for decades without ethical harm to anyone, it all depends on the social organization that accompanies the platform.

I am so glad that you wrote this comment, and hope that people reading my blogpost will also read what you say. I tried so hard in my discussion not to blame OJS for how this journal was run. People can take an affordance in a technology and do something with it that no designer could ever anticipate. As an anthropologist, I normally delight when I see this happen, because it proves that people are more imaginative than one could ever predict. Not this time.

I didn’t read it as an attack on OJS. I think the mutually constitutive dynamic of what you describe came through clearly. I shared it with our team and we really enjoyed it. If all discussion of our software was as thought-provoking and carefully considered, we’d be very lucky. In fact, we _need_ more reflexive conversations like this.

Thanks Nate. Thanks @pkp! Since you and your colleagues are following some of the current discussion, here is a #hautalk use case to note in this context.

I know I am not the strongest OJS user (despite my love for it) but I think I have this right. In the current disciplinary effort to make sense of HAU and its dynamics there is interest in what we might call “historical mastheads.” In print publishing, one could, if needed, always go to an old paper issue to see who all the people involved in a journal were in a given moment. When a modern digital journal publishes whole issues with old-school look and feel (PDFs with pagination, etc.) they can sometimes present their print or print-like masthead and provide the same service, but the OJS default is to present item level content with item level metadata but not to present the current-but-soon-to-be-historical journal level metadata. Put more simply, you can look at an old article but you cannot generally know who the editorial board, etc. was at the time the article appeared. The only ways around this (and I will start using them myself) are to publish a masthead in the issue (or alongside any content release) or to create historical data on the masthead or with a supplementary (linked) page. Used without thinking about these dynamics in the ordinary way, OJS erases the historical masthead with whatever the latest one is. (Right?) This is made worse if it (as with HAU, it seems to me) cannot be fished out of the Internet Archive. Unless it were published, it also would not be captured preservation efforts focused on content and its metadata. I welcome your thoughts.

This seems super wonky to talk about, but anyone trying to assess, for instance how many scholars of color or women were involved in a journal in a particular moment would want to access the historical masthead of a journal. When someone says that they were removed from the masthead in a controversial moment, how can we find documentary evidence of this? If one wanted to consult with past staff or participants in a journal, how would one know who they were? In general, masthead listings are how people prove, when questioned, the role that they filled at any given moment.

Maybe there are existing techniques in OJS for this issue. I will keep exploring it, but #hautalk has made me much more mindful of the need to address this historical function.

You raise an important problem and one we’ve discussed but not addressed (yet). I am mindful of the concerns raised by some that #hautalk is sucking in tangential subjects and losing focus on the original accusations of abuse. To avoid taking focus from this discussion, I’d invite you to open this issue on the PKP Community Forum. You can tag me there (@NateWr) to get my attention. Or if you prefer a more neutral forum I’m on twitter under the same handle.

This is a really interesting and informative thoughtful take. I do want to say that I am a co-editor of an open access journal (Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research) that is run on OJS and it is a system that has worked smoothly and enabled our work practices — which is running the journal as a basically editorial collective with no editor in chief and one Managing Editor who handles the bulk of administrative issues. We have weekly Skype meetings and a listserv where all decisions are discussed until we reach consensus. So while of course in an STS kind of way, the logic of the material (or digital) infrastructure can thwart or amplify certain kinds of organizational practices I just wanted to offer a non – hypothetical example to footnote the caveat in this piece that interface is not destiny.

This is a sharp and important – and properly anthropological – response to a many-layered crisis. I suspect, though, that differently positioned actors could write an alternative account of the pyramid, based on other kinds of interaction, including those parties at conferences and, perhaps most important, gaggles of men drinking together in bars.

It also highlights some deep contradictions in our attitude to formality. Academic life is full of “difficult” colleagues, and most often we find work-arounds to accommodate often very problematic behaviour. Hierarchical imbalances don’t help, but even peer-to-peer confrontation can easily create quite explosive situations. The decision to move a problem into a formal register requires a lot of bravery, even in institutional settings where procedures and support are available. Where they’re not available it’s obviously even worse. But anthropologists’ self-perception as loose and unbounded folk who don’t “do” formality doesn’t always help when unboundedness starts to hurt other people.

Ilana’s eloquent and insightful comments on academic pyramids resonated deeply with me. Though I have not experienced the inner workings of the HAU pyramids, her comments on ‘service overstretch’ and the tendency within bureaucracies of scale to veer towards selective (in)visibility speak to all of us working within contemporary bureaucracies. Nevertheless, there was an itch for me too in reading Ilana’s piece, at least as it relates to the particular revelations around HAU’s editorial working practices.

Focusing on the institutional and digital systems that allowed the parcelling of tasks and the elimination of oversight brackets off the organisational culture that let a pyramid become a pyramid, an Editor become an Editor-in-Chief, prospectively, for life, or to let bullying pass unchecked as the price to pay for getting this big and beautiful thing off the ground. This is not about our journal interfaces (as Ilana points out, OJS could have a plateau at the top; it could also allow for rotation), or even about the difficulties of formalising an initially informal project that was running on enthusiasm and hard work, but about recognisably social dynamics that are also a mirror of our discipline and that allowed a pyramid to become catastrophically top-heavy: the power of patronage, of favours, of name-dropping, of prestige-through-proximity, of endorsement through association. As ethnographies of pyramid-schemes have shown, after all, such schemes thrive on enchantment: on the excitement of participation in this social thing; on the promise of future rewards, on the belief that it must be OK behind the scenes because, well, why could so many people be wrong?

