The Institute for Critical Social Inquiry (ICSI) is a program run by The New School for Social Research for the second time this year. It brings together graduate students and junior faculty members to attend intensive seminars ran by distinguished thinkers at The New School’s campus in Greenwich Village, in New York City. This year, participants will have the privilege to work in close collaboration with Jay Bernstein, Gayatri Spivak and Judith Butler during an entire week. Applications are now open and financial support is available. Have a look here for more info.

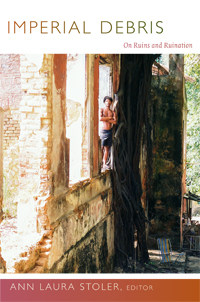

Allegra sat down for a virtual interview with the program’s director, Ann Stoler, a renowned post-colonial historian and anthropologist whose most recent work includes Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (2013) and Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (2009) and we look forward to her new book Duress: Concept-Work for Our Times coming out with Duke University Press next year. Here is what we discussed…

Allegra sat down for a virtual interview with the program’s director, Ann Stoler, a renowned post-colonial historian and anthropologist whose most recent work includes Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (2013) and Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (2009) and we look forward to her new book Duress: Concept-Work for Our Times coming out with Duke University Press next year. Here is what we discussed…

Julie: We, at Allegra, have always looked up to The New school as a refuge for radical critical thinking, a bit like the « University of Muri », the imaginary university of Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem. It is a similar refuge, away from the increasing neoliberal pressure imposed on our universities, that we – at our very small level – are trying to preserve via the online world. In which ways does the ICSI embody the ‘spirit’ of The New School?

Stoler: Thank you for your thoughtful questions and provocations. ICSI to my mind is so much in the spirit of The New School I’m not sure I can count all the ways. My first priority is to make sure that a range of young scholars in the making, seasoned ones, and otherwise strapped and harried intellectuals around the world can have the opportunity to take out time to think otherwise (Foucault’s wonderful injunction to himself and us to “penser autrement”) in a setting that encourages them to do so. Not everyone has the time or funds to take off for a full summer course which is precisely why I did not go for one. I chose a time frame and moment in the academic calendar when classes are over in many places. We designed a tuition scale that would allow advanced doctoral students, post-docs and faculty who do not have access to university funds, to make this work for them. We supply dorm rooms at the new University Building on 5th avenue at a reduced rate.

But most importantly, this institute is designed for academics seeking an infusion of learning—those of us who never had the opportunity to learn about a certain philosopher or a certain way of thinking about which we’ve yearned to know more. How many of us have the time to read Heidegger? Or Hegel? How many of us have the time to study Marx’s work and how it speaks to contemporary social, economic and political issues?

I’ve chosen a range of leading scholars who are brilliant, generous, and politically engaged—people who are not content to do “critical theory” exclusively, but those who care about the resonance that conceptual work has in the world. They are scholars who are eager to explore how critical social inquiry can be used to confront diverse predicaments and situations.

The ICSI pays homage to the University in Exile by rethinking how truth, parrhesia, and “fearless speech” can address our worldly conditions. It’s designed to facilitate an environment that challenges the analytic and conceptual vocabularies and frames that have been central to intellectual work.

Julie: You chose well established scholars to run your seminars and it seems like you want to bring their thoughts as closely as possible to participants during this one week of intensive training. The kind of relationship that the ICSI seeks to establish between senior and junior scholars resembles the one of the Master and its apprentice. Why did you choose such a “somewhat old fashioned” model? Why not a ‘summer school’ instead?

Stoler: By “masters,” I don’t think about those who sit in an ivory tower, but those who engage with and are shaped by their pupils. I don’t think about those who are geared so much to answers and resolution but to a way of thinking, a style of thought, that places, as one of its first questions, “Are certain queries worth answering having answers to?” And, “How are those assessments made and by whom and for whom in the world today?”

