“Why do most of the paintings speak of war?” Dima, barely nine-year-old, asked me.

This summer, as my Royal Jordanian flight descended over a pale Baghdad enveloped in a yellowish and polluted hue, I knew I was not landing in the city of my childhood – that capital of the Abbasid dynasty whose sophistication endured for centuries until its fall in 2003 – but its mirage.

At the airport, a once-elegant edifice whose ceiling alluded to the now-disappearing palm trees, I received no “welcome home” at passport control.

Instead, a young mustachioed chap that could easily be confused for one of Saddam Hussein’s Ba`ath Party apparatchiki reprimanded me for not renewing my passport, then motioned me in.

I lived 29-years in Iraq before leaving in 2021. Still, during my brief stint away the city’s urban fabric was altered beyond recognition. The elegant middle-class villas are gone, making way for ghastly high-rises coexisting with war’s paraphernalia like checkpoints, militia flags and dead concrete barriers.

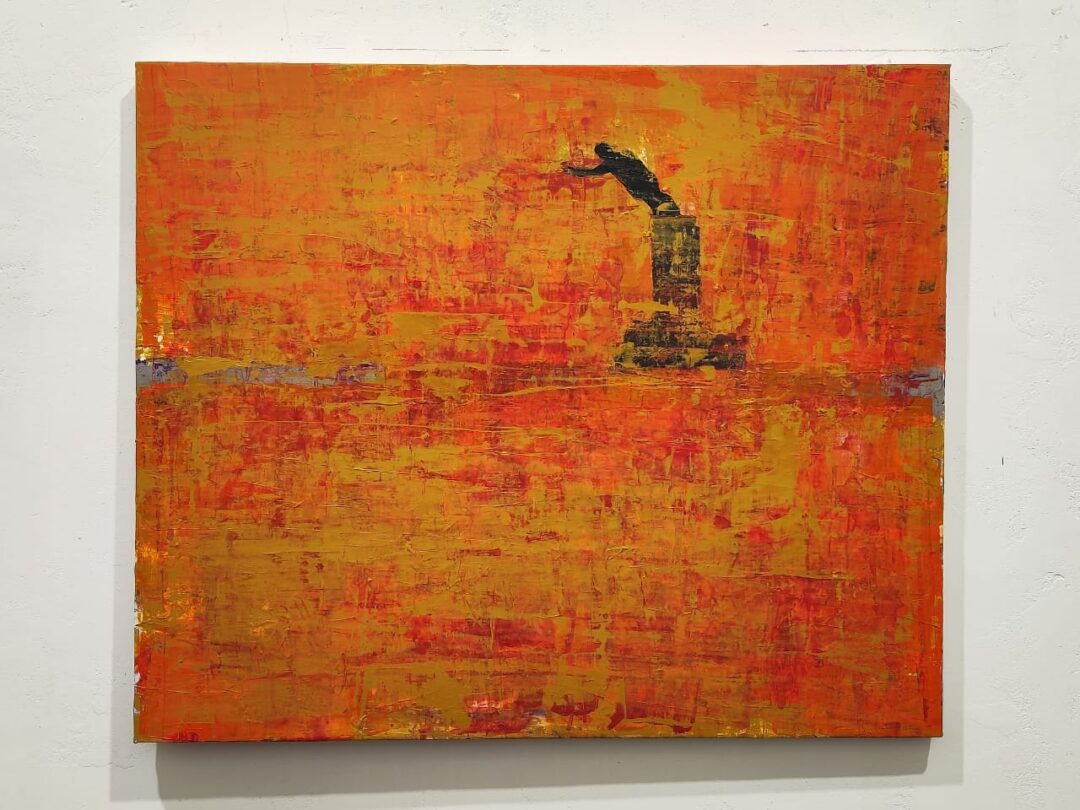

The landscape was haunted, war lived in screaming craters and bullet holes, incarnated in the mangled iron lining roads and assailing the denizens passing through. Artist Mohammed Abdul-Wasi (b. 1986) painted this traumascape for his solo-exhibition, Coup. I decided to go see his show.

