In May 2024, following a barrage of Russian missile attacks on power stations across Ukraine, Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal announced that citizens had to expect wide spread black outs. He also urged Ukrainians to limit their electricity consumption and announced that energy supply for medical institutions, schools and public services had to be decentralized. The government would, according to Shmyhal, support people in improving their immediate energy needs through solar panels and heat pumps while increasing natural gas production.

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion in Ukraine in 2022, official statements and media reports on infrastructure have been omnipresent. But what exactly is infrastructure and why does it matter? According to scholars of infrastructure working across multi-disciplinary environments from technical professions to the social sciences, infrastructures can be conceptualized as networks that link up the built environment, people and technology. They might include energy, transport or communication, whilst also relating to natural resources, human sociality and other species. From this perspective, such infrastructural networks often remain invisible when they function as planned yet suddenly appear in the public imagination when they fail, get destroyed or become subject to spectacular political projects. Over the past few years, people who live in Ukraine have massively suffered from and been lethally affected by the breakdown of these networks. At the same time, continental and global infrastructural connectivity has been re-shaped by the war. Many Europeans have bitterly realized that the mundane foundations of cheap light, warmth and consumption are linked to Russia’s regime of resource extraction and distribution. In turn, the Ukrainian army has begun to target Russia’s refineries to drain funding and fuel for the war.

Continental and global infrastructural connectivity has been re-shaped by the war.

Over the past decades, debates on infrastructure have moved in various directions. Scholars have looked at infrastructure’s expansion across different scales: between global and local, and between different perceptions of time and geographically distributed sites of infrastructure production. In this regard, the past has not been merely a category of academic analysis. It has also been a category of planning practice. Urban planners, engineers and military strategists alike have engaged with the past of infrastructure in tangible and practical ways. Not least in Ukraine, they have selected pasts that they can use – remnants, ruins or contiguous networks – and repurposed them to their ends. While this can entail productive discussions on, for example, Soviet architectural heritage, it might equally give way to sinister calculations. Consider that in the context of the war in Ukraine Russia relentlessly attacks transport hubs in mostly small to mid-sized towns. Aiming to sustain military logistics and the movement of troops alone, lives, housing and the environment become expendable. With the exception of selected transport infrastructure, erasure is often total.

In this article, we – a group of social science oriented urban studies scholars, students and professionals at the Kyiv School of Economics – draw together these different discussions and uses of infrastructure in Ukraine through the lens of material, political and cultural history. While taking seriously the specter of war and its direct connection to the materiality of people’s lives we also aim to broaden the scope. For instance, what can the transformation of monuments tell us about the changing politics of memory? Or how is unequal access to functioning water infrastructure linked to the much longer history of resource extraction in Ukraine? In the following we navigate between these different aspects by lending anthropological and historical nuance to debates on infrastructure as a site of current despair and the possibility of hope for the future.

What can the transformation of monuments tell us about the changing politics of memory? Or how is unequal access to functioning water infrastructure linked to the much longer history of resource extraction in Ukraine?

Infrastructural pasts

In the context of the war, international attention has been strongly focused on the destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure by Russian bombs, missiles and drones. To be sure, there is an existential urgency to this attention, particularly as Russian attacks have substantially disrupted everyday lives and the economy in Ukraine. At the same time, not all infrastructural processes are linked to threats to the country’s critical infrastructure, such as energy, transport and telecommunication. If seen through broader definitions of infrastructure that extend into the realm of memory, politics and emotions, monuments and museums give concrete materiality to reimaginations of the past. In contemporary Ukraine, many monuments and statues are encased in protective structures that shield them from missile attacks and shrapnel from artillery fire. An exception is the gigantic monument of the Batkivshchina-Maty (“Mother Homeland”) in Kyiv, a 102-meter-tall steel statue overlooking the river Dnipro. The monument was constructed in the period between 1978 and 1981. In the Soviet Union, the Batkivshchina-Maty commemorated the Soviet victory over Germany in WWII. The monument in Kyiv is mirrored by a similar statue in Volgograd in Russia and has long been controversial in the context of Ukrainian independence. For many Ukrainians the Batkivshchina-Maty, even though now a landmark of Kyiv, was also reminiscent of the injustices and oppression during the Soviet period. This discrepancy culminated after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 and led to a public debate about memory, urban planning and how to come to terms with the materiality of Soviet legacy.

