Through the notion of simultaneity I explore the emotional and affective dimension of the displacement-emplacement continuum within transnational migration and hint to the need to consider perceptions of time and space in people’s lived experience.

Accompanied by the familiar ebbing and flowing chatter of a dozen women talking in three languages, I sit down next to Yasemeen[i]. Her heavy body rests in one of the second-hand armchairs that furnishes the assembly hall. The numerous plates still half filled with home-made delicacies draw a colorful pattern on the table in front of us. They evoke both the care invested in their preparation and the craving which violently erupted once the long anticipated end of Ramadan had finally arrived. It is June 2018 and we[ii], members of an international women’s initiative, celebrate Eid al fitr in the central German town of Göttingen. Yasemeen has withdrawn her head-scarf. Her shoulder-long hair shimmers in brown and violet tones, matching the firm brown skin of the fifty-five-year-old. She has finished eating and strikes her round belly with a fleshy hand – a belly that had carried seven children. Yasemeen is very sick, she has cancer. The year before, she had been hospitalized for two months. Recently, she told me that she needed a gall surgery. Yet another surgery.

“How are you? What happened to your surgery?” I ask in Persian. Yasemeen was born in Herat, in Afghanistan, and had spent more than half of her life on the other side of the border, in Mashhad, Iran. From there, she immigrated to Turkey, and then to Germany where she has lived for two years with her husband and two youngest children. In her characteristic mix of Iranian and Herati dialects she answers “Look how swollen my belly is again. It hurts. I saw my doctor today. Galle (gall) they say, right?” I am surprised “How come you know this word in German?” “You know, I try to learn all the medical expressions.” She laughs. She is very grateful for the social and medical care offered by the German state, she had told me before. Her aim is to learn German well enough to be able to talk to physicians without need for translation. To get there, she is willing to make efforts: “It’s not like I was very educated, I am poorly educated, and I raised seven children, my brain is broken”. This discourse parallels the German immigration policy’s principle which is to encourage, but also to expect integration. Thus, to Yasemeen, besides taking initiatives in the women’s group, acquiring language skills is a way by which she tries to reach emplacement, what Bjarnesen and Vigh (2016, 10) define as the striving to be “positively located in a relational landscape”.

For the moment, Yasemeen goes on to explain, she has postponed the surgery. My careful listening encourages her to share more bad news “Yesterday I cried all night. Sonjajân, my son in Iran is now in hospital.” She had told me before that her 27-year-old son had been deported back to Afghanistan from Germany, while she and the others had received asylum. He lives alone in her former home town. His illness is probably a source of shame, because Yasemeen never made clear which disease he was affected by. She tells me that her other son, who also lives in Mashhad, would not be able to take care of his brother because “he barely makes ends meet for his own young family. There are no jobs, especially not for Afghans” (interview May 2018).

Her son’s deportation does not only bring underlying discord within the transnational family to the surface. His experience of displacement, i.e. a disruption in which “the formerly familiar seem foreign and frightening” (Bjarnesen, Vigh 2016: 10), also resonates with her own memories of feeling disconnected, alienated and excluded in Iran. “If only I had a passport I would go to Iran and look after this ill-fated (bisarnevesht) child” (interview May 2018). Yasemeen’s discourse reflects feelings of helplessness, shame and guilt which are connected to transnational family relations and deportation (Baldassar 2015; Drotbohm 2015). Further, her serious medical condition, exasperates the incongruity with her son’s state of dislocation. In sum,

Yasemeen begins to experience emplacement in Göttingen at the same time as she feels displaced both in the present relation with her son, and in her past relation with Iranian society.

