Ethnography and Political Engagement

This Thematic Thread emerged from a workshop organised (online) at the LSE in February 2021, entitled “In the moment and after the fact: Ethnographic reflections on political engagement”. The aim of the workshop was to investigate how moments of collective action and rupture are experienced and understood, and what is made of them in their aftermath. We wished to reflect on the ways in which popular movements and collective organising continue to be generative of political experiments and imaginaries, and how these moments reverberate in more long-term projects. It brought together ethnographers from across anthropology, sociology, performance studies, and political science, working in South America, Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and South and South-East Asia. We were struck by the urgency with which certain themes constantly reappeared in our different field-sites, collaborative practices, and in our discussions across the workshop. What became evident by the time of our last roundtable was a desire to explore these exchanges further through collectively written pieces, which we are now sharing as this week-long series of posts. This introduction will draw out some of the main topics that emerged both during the workshop and as part of our collective writing endeavour, which we hope will open up further conversations with others wrestling with similar questions.

Defiance and Opposition

Across the various regions in which we work, we found ourselves discussing how rising authoritarianism, identity politics, and counterrevolutionary times shape political and ethnographic possibility, particularly when there is a commitment, on the part of researchers and their interlocutors (here, activists), to defy the broader political context. From Erdogan’s constitutional power-grab in Turkey, to rising neo-fascism in Greece, with revolution turning into civil war in Syria, and repressive tendencies on the rise from the UK to Ecuador – often exposed and exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic – what do ethnographic and political engagements look like when the political tide flows against them ? On such topics activist and academic thinking alike can lapse into melancholy or determinism, or perhaps fall back onto the view that carving out a living in the margins is the best that can be attained. What was notable from our conversations was that working in close proximity with political movements and with individuals crafting corners of liveability in oppressive contexts provides ethnographers, whatever their discipline, with a particular access to the hopes, aspirations, and creative capacity alive in collective social and political action. Our long-term engagements mean that the story does not begin and end with a certain political event or movement cycle; rather, we try to understand what might continue – thus disrupting binary understandings of movements as resulting in either success or failure. As we explore in the first post in this series, Defiant Engagements, defiance can rather be understood as puncturing small holes into a wide canvas, through both quotidian acts and more explicitly political gatherings around specific endeavours.

Chronological time does not constitute the backdrop upon which we tell the story, then, but rather becomes the medium through which political meaning, capacity, and possibility are enacted.

The temporalisations of political events and their flow are not taken for granted by movement participants. The creation of (or combatting against) the production of a moment in time as particularly “momentous”, or as understood as being part of a longer trajectory of struggle, are political projects in and of themselves, ones that often clash with how commentators of various sorts would mark them. As this series’ second post Punctuation and Flow shows, things can look very different indeed when we focus on temporalising as a political problem (for our interlocutors) and an ethnographic problem (for us). In the post we focus on how certain moments of heightened political engagement amplify the flow of any movement, and how interpretations of their significance emerge and become contested in their aftermath. Questions surrounding “punctuation” and “rupture” enable the defining of political events, but also have implications for our ethnographic engagements and analysis. Chronological time does not constitute the backdrop upon which we tell the story, then, but rather becomes the medium through which political meaning, capacity, and possibility are enacted.