The Batkivshchina-Maty is a massive monument of steel that is designed to withstand a strong earthquake. From an engineering point of view – not to speak of political divides – dismantling the statue would have been far too technically challenging and costly. Thus, in summer 2023, Ukrainian authorities replaced the Soviet Coat of Arms on the Batkivshchina-Maty with the Ukrainian trident. Turning the monument from a remnant of the Soviet political infrastructure of memory into the statue of a Ukrainian hero woman is part of a broader tendency of transformation. This materially anchored infrastructure is networked with other renderings of the Batkivshchina-Maty that circulate as images and memes on social media. Consider, for instance, the example of a pictured design rendering of the steely statue with the Ukrainian trident destroying Russian drones in the sky above Kyiv.

The Batkivshchina-Maty is one example of how the Soviet infrastructural past reaches into the present, morphing along the way and expanding into new networks of memory and technology. This often uneasy and messy process of building on and transforming Soviet, and sometimes indeed older, legacies of the past is also reflected in urban planning. Towns hosting military bases or related longstanding strategic infrastructures hold a specific position in this regard. An important yet somewhat neglected example is the city of Ochakiv, located at the outlet of the Dnipro and the Black Sea cost. Ochakiv is a historical settlement whose strategic location involved the construction of military fortresses from the Middle Ages. This role has had an impact up until today. The contemporary shape of the city is heavily influenced by its status as a military town hosting a naval base and other military facilities. The post-WWII period has been formative for this and its legacy extends into Ukraine’s present.

In the 2000s, there were attempts to move beyond Ochakiv’s dependency on military infrastructure. At different points in time, there have been plans to establish the city as a recreational town at the Black Sea, leveraging Ochakiv’s location in proximity of pristine beaches and a national park. For many years there have also been discussions around Ochakiv’s deep water port and its redevelopment. In the 2000s investments were made, but the project never went beyond the planning stage and was finally buried when the assets of the main investor, the oligarch Vadym Novinsky, were seized by the Ukrainian government in 2023.

Forming a central pillar of Ochakiv’s economy, its military base is also linked to processes of infrastructural encirclement and delimitation. Public transport is poorly developed in the city and connectivity to other places in southern Ukraine is hampered. Moreover, in the present context of war, military infrastructure – originally conceived of as a marker of security – invokes a lethal threat. Since the full-scale invasion, Ochakiv has been targeted on a daily basis by artillery fire from Russian positions just across the Dnipro. As a result, the city’s population is shrinking. The past of military infrastructure in the city has become an existential threat that is not only driven by continuing destruction, but also by Vladimir Putin’s definition of Ochakiv as a “place of Russian glory.” In this propagandistic view of history, Ochakiv is seen as a part of the Russian core which is, however, currently linked to “NATO infrastructure” that threatens the Black Sea fleet. This military significance, which shapes life in the small city in fundamental ways, connects Ochakiv to the longer history of infrastructure as an encompassing, publicly discussed concept.

The spectre of war

Before infrastructure became a category of analysis employed by scholars in technical professions and the social sciences, it was a term of practice. In the late nineteenth century, French engineers used infrastructure to describe the substrate – the support structure – underneath railway tracks. Travelling from French to other European languages and beyond, it was not until the end of WWII that infrastructure became a widely used term in public discourse. The founding of NATO was linked to that process. In early documents produced by NATO in the 1950s, infrastructure denotes the organization’s network of support structures across different countries that sustained military facilities and operations. At the same time, newly founded institutions like today’s International Monetary Fund and the World Bank catapulted the term into settings of international development. Socialist countries, too, began to take up infrastructure related terminology in the second half of the twentieth century. Thus, throughout the period since WWII, infrastructure has had civilian connotations, but also referred to the sustenance of, protection against and prevention of war.

