The first ever team comprised of refugees debuted at this year’s Rio Olympics. They were the penultimate team to enter the Olympic stadium, coming in before Brazil, and received resounding applause as Rose Nathike Lokonyen, the twenty-one-year-old track runner from South Sudan, led the way wielding the Olympic flag.

While none of them medalled, they impressed. They did not make the podium, but they made a statement. The message these athletes hoped to send was that refugees are still capable of doing something.

Their faces were all over the internet, their stories of escape and their life histories in camps told over and over through advertisements and celebrity endorsements. It was a beautiful two-week moment to witness. Suddenly it was ‘cool’ to support refugees after years of a so-called crisis has fallen on the deaf and jaded ears of the international community. These ten refugees transformed from being perceived as sub-humans to super-humans, from victims to heroes.

I had originally expressed concern at the start of the Olympics that the categorization of refugee athletes into a separate team would reassert preconceived notions of refugees, shore up Europe’s guilt, and reiterate a false sense of inclusion.

I hoped that the act of ten refugees entering the stadium carrying the Olympic flag would “instead be a bold declaration of authentic unity, transcendent of nation-states, refuting the exclusion of those whose statelessness means they do not belong.”

A celebration of difference, strength, and sportsmanship that the Olympics have asserted even through modern history’s darkest periods.

This celebration did take place. But it may have felt a bit clumsy. In Rio’s stadium stood ten figures who have challenged the obstacles that challenged them. Cheering them on—by far the loudest standing ovation of the night—was the international community, the very same community who has thus far expressed its support for those left out of the nationalist picture with deafening silence.

As one Facebook commenter so astutely stated, “I think that we should be proud of ensuring that the world is peaceful [instead of] celebrating the life of people who live [in] exodus due to conflict we can solve together.”

Others attempted to respond to the disguised isolation of refugees from the international community by supporting the almost oxymoronic concept of the Refugee Nation. Essentially this ‘nation’ attempts, which Sophia Hoffman believes is the point of refugee camps, the “reinsertion of sovereign-less people into the system of sovereignty”.[i] So what does the Refugee Nation look like? One giant refugee camp of diverse populations under one flag? A microcosm of the international community?

The Refugee Nation is a tricky concept. If we look at it through Benedict Anderson’s “imagined communities” we might understand that displaced people share a sense of overall unity because of a common denominator of statelessness—just as a New Yorker might feel a similar connection to someone from Los Angeles if they were to meet outside of the United States because she imagines that they share cultural history and traditions. However, we must also understand that the Refugee Nation is comprised of inter-national individuals. Despite statelessness, most refugees continue to identify with their nations of origin: Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and the DRC to name a few.

The Refugee Nation attempts to transcend these differences while also celebrating them—perhaps what the nation-state strives to do but so often fails—aiming to rise above the divisiveness of nationalism while also fitting into the nationalist fabric.

It is essentially a nation of misfits; in Rio, the refugee team included those whose countries have a complicated relationship with the IOC, like Kuwait and Russia.

Displaced people in our time are so-called because they are mis-placed, “they did not fit the nationalist project of ‘one state, one culture’,” as Ernest Gellner wrote in 1983. Nationalism inherently reinforces the idea of Othering, “since by its nature the idea of a nation to which a particular people belong excludes those who do not,” as John McHugo asserts. [ii] Indeed, every two years the Olympics is a demonstration of nationalism’s “two-faced” quality, which Yahya Sadowski argues “can trigger both altruistic love of country and genocidal xenophobia”. [iii]

What does it say about the repercussions of nationalism when an invented state belonging to those rejected from their own is symbolized by a flag designed to look like a life jacket, an homage to the thousands who have lost their lives crossing the sea between two nations who don’t want them?

Still, we nevertheless witness the strengthening of nationalism by the very existence of those who do not fit into it. From a different angle, if the presence of millions of displaced people threatens nationalism, Palestinians and Kurds would not be fighting for recognized statehood. And the Refugee Nation, the brainchild of a project of the same name that fights for just this, advocated for its flag, designed by Syrian artist Yara Said, to be recognized by the IOC. While the refugee athletes ultimately carried only the Olympic flag, their nation now has an anthem, composed by Syrian musician Moutaz Arian, created to be played during medal ceremonies.