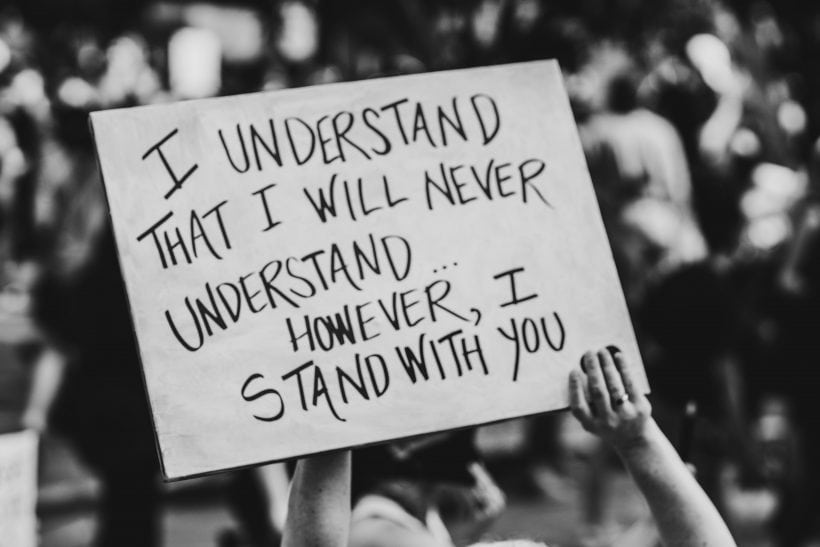

Photo by Zoe VandeWater on Unsplash

Sometimes there is a great sense of finality to an action or movement cycle, as identified by activists and participants themselves. From our examples, we might point to the 2017 constitutional referendum in Turkey, which ended (in that particular form) for activists with the “yes” vote winning, or the election in Greece of the right-wing party New Democracy in June 2019, whose support for investment in a mine in Northern Greece ultimately foreclosed local residents’ hopes to sabotage it. Then again, with reference to some other of our collective research settings, how else to account for the return to the streets in Thailand or Kashmir, or the forms of solidarity organising we have seen in the aftermath of the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Sheikh Jarrah (East Jerusalem), or the electoral successes in Chile, where against all predictions the people elected a constitutional assembly composed largely of leftist independent candidates? Bleakness can always be found, but so too can things working out – all successful mobilisations are built on the back of defeats, setbacks, seemingly-mortal wounds. Put slightly differently: activism fails, until it succeeds. Determining the beginnings and endings of movements, and their successes and failures, is never straightforward, nor can this temporal bracketing and merit-evaluation ever avoid political motivations and effects. As engaged ethnographers, we need an ability to account for this as part of reflecting on political engagement. Both ethically and politically, we feel compelled to adopt an affirmative ethnographic stance that takes seriously the myriad ways in which violence, difficulties and failures make up political struggles while also highlighting the potentialities and political imaginaries that these enact and give rise to. This sentiment permeates our ethnographic engagements and our collective writing.

Bleakness can always be found, but so too can things working out – all successful mobilisations are built on the back of defeats, setbacks, seemingly-mortal wounds.

What remains, in one form or another

Our two following posts explore critical affirmation as an activist and research approach in tandem with what those engaged in political movements do with the past in the present for the future. We found ourselves reflecting on the resources made use of in political engagements and, leading on from this, to the material and immaterial production that routinely takes shape in such spaces. Here are just a few examples of both, taken directly from the broader pool of ethnographic cases that animated our workshop discussions. Material production: a cage built in effort to make visitors sympathise with the predicament of the inhabitants of a marginalised Turkish Cypriot village; Scottish National Party activists prefiguring an independent Scotland by creating new banknotes; Tunisian fishermen crafting multi-lingual banners to hang on their boats in protest against the docking of an anti-migrant European fascist boat. Immaterial production: solidarity networks mobilising against evictions and Bedouin village destruction in the Naqab (Palestine/Israel); the Kaleidos research team’s production of a collaborative digital platform to track violent deaths in Ecuador; the co-creation of soundwalks with Filipino migrant workers making their presences, personal trajectories, and collective organising visible in London and Beirut; collective archiving projects aimed at tracing and salvaging a history of mobilising among a migrant population plagued by incarceration and deportation in Lebanon.

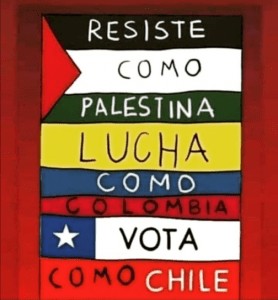

To make sense of what remains, we turned to the modalities and conditions of possibility for what has come before to relate to what comes next. As the discussion in our third post Artefacts and Repertoires shows, material traces are sometimes tended to – curated, even – by political movements for future action, while at other times they are destroyed during an action, either by creators themselves or by their opponents. But materiality is not the only thing that (can) remain, with a performative, embodied “repertoire” being a key avenue of knowledge transmission and network building.This immaterial production has transnational repercussions as tactics, discourses and practices travel across space and borders to nurture new ideas and practices, not only in our ethnographic way of thinking about political struggles, but also in other movements. The transnational nature of anti-establishment movements is acknowledged by activists. To give just one current example, witness the sharing of tactics, with attendant material production, in placards from Colombia urging “Resiste como Palestina, lucha como Colombia, vota como Chile” (Resist like Palestine, fight like Colombia, vote like Chile). What remains is always unstable and never predetermined, and can give birth to new modes of acting, seeing and engaging with the political in all its forms, including, for instance, the writing of ethnography.