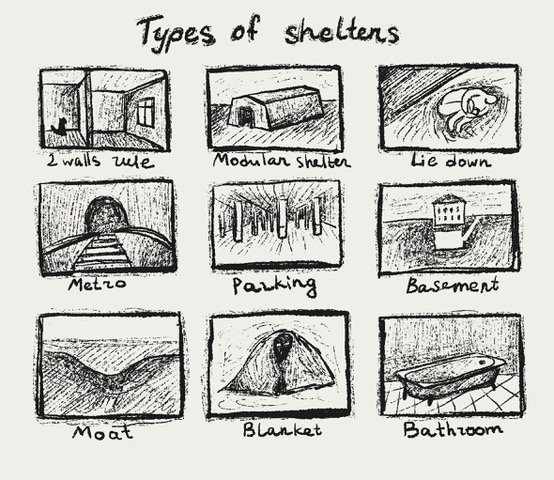

In the context of Russia’s ongoing war of aggression in Ukraine, these multiple meanings have come together in debates on shelters, fortifications and trenches. Today bomb shelters are an essential type of infrastructure in Ukraine, even though internal debates and use do not necessarily correspond with the linear ways in which shelters are envisaged internationally. To be sure, at the frontline where towns and villages get pummeled by constant missiles and artillery fire, shelters are an essential tool of survival. However, more broadly in Ukraine, which has now experienced several years of intense warfare, many people rationalize risk and use shelters only in exceptional circumstances. This is relevant in relatively better protected cities like the capital Kyiv, but also extends to some contexts closer to the frontline.

A central question now – and in Ukraine’s near future as well – is how housing, public spaces and crucial infrastructures can be protected and fortified without causing major disruption to people’s everyday lives.

In Kostyantynivka, a small town close to the front in the region of Donetsk, reports indicate that at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion most of the town’s inhabitants headed to the available shelters with their children and pets. Since then this number has decreased drastically. This reduced use of bomb shelters persists despite the fact that the frontline continues to move closer to Kostyantynivka and the levels of danger are increasing. This process of change in the use of shelters, running contrary to international discussions around the protection of civilians, is familiar to many people in Ukraine. Not wanting to rely on general sentiment and the perspective from Kyiv entirely, we turned to relatives and friends from the region of Luhansk who had experienced the capture of the city in 2014, the invasion of Shchastya in the same year as well as the occupation of Lysychansk in 2022. In addition, people from other cities in Ukraine that are under frequent fire responded to our survey. Out of thirty respondents only four people stated that they would regularly seek protection in shelters when under fire.

The majority reflected the opinion that it is psychologically unsustainable to spend extended time spans in shelters when periods of danger and periods of respite become indistinguishable. In short, the perception of risk alters drastically if risk levels are constantly high. Accordingly, the planning and construction of protective infrastructure in the context of war needs to take into consideration – as with the planning of any other type of infrastructure – people’s patterns of engagement with those infrastructures in day-to-day life. Thus, a central question now – and likely in Ukraine’s near future as well – is how housing, public spaces and crucial infrastructures can be protected and fortified without causing major disruption to people’s everyday lives. Historical examples from places where people have had to come to terms with long-term scenarios of threat, for instance in South Korea, might provide productive, as well as cautionary, insights into such processes of planning. As many studies on infrastructure underline, referring to examples from around the world, – past and present – the reproduction of social inequality in infrastructural systems is a major issue. This is not only a concern in relation to infrastructures of war, whose inequalities are often blatantly visibly in the spatial distribution of death and destruction, but also in mundane, often less visible spaces.