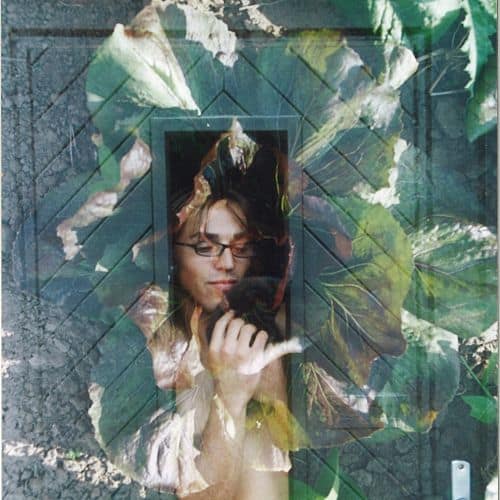

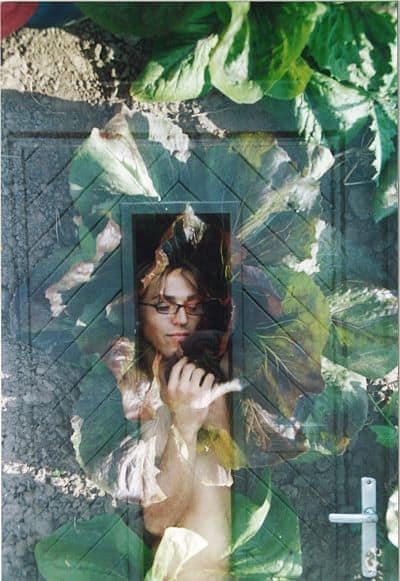

To illustrate Yasemeen’s emotional world on this summer evening, let us remember the times of analog photography. In double exposure, two different motives are captured in one frame, whether accidentally or intentionally. Each picture simultaneously represents and evokes different emotional and affective experiences (see Edwards 2012). In Yasemeen’s example, the superposed affective motives refer to different places and to different moments in time. Within the resulting photograph, we see an unintended simultaneity emerge.

A reflection about the notion of simultaneity allows us to consider the emotional and affective dimension of the displacement-emplacement continuum in the context of transnational migration. Emotion and affect are relational in nature[iii]. They are the origin and the result of our interactions with the social world and as such relevant to the study of displacement and new sociabilities.

The idea of simultaneity is central to research which examines discourses and practices that take place within so called “transnational social fields”. Nina Glick Schiller and Peggy Levitt (2004, 1003) conceptualize simultaneity as the practice of “living lives that incorporate daily activities, routines, and institutions located both in a destination country and transnationally”. The notion is used to explain migrants’ strategies for creating capital at different places “at the same time” (see for instance Nieswand 2013; Nowicka 2013). Yet, the concept remains not sufficiently conceptualized. Is the simultaneity that is claimed in anthropological analysis the same as that perceived by research participants?

Ancient philosophy noticed the importance of sensory perception to the understanding of simultaneity. In modern physics, it is widely acknowledged that the simultaneity of two spatially separated events is not absolute, but relative to the observer’s reference frame. Following Einstein’s theory of relativity, the time of an event needs to be defined as the time in which the observer sees the event (Jammer 2006, 109). A focus away from strategies and practices and instead, towards emotional and affective dimensions (Svašek 2010) offers unexpected insights into the role of time and place within migrants’ lived experiences.

The relative importance of time and place in transnational lives has been subject of recent research that investigates the simultaneous articulation between displacement and emplacement. These studies highlight, on the one hand, the important role of particular places, even for people in transit (see for instance Lems 2016; Drotbohm and Winters 2018). Indeed,

Yasemeen’s emotional and affective responses indicate her awareness of the distinct “feel” of both Göttingen and Mashhad that emerges from their respective legal, political and social conditions. On the other hand, these studies indicate the relativity of place as displacement and emplacement both may and may not involve physical mobility (Vigh and Bjarnesen 2016).

A double exposure may capture two motives referring to different places in one photograph. Through Yasemeen’s emotions and affect, it feels to her as if she is simultaneously in Göttingen and Mashhad. Yet, her awareness about the structural impossibility of traveling lets her know that she is not.

A double exposure may also capture two motives referring to different times. Displacement and emplacement represent ever incomplete processes (Malkki 1995).

Within a present experience of displacement, people may live in a continuous state of becoming in hope of future emplacement or in the nostalgia of past feelings of embeddedness.

The following example elucidates further the temporalities connected to the experience of affective simultaneity.

