The NGO personnel in Gaziantep’s office (Turkey) was in shock. Little groups were talking loudly in Arabic, or keeping their lips firmly closed. “It was an air-strike”, my Syrian office mate told me as he showed me two pictures just arrived from inside Syria. The car was a heap of smouldering scrap metal in the middle of a stone-paved road. “Of course, I know him”, he responded me as if the doctor were still alive. Dr Hassan Mohammed al-Araj passed away in Hama province, Syria, on 13th April 2016, the last cardiologist in this zone. Being a medical professional working in a rebel area makes you a target. The Russian air force supposedly targeted him via the SIM card left in his car to effectively geo-localise him, my informants suggested. A feeling of remorse engulfed my colleagues working from outside of the country to support those who risk their lives inside the country to delivery aid. However, after a time of condolences and the funeral, they kept working even harder, with no time for sadness. This was the only way to cope with the feeling of not working inside of the riskiest part of the map of fear.

How maps of risk and fear are being redrawn is the subject of Ruben Andersson’s ethnography of the global politics of fear and economies of risk and danger. The book is an prodigious collection of interrelated examples about the emergence of global danger zones from the Sahel to Afghanistan, explaining global and local complex practices of risk and fear, a psychogeographic journey around Western/-ers’ production of maps of the Other. Of course, this review essay is a reduction of the author’s 300 pages of research, good writing, engaging anthropology and farsightedness. As in his previous texts, which are very connected with the book, Ruben is one step ahead, showing new paths of analysis and inquiry on highly relevant topics. Thus, it is difficult to make a contribution to this thoughtful work. Nonetheless, I’ll try and offer a few insights, as the Allegra editors suggested, to enter into a dialogue with the book. I come to this discussion from my own research and experiences, based on my own ethnographic research (2019) about aid workers in Turkey managing the humanitarian operation for Syria, which has in some ways been inspired by the work of Andersson.

How maps of risk and fear are being redrawn is the subject of Ruben Andersson’s ethnography of the global politics of fear and economies of risk and danger. The book is an prodigious collection of interrelated examples about the emergence of global danger zones from the Sahel to Afghanistan, explaining global and local complex practices of risk and fear, a psychogeographic journey around Western/-ers’ production of maps of the Other. Of course, this review essay is a reduction of the author’s 300 pages of research, good writing, engaging anthropology and farsightedness. As in his previous texts, which are very connected with the book, Ruben is one step ahead, showing new paths of analysis and inquiry on highly relevant topics. Thus, it is difficult to make a contribution to this thoughtful work. Nonetheless, I’ll try and offer a few insights, as the Allegra editors suggested, to enter into a dialogue with the book. I come to this discussion from my own research and experiences, based on my own ethnographic research (2019) about aid workers in Turkey managing the humanitarian operation for Syria, which has in some ways been inspired by the work of Andersson.

As the initial vignette shows, the risks might be evident for some interveners, who know very well the ‘dragons’ inhabiting the ‘no go world’ — using Andersson’s words. At the same time, as Andersson aptly describes, I found other aid interveners who did not know anything about what was happening in the field, outside their bunkers and safeguarded offices.

This securitization produces frustration, but also indifference about the distant and remote.

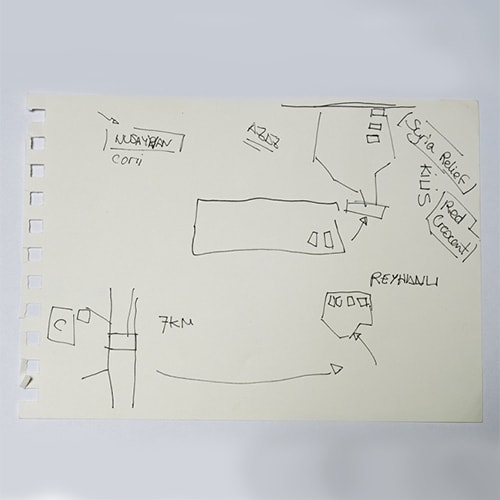

I have found some interveners who did not care about what was happening out there as result of the aid machinery solutions for interventions from afar. As example, a UN official in charge of some cross-border operations drew upon my request a map of how the humanitarian delivery takes place in the border (see featured image, above). As can be seen in the drawing of the Turkish side, Syria is out of out of the map, out of the page, only marked the town of Azaz in the other side.

Placing the no go areas outside the maps reminds me of medieval times, when the westernmost point of the Iberian Peninsula, the Cape of Finisterre – from the Latin finis terrae, which means the end of the earth — was land’s end, and left out the unknown.

In order to avoid risks and fears we simply cannot represent these on our mind maps, as expressed in the saying, ‘out of sight, out of mind’.

This mechanism holds true for the aid system because the division of labour and tasks, the power asymmetries between decision makers and implementers, and the fear to take responsibility for abundant failures, have produced a machinery where each person knows only one part of the aid process. At first glance, ‘being there’ is something for interveners to strive for – as it is for the anthropologists. However, accepting the mechanism of doing only my part allows knowing only one fragment of the map, the ‘safe go world’. The unknown, or the bulimic recurrence of dangers and risks in media, in politics, in donors’ interests, and in securitization training might create fear, as the book perfectly explains, but also ignorance and a lack of care about what is happening at a distance in the ‘no-map’. In other words, some interveners directly disregard the geography of fear or risk because it has no impact in their daily working lives. In the same vein, this no-care mechanism might work for people living in the go world. The other side of the coin might be those who risk their lives within the no-go-world, or just living among dragons — sometimes without any chance of exiting — as well as those interveners, like my Syrian colleagues working outside, whose greater knowledge is to know the risk map like the backs of their hands.

When I asked interveners to draw the humanitarian operation for me, some were blocked in front of the blank page, even when I added, ‘Imagine I know nothing about the operation’. That is the case of redrawing the maps with fears, they produce stories of dragons for many people who know nothing about the areas being redrawn. I agree with Ruben, in times of dystopia everywhere stories of utopias are needed, and if I might add something, stories of care about others to avoid the growth of dragons.

References

Fradejas-García, Ignacio (2019) Humanitarian remoteness: aid work practices from ‘little Aleppo’. Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 27(2): 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12651

Ruben Andersson. 2019. No Go World How Fear Is Redrawing Our Maps and Infecting Our Politics. University of California Press.

Featured image © Ignacio Fradejas-García.