Matters of inequality

The example of the city of Kryvyi Rih provides some important insights into deeply engrained and longstanding historical legacies of infrastructural inequalities. In Kryvyi Rih, iron ore has dominated life and materiality in the city since the nineteenth century. In the Soviet Union this exclusive focus on mining and steel production was driven to its extreme. By the 1980s Kryvyi Rih extracted almost half of the USSR’s iron ore. The city’s spatial organization, shape, landscape, housing and transport was largely centered around the mining industry. Yet, despite its importance for both the iron ore industry and the city’s residents, water infrastructure has received little attention thus far. Water supply in Kryvyi Rih has been primarily organized around sites of extraction, production and work. In planning, residents have featured as miners and steel workers. Accordingly, water reservoirs, lakes and supply lines have been organized around the need to cool iron ore plants and provide washing facilities for workers at the site of production. As a result, residential areas continue to be under- or poorly supplied. The quality of drinking water has been an issue for decades and the amount of clean water provided rarely meets the demand. Pipe pressure in housing complexes is low and even the very materiality of water pipes in Kryvyi Rih is a legacy of the city’s dependency on iron ore. Much piping consists of low-quality cast iron that has led to widespread rusting and degradation of Kryvyi Rih’s water infrastructure.

The privileging of industry over ordinary residents is a much older issue that is baked into originally Soviet infrastructural systems as well.

Kryvyi Rih’s transition to capitalism and the chronic lack of funding for public infrastructures have certainly exacerbated degradation and decay. Yet, it is important to note that the privileging of industry over ordinary residents is a much older issue that is baked into originally Soviet infrastructural systems as well. What is apparent in the present though is that private enterprises have emerged in the cracks of this crumbling Soviet infrastructure, offering clean water and enhanced pumping solutions to those who can afford them. This connects the contemporary city of Kryvyi Rih with sites of unequal water infrastructure on a global scale – from Michigan to Johannesburg. In their foundational volume in critical urban studies, “Splintering Urbanism”, Steve Graham and Simon Marvin survey comparable phenomena in cities around the globe, describing how ideas of the integrated, networked city have given way to the city of spatial and class fragmentation. As they make clear, the networked city has always been an ideal rather than reality. This is true for Kryvyi Rih, too. As the city’s splintering water pipes reveal, this particular type of fragmentation has been conditioned both by the legacies of mono-production and the emergence of free market solutions.

Usable presents?

Investigations into the usability of the past often reflect discontent with the present and the search for new utopias. The problems of contemporary Ukraine more generally, including but not limited to a focus on infrastructure, emerge from a different constellation. The selection, rejection and re-working of specific pasts is very much part of the country’s imagination of the future. At the same time, perhaps even more than in places outside the specter of war, the question of what to focus on in the present is a pressing one. In short, what is a useable present and how can it be improved? The northern suburbs of Kyiv present a case in point. Devastated by warfare, occupied and subjected to mass atrocities against civilians in spring 2022, areas around Hostomel airport, Bucha and Irpin have returned to some sort of normality of suburban life. Given the still visible damages, though slowly reconstructed and painted over, some of the central infrastructural concerns appear ordinary and mundane. How to alleviate the traffic jams between Irpin and the center of Kyiv along a vital road artery for work commutes? How to revive the economy around Hostomel airport which is the base for Antonov’s aviation industry that was destroyed in Russia’s early assault on Kyiv? At first sight, these are questions that seem removed from dominant debates on the war. Yet, a closer look reveals that these sorts of questions are vital to maintaining everyday life in a state of war and to envisage a life beyond it.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to the Kyiv School of Economics and, in particular, Tetiana Vodotyka, Academic Director of the Master’s program “Urban Studies and Postwar Reconstruction”, for facilitating this collaboration. We are immensely grateful to the countless people who maintain, repair and defend Ukraine’s infrastructure and society every day and under great peril.