Coffins, decapitated statues, white tents for the displaced, and a portrait of a martyr perished in the war against the Islamic State that killed and forced millions to flee, ghostly elements inseparable from a dark choreography saturated with violence and forcibly familiarized by modern warfare.

This is a portrait for a present where the past, the future and the environment fall victims of what language fails to name.

One surrealist scene shows a Sumerian head cut and flung on scorched earth. Its eyes hollow, its mouth gaping. The ziggurat of Ur loomed faraway under a reddening sky. This is a portrait for a present where the past, the future and the environment fall victims of what language fails to name.

Sargon Boulus, an Iraqi poet born not far from where I saw the first light to the west of Baghdad, was haunted by the specters of his family and friends, of the children and bereaved mothers of Iraq. On a visit to The British Museum in London, he stood by an Assyrian artifact, thinking.

“What have you seen, wide Sumerian eyes?” he would later write. “Which thief, cursed be his hands, brought you to this island? / Who shall kneel before you in this vault?” In this alien geography of impassable necropolitan borders, not even the eyes of Sumerian ghosts were destined to meet.

Museums straddling the Atlantic have long housed Gods kidnapped from African and Asian lands. Colonial officers sever the umbilical cord tying them to peoples they kill, ransack and conquer, leaving them as neutralized, ritually-orphaned aesthetic objects for passive tourist contemplation.

Many of these came from the ruins of Mesopotamia, in today’s Iraq.