Hamid, a resolute, short 69-years-old, has been living in Babol for six years, the town in the north of Iran where he grew up. I have known him when he still lived in a small German town at the coast of the North Sea. After spending more than half of his life in Germany, his return migration is connected to professional failure, sickness and divorce. Nevertheless, the walls of his living room decorate the same printed paintings as had his former home.

Although I could see, during my visit in Babol, that he feels belonging to this city, he never stopped complaining about the aggression he observes in his daily interactions: “Nobody respects the rules here!” (fieldnotes, November 2017).

Recently, when workers he had hired, were putting new tiles on the external walls that delimit his property, a municipal officer rang at the door. Someone had filed a complaint. Hamid was summoned to the townhall. “So I went, but the way you are served there is very condescending. They act as if they are doing you a favor although they are supposed to solve people’s problems.” After being sent from one desk to another to fetch signatures, Hamid also had to show his property to an engineer. “They made me wait two more days, then suddenly I lost my temper. I said: ‘Shame on you! I am an elderly person. You send me from one office to another. I collected twenty signatures. What for? …Tell me, what do you want from me? Money? I’ll give it to you. I lived in Germany for 35 years. Never did such a thing occur to me there! You should deal with people in a factual way. If someone made a mistake he has to pay, but you should not be acting up with somebody’” (interview July 2018). The simultaneity that arises from this account is one that cuts through time: His anger expresses his estrangement with procedures in Iran. His reaction contains feelings of integration and appreciation in relation to his past life in Germany (while memories of exclusion are silenced) and momentarily become part of his present.

Affective simultaneity may challenge taken for granted understandings of space and time in anthropological research. Accounting for people’s lived emotional experiences is crucial in the study of socialities emerging within an increasingly interconnected world.

Hamid’s reactivation of past emplacement in Germany allowed him to turn his displacement in Iran into emplacement: “What happened then?” I asked. “Nothing, they looked down and hurried to end the procedure… They are not used for people to get angry… people here are afraid of contesting anything.”

Bibliography

Baldassar, Loretta. 2015. “Guilty Feelings and the Guilt Trip: Emotions and Motivation in Migration and Transnational Caregiving.” Emotion, Space and Society 16 (August): 81–89.

Drotbohm, Heike. 2015. “The Reversal of Migratory Family Lives: A Cape Verdean Perspective on Gender and Sociality Pre- and Post-Deportation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (4): 653–70.

Drotbohm, Heike, and Nanneke Winters. 2018. “Transnational Lives en route: African Trajectories of Displacement and Emplacement across Central America.” Working Papers of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz 175.

Edwards, Elizabeth. 2012. “Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (1): 221–34.

Jammer, Max. 2006. Concepts of Simultaneity: From Antiquity to Einstein and Beyond. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lems, Annika. 2016. “Placing Displacement: Place-Making in a World of Movement.” Ethnos 81 (2): 315–37.

Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1002–39.

Malkki, Liisa H. 1995. “Refugees and Exile: From ‘Refugee Studies’ to the National Order of Things.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 495–523.

Massumi, Brian. 2015. Politics of Affect. Polity, Cambridge, Malden.

Nieswand, Boris. 2013. “The Burgers’ Paradox: Migration and the Transnationalization of Social Inequality in Southern Ghana.” Ethnography 15 (4): 403–25.

Nowicka, Magdalena. 2013. “Positioning Strategies of Polish Entrepreneurs in Germany: Transnationalizing Bourdieu’s Notion of Capital.” International Sociology 28 (1): 29–47.

Svašek, Maruška. 2010. “On the Move: Emotions and Human Mobility.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (6): 865–80.

Vigh, Henrik, and Jesper Bjarnesen. 2016. “The Dialectics of Displacement and Emplacement.” Conflict and Society 2 (1): 9–15.

[i] All names are pseudonyms.

[ii] This “we” refers to the fact that I have participated in this group as an activist and researcher for ten months in 2017 and 2018.

[iii] In a Spinozian sense, affect refers to the “capacity of affecting and being affected” (Massumi 2015, 3f.) in a primary rather physical and sensorial way, while emotions represent the subjective expression of the experience.