In this respect, calls not to focus on ‘personality’ miss the point. Because HAU was fundamentally a charismatic project in which the institution became inseparable from the person of the EiC-for-life. This, too, should give us pause, because, like the cell-culture that Ilana describes, this tendency to trade in the politics of personality and charisma-by-association is endemic to our field: it is engrained in our casual vocabularies of expertise (‘A-list academics’, ‘elite departments’, ‘rising stars’), but also in the politics of citation, of invitation, of hiring, of publishing; of the valorization of certain kinds of scholarly practice (capital-T Theory) over others; the privileging of certain centres of knowledge production over others. The working practices of HAU need to be *independently scrutinised, yes (and urgently, too, if the project is to survive). But we also need to take this as a moment to bring our tools of critique to our own academic communities and the forms of scholarly patronage that they reproduce.

Madeleine’s comment brilliantly expands what was already an illuminating argument, precisely by setting out the other kinds of pyramid we may discern through the current murk. The invocation of ‘enchantment’ captures a very important and central dimension of what has happened (and explains why those who refuse to be disenchanted insist all complaints are simple expressions of ‘jealousy’).

I agree with Madeleine – HAU seems to have been not only a pyramid of labour, but of charisma and finance too: one in which people believed in the system because so many big names were on its covers; one in which the initial fundraising became a role model for many other departments to follow suit, as they saw it as the ticket for the wider salvation that HAU promised to be. It is in this sense that HAU was a pyramid scheme. It has been a field of brilliant and ground-breaking ideas (I think), but also a rather in-house game in favour of the elite, a place whose key figures – some of whom are now guiding the protest – published 5-6 articles each in as many years, as if that was a normal practice and not a gift of hierarchy and privilege.

I would add that the charisma was not merely GDC’s, but derived from a sense of his connection to higher powers in the discipline. As we learn from Graeber’s and others’ revelations, people were often belittled by GDC saying: what would Graeber say to this? What would Wagner and Sahlins say to this? In this sense GDC enchanted like a disciplinary cargo movement leader, professing his connection to anthropological gods (some of whom were, ironically, writing about the stranger king principle in a HAU publication). Not sure how else to explain that stars accepted to work for a journal edited by somebody not having a PhD, which was a fact known for years. He gave the sound, they gave the words.

Secondly, I think that the focus on precarity and predation that Allegra and others rushed to underline, has to be balanced with a clear sense of what people got, or were promised to get, by turning a blind eye when participating in HAU. Yes, the system fed on precarious situation of young scholars, but – does one who is truly falling through the cracks volunteer their work for an academic journal? Or do they do it in hope of boosting their CVs? Don’t get me wrong, the latter is in the function of the former, of course, but the extent to which precarity is used as an unreflected explanation in the academia astonishes me. The system promised and presumably, gave many (im)material rewards – association and prestige that Reeves describes – and I imagine it was this that was the key to many complicities, high and low. Patronage gives and takes in both directions, and no simplified narrative about the ‘exploited’ workers, or heroic calls for expelling the bully, will be enough to redeem us from the wider field of dependency and complicity that just transpired.

just a couple of points to this interesting discussion:

1) While I think both Ilana’s and Nate’s comments suggest, the software is not the problem, we seem to forget that each and every aspect of our work these days gets automated: In classrooms, lectures and materials are put online, teaching via digital tools increasingly in blended/online-only formats; feedback is on forums increasingly not facilitated by the faculty who design and teach the class; and some teaching is outsourced; and a lot of teaching is also outsourced, sometimes to tutors subcontracted by companies. In research our communication is mostly on skype, not only in big transnational projects, but also people who work across a corridor hold skype meetings online because we are ‘too busy’; processes of paper submission and feedback are automated – to save ‘time’ and make the process ‘anonymous’ (whereas specialisations are so narrow and you can google the title of the paper and see its author in the matter of seconds); and we end up in systems and systems of hot-desks, call centers, email communication and what not just to ‘give us more time’… which in this case, we see, has clearly backfired. So this whole debacle really calls for the reassessment of the degree to which we can allow an automation of the anthropological and academic profession. Sure, everybody is busy, but the fact that a big list of people who gave their names to this journal, never came together face-to-face in this capacity in some on- or offline format to discuss the issues at stake, is quite frightening and telling.

2) While I agree with Madeleine and Ivan that we should speak more about the hidden pleasures of self-exploitation and charisma-by-association in search of career progression routes, I think using this as a reason to say ‘let’s focus back on the toxic personality’ makes little sense. Without the normalised structures of knowledge production that feed off free work and self-exploitation to sustain academia, this guy couldn’t have taken and exploited the HAU opportunity for seven years with absolute and total impunity! So yes, his case has to be audited, but so do many others that are happening in our own workplaces while we’re speaking. And especially those in structurally secure position (“we’re all precarious”, I know the trope, but some are much more vulnerable than others…) have to intervene, take a stance, challenge both individual predators and predatory structures. But from what I see, most colleagues are remaining complacent, be it because they are ‘too busy’, or because they are closing ranks and washing their hands to protect departments and sub-disciplines.

This is terrific — it looks to the infrastructure but not in a determinist way, but rather at the interaction of several structural, cultural, institutional components. Terrific as a stand alone analysis and really helpful for the #hautalk conversation.