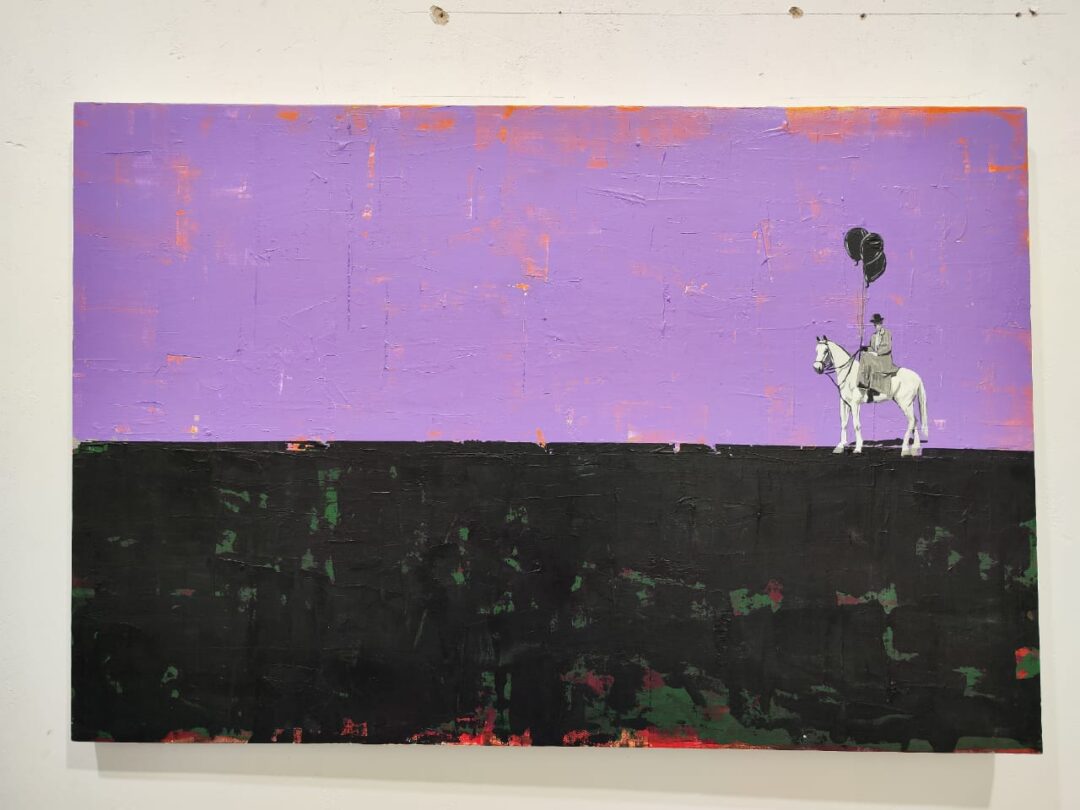

In the 1920s, Gertrude Bell, British spy and adventurer, served as the Director of Antiquities in King Faisal’s Iraq, a position allowing her to oversee excavations and decide on the artifacts that stayed, and those European archaeologists would take home. At times, she did so by the toss of a coin.

Bell helped found the National Museum of Iraq, which she would call “my” museum. But under the Antiquities Law of 1924, writes Shimrit Lee in Decolonize Museums, Bell allowed a significant number of material, including a Bull Headed Lyre that went to Penn, to leave the country.

In one of Wasi’s paintings, Miss Bell, riding a white horse like a false prophet, enters the frame into a desolate landscape to inscribe her colonial insignia. The sky is purple, quite exotic for her own eyes. In her hands are the strings for three balloons, black, like the promise of European progress.

Iraq’s Lamassu winged-bulls no longer stand guard by the gates of Assyria. The kings’ palace near Mosul was blown up by ISIS. Some of these celestial beings are now held captive in Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Yet nothing compares to the loss that was still to come.

“Several archaeological dig sites, some spanning the length of 40 or 50 football fields, suffered greatly from air attacks in addition to the looting during the 1991 war,” Amy E. Miller writes of the Gulf War aerial campaign, which infamously sent Iraq back to “the pre-industrial age.”

The post-Gulf War smuggling was encouraged by the hardships introduced by the embargo imposed to punish Iraq over its occupation of Kuwait.

During my visit, I saw how ordinary folks still repressed the memory of the unsayable.

On the eve of Iraq’s invasion by a global force spearheaded by the US in 2003, scholars pleaded with the George W. Bush administration to spare Iraq’s heritage the imminent destruction. Thousands of artifacts were looted from major museums instead. Invading troops stood idly by, watching.

Art historian Nada Shabout would later recall how, in war’s aftermath, if we can call it as such, Iraqi “artists felt embarrassed about the looting and destruction and shied away from talking about it.” During my visit, I saw how ordinary folks still repressed the memory of the unsayable.

Two decades after they were “shocked and awed”, the fires in the claustrophobic fields of yesteryear still burned. It is understandable, then, that Wasi’s nightmare-scapes in his first, crude attempt were littered with detritus. Death of matter and (wo)man remains an inescapable literary and artistic motif.

But if the looting was a source of embarrassment to Iraqi artists, what do we call the state of culture temples in the country today?

At the derelict Ministry of Culture is Faiq Hasan’s Gallery. Named after the pioneer who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and whom Jabra Ibrahim Jabra called “the doyen of Iraqi painters”, it is where the works of masters like Shakir Hasan Al Said and Jewad Selim were finally on display.

Thankfully-but-sadly, on two visits, the gallery was empty. Two employees, one a self-described artist, seemed unsure which artworks belonged to whom. Many lacked description cards. Unnamed, these invaluable pieces stood like fugitives in continuous exile.

As fires erupted in the building, Iraq’s visual culture was being blinded.

Shortly after the fall of Baghdad on the ominous day of April 9, thousands of artworks were looted from the Museum of Modern Art. As fires erupted in the building, Iraq’s visual culture was being blinded. A subsequent basement flood then damaged whatever escaped the original rampage.