But the Refugee Nation project, though well intended, falls short of its goals. Its thinking, displayed on the home page of the project’s website, echoes the simplistic definition put forth by IOC President Thomas Bach, who said, “These refugees have no home, no team, no flag, no national anthem”.

Both seem to forget, or at least they fail to acknowledge, that refugees’ devotion to the countries from which they were forced to flee does not merely reflect a wish to one day return, whether in the future or in the past, but a genuine sense of national identity.

The Refugee Nation project is simply a response to the shortcomings and dangers of exclusivist nationalist spirit in the only way our generation knows how to respond: by creating for the misplaced their own nation. In this way, perhaps a Refugee Nation attempts to set a positive example of the ideal nation—a practical solution to the failure of international unity—but if it hopes to re-assert the rights of refugees as members of a universal community, it should do so in an innovative spirit that nods to something greater than nationalism rather than merely imitating it.

For example, why do refugees need a refugee flag? The flags they once waved as citizens of their country do not lose meaning once these citizens cross the border. Many refugees continue to wave these flags in pursuit of home while surrounded by the flags of the host country. If the intent is to re-make a place for those who do not have one, letting refugees wave the flags of Syria, South Sudan, and Ethiopia separates them from the international community far less than a flag that embodies their isolation.

For example, why do refugees need a refugee flag? The flags they once waved as citizens of their country do not lose meaning once these citizens cross the border. Many refugees continue to wave these flags in pursuit of home while surrounded by the flags of the host country. If the intent is to re-make a place for those who do not have one, letting refugees wave the flags of Syria, South Sudan, and Ethiopia separates them from the international community far less than a flag that embodies their isolation.

So while the refugee athletes did not make the podium in this Olympics, the creation of the Refugee Team and the attempted Refugee Nation has placed them on a platform. They continue to be categorized as not belonging and statelessness is repeatedly imposed upon them. But, as the athletes have shown us, there is optimism still. At least for two weeks they have had international attention. At least the creation of Team Refugees allowed the international audience to support their own nation as well as athletes from all over the world, possibly bringing us as close to an internationalist spirit that the Olympics has ever done while still being concerned with the national medal count.

History has shown that nationalism only grows stronger and nationalist projects only more exclusive, so at this historical moment it seems that our best hope for the refugee athletes, as many of them have so far expressed, is that the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo witness them competing on behalf of their nations of origin or host nations as they wish.

We should look forward to learning more about them individually through in-depth coverage that goes beyond their stories of flight to focus on their achievements, talents, and personalities. We should ask what they hope to see in a Refugee Nation and what they hope to represent as “citizens” of the team. We should respect them as flag bearers of the Refugee Nation as a symbol of their resilience but also of their nations as a reminder of their histories—as well as of the Olympics as an emblem of the potential universalism that we can choose as an outcome of crisis and conflict.

For the rest of the refugee population, we should love them as much as we love their fellow Olympians.

[i] Sophia Hoffman, “A Sovereign for All: The Management of Refugees as Nation-State Politics,” in The Politics of Humanitarianism: Power, Ideology and Aid, ed. Antonio De Lauri (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016), 162.

[ii] John McHugo, Syria: From the Great War to the Civil War (Saqi Books, 2014), 46.

[iii] Yahya Sadowski, “Evolution of Political Identity in Syria,” in Identity and Foreign Policy in the Middle East, ed. Shibley Telhami and Michael Barnett (Ithaca, 2002), 152.

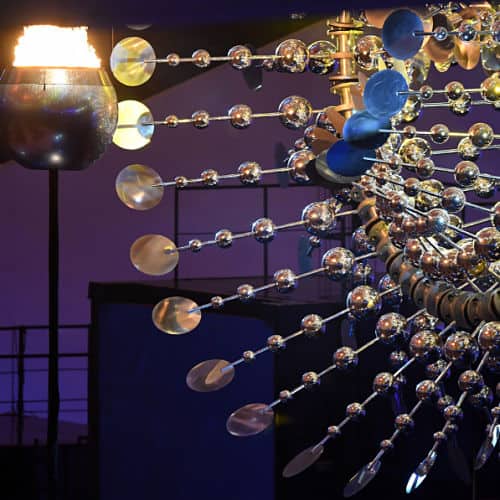

Featured image by familymwr (flickr, CC BY 2.0)