Photo by authors

Staying with material and immaterial production, we were struck in our collective conversations by the manifold things that actors do with what remains to construct compelling narratives: it is about the story that is told, how different elements can be brought together, how people can feel part of a longer history of struggle and a wide network of like-minded people. How, then, are those involved in collective political action crafting, using, and relating to “facts” and “evidence” in order to pursue their political aims, often in the midst of competing “truths” and evidence-making projects (driven by governments, the police, parties)? In our fourth post, Facts and Evidence, we complicate the politics of evidence making by offering examples of relatively successful and unsuccessful attempts to constitute evidence for particular political ends and demands. Together, they offer an entry point for understanding the ethnographic entanglements behind “truth making” in our various contexts, and how these processes are deeply intertwined with the social, political, and economic instabilities that our interlocutors face. By tracking the contingent relations behind the production of evidence, we illustrate the complexities of building “truths” or “facts” in our various settings.

It is about the story that is told, how different elements can be brought together, how people can feel part of a longer history of struggle and a wide network of like-minded people.

Collaboration(s)

With a view to methodological considerations, we spent some time as a collective trying to think about how to deal with non-presence in the field, particularly in heightened moments of political action. As we discuss in our fifth post, Digital Engagements, there are particular frustrations and anxieties associated with “not being there” when flash points occur — protests, evictions, revolutions and uprisings — especially if one has been a long-term participant observer. Like many others since the Covid-19 pandemic began we reflected on the possibilities and shortcomings of digital ethnography, but with particular reference to political engagement: what is made visible or invisible, exaggerated or understated online. There are lessons to be learned here from activists, particularly bearing in mind the hierarchies and inequalities involved in the division of labour and diversity of roles between those on the ground and those who are not. Media, communication and press can (and often can only) be done away from the “frontline” and the immediacy of having to tend to other more urgent tasks, and coordinating actions are often better done far away from rapid censorship, surveillance and network cuts. These are necessary collaborations between actors with different positions in relation to the engagement, each with roles to play. The ethnographer’s role in these contexts can and should be negotiated as part of these broader considerations.

Questions surrounding collaborative endeavours become all the more salient in times of restricted international mobility. What is more, even when there is not a pandemic occurring, being there can be impossible. In Algeria, for instance, foreign academics were not allowed a visa to enter the country during the 2019-20 Hirak protest movement, while more generally it is challenging for scholars from the Global South to obtain visa access to carry out fieldwork in the Global North. Political engagements therefore have a way of practically engaging the different levels of “presence” and “remoteness” involved in working collaboratively and politically towards shared goals. Rather than solely reckoning with the new post-Covid moment, these can force us to learn from grassroots mobilising to think collaboratively about the different possible parts of “research” and “engagement” and the problematic aspects of these endeavours that need to be refuted and opposed.

Thinking about ethnographic engagements and the material conditions and division of labour involved in collective political action is also another way of considering an age-old problem for anthropologists: that of “giving back”.Here we simply suggest that political involvement with one’s interlocutors offers a particular valence to these reflections, a direction and directedness to what can be done, through examples of providing advocacy avenues and specific technical capacities, or being co-involved at different stages of movements and amplifying messages. Explicitly collaborative projects with our interlocutors were also part and parcel of many of our research practices. Developing more responsive forms of scholarship that directly relate local realities to global struggles ranged from the creation of soundwalks, archives, online databases, theatre performances, and visual stimuli for collective experiments and imaginations. In keeping with our affirmative but critical approach, the discussion of such projects in the closing section on Collaboration and Creativity does not shy away from their pitfalls and difficulties, but does gesture towards what possibilities they open up, nevertheless.

Thinking about ethnographic engagements and the material conditions and division of labour involved in collective political action is also another way of considering an age-old problem for anthropologists: that of “giving back”.

What also arose from our collective thinking and writing is the open-ended and questioning tonality of this week’s six posts. Our pieces draw on specific ethnographic examples, but are themselves a collective processing of this material, thereby forcing us to do justice to particular situations while drawing out their broader significance. As the reader will hopefully intuit, the ethnographic material brims with collaboration among those involved in long-term political commitments and more punctuated actions to create openings. Indeed, political engagements are almost always wilful, collaborative projects of one sort or another – they require people to come together in pursuit of something. Sometimes this is explicit in the form of collective actions and endeavours, with different groups coming together in solidarity, and producing something new from there. Sometimes it is less explicit, but is there regardless through slow, daily acts of care. In conveying our thoughts in a collective voice, we strove to preserve the uniqueness of particular struggles whilst highlighting the importance of thinking and writing together as a political endeavour in and of itself, one that perhaps defies those institutional and academic limitations imposing and valuing more individualistic modes of knowledge production. In the current political moment, then, take this collective writing project as an attempt to think our intellectual aspirations through the prism of our political engagements.

In conveying our thoughts in a collective voice, we strove to preserve the uniqueness of particular struggles whilst highlighting the importance of thinking and writing together as a political endeavour in and of itself.

Featured Image by Dan Meyers on Unsplash