Iraq has since degenerated into an age of state-led mediocrity (at the Ministry, there were no clean restrooms, and one couldn’t find a water fountain at the National Museum, which somehow closes its doors around noon, either). Now, at least, these recovered artworks are on display.

An aging door to a separate upstairs gallery opened to a loud crack that reminded me of gunfire. In a dimly-lit corner, by the paintings of Jewad’s siblings, Nizar and Neziha, the window pane remained cross-taped, a relic from the long years of war disgorging on the asphalt of Haifa Street outside.

Nizar Selim’s painting paid homage to poet Nizar Qabbani and his Iraqi wife, Balqis al-Rawi, killed in the 1981 bombing of the Iraqi embassy in Beirut. Lines from Qabbani’s elegiac poem, Balqis, course through the piece: “What Arab ummah savors the assassination of a nightingale’s voice?”

At the time, Beirut was in the throes of a devastating civil war (1975-1990) that left over a hundred-thousand fatalities. The Israelis would later besiege and pummel the city, and factions like the Lebanese Phalanges Party committed heinous massacres in places like Sabra and Shatila (1982).

Now Beirut is again in the news and under Israeli bombing, waiting, or turning her face to the sea.

Downstairs at the ministry, my niece moved in awe between the faces horrified amidst the carnage in Hasan’s disturbing canvas, the fires engulfing an abode in Layla al-Attar’s piece, and the hanged Communists in Tareq Madhloum’s spellbinding commemoration of the Wathba Uprising of 1948.

“Why do most of the paintings speak of war?” Dima, barely nine-year-old, asked me.

I remembered her voice reading of the inauguration of new galleries at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, dedicated to the wars on Afghanistan and Iraq. According to a Marine Corps Times reporter, “the Iraq gallery in particular seeks to put visitors on the ground there.” He goes on:

“With a warning before visitors enter an Iraqi village, a “scent cannon” greets them, reminding Marines of the smells of burning garbage, plastic and cordite that characterized the scent of deployment for many of them.” The only scent I remember was that of narenj flowers in bloom.

[…] an image the grotesque would banish and replace,

Neo-colonial Orientalism aside, the dalliance with nostalgia, and the logic of capital underneath, are difficult to miss. Empires have long invested in future generations to fight future enemies in future battlefields with future supplies from the weapons manufacturers of today.

The countryside of Iraq, celebrated in the poetry of giants like Saadi Youssef and Muzaffar al-Nawwab, was one of leftist, anti-Ba`ath activism, and slender boats gliding on the face of rivers whose bends palm groves graciously embraced – an image the grotesque would banish and replace.

Think of the town of Haditha, with its water-wheels on the Euphrates. So peaceful, until one November morning in 2005, Marines killed twenty-four men, women and children in an unpunished orgy.

A recent investigation by The New Yorker had some images to show. One belonged to a three-year-old girl. Her name was Ayesha Younis Salim. She was shot to death, then one “Marine wrote the number twelve on her cheek” to mark the victims as they were being photographed.

A crime no monument so grandiose to keep in its shadow.

Sources and further readings

Guirguis, Laure: Arab Lefts : Histories and Legacies, 1950s 1970s. [Place of publication not identified]: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Lee, Shimrit: Decolonize Museums. Edited by Bhakti Shringarpure. New York: OR Books, 2022.

Miller, Amy E.: Looting of Iraqi Art: Occupiers and Collectors Turn away Leisurely from the Disaster, 37 Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 49, 2005.

Nusair, Isis: “The Cultural Costs of the 2003 US-Led Invasion of Iraq: A Conversation with Art Historian Nada Shabout.” Feminist Studies 39, no. 1, 2013, pp. 119–48.

Sassoon, Joseph: Saddam Hussein’s Ba’th Party : Inside an Authoritarian Regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Photo credit: Local artist Wijdan al-Majid’s murals pay homage to pioneers Jewad Selim and Hafidh al-Droubi. Baghdad, July 2024. Courtesy Nabil Salih.