In his beautiful book, Lessons of the Masters, George Steiner understands teaching in two ways: positively, i.e., “share this skill with me, follow me into this art and practice, read this text” and negatively, i.e. “do not believe this, do not expend effort and time on that.” The teacher and student, as Marx said, should “Exchange trust for trust … the teacher solicits attention, agreement, and optimally, collaborative dissent.” Informed dissent is what we are after. We are also informed by the teachings of Socrates, who encouraged people to be in the presence of wisdom that manifests as a “clear perception of his (sic) own unknowing.” We are also inspired by the Zen masters and hail great teaching as that which instills insomnia, the exhilaration that dispels somnambulists and defers sleep. None of us slept very well during the ICSI week this year!

The master class is an occasion to think hard about critique as an “ethics of discomfort.” And maybe we’ll find that the ICSI master classes are transformative, not only revealing the lessons of masters, but what a master is and should do and be.

Julie: I see…the ‘Master Class’ as a ‘caquetoir’, to use De Certeau’s definition of the seminar: a place or a moment when a certain “politics of word” is expressed through real (!) participation and public intention…

Stoler: I love this! What a wonderfully rich way to think about this venture: De Certeau’s notion of the seminar as a place that can produce a common language and a personal way of speaking, a meeting place, a “plural laboratory.”

Julie: What kind of intellectuals do you aim to produce through the ICSI? Why do you think this intensity is productive or adequate to shaping contemporary thinkers? On the contrary, we, at Allegra, tend to think that ‘slow food for thought’ is better than intensive productivity.

Stoler: I totally agree with the notion of “slow food for thought,” but there are many different ways to prepare for such an exercise, and to cultivate a capacity to do so. Foucault’s warning that genealogy is always slow and belaboured is one I take to heart. As one who has worked on tedious colonial archival documents for so many years, as one who has amassed an archive for some twenty years on the French Front National, as one for whom new books take a decade or more to think and write, the notion of sharing ways of learning to attune oneself to the details of thought and practice is something I cherish. But this doesn’t just come from saying “I’m going to work slowly.” One has to be trained to sense and see discernments and details. One has to learn how to question one’s own most cherished thoughts, particularly those that seem most clear and most obvious. Getting there is no easy task. Most of my own teaching is about how to pause, to work between the empirical and analytic details, to learn how to ask better questions and about the phronetic work allows one to do so. How do we learn to identify what Roland Barthes called “the punctum”—that which pricks and shocks?

Julie: Last June was the first year you ran this “experiment” (is it the correct word?). You invited Talal Asad, Simon Critchley and Patricia Williams to ‘inaugurate’ the program. Why these three scholars? And what did you learn from this first experience? What kind of feedbacks did you receive? Did the program get slightly ‘tweaked’ after its first session?

Stoler: It is an experiment (thank you) and I hope it remains one. The size of the Master classes is key; they’re never more than 20 odd fellows, sometimes less. Readings are provided a month in advance so that new conversations can take place right away. The inaugural year of ICSI was astounding, a vibrant experience. Each of the seminars provoked more questions than they could address. Each one produced new exchanges and conversations with fellows from Pakistan, Australia, Denmark, India, Brazil, Goa, the U.S. and elsewhere. We had fellows from seventeen countries who brought their unique energy and knowledge.

They did more than make it work; they transformed the ICSI in its very formation and shaped its course. For example, they decided to interview the seminar leaders; scholars met with the Masters outside regular seminar hours, and through the week, transformed our aspirations. This might sound over the top, but there were fellows who said it was a life-changing experience. Simon Critchley said it was one of the most exciting teaching experiences he has ever had (and Simon does not dispense accolades easily).

In the U.S., we are so privileged to move about easily, to go to conferences wherever we like. We inhabit a multi-disciplinary world. But not everyone has that luxury.

What was most striking to me was how the fellows reshaped the Masters’ approach. Those unschooled in Heidegger and those who had been reading his work for years took so much away from Simon Critchely’s close readings of Being and Time. Pat Williams’s seminar on racial formations resonated with what was happening in the world today. Talal Asad’s seminar achieved an intensity of shared knowledge for those who had been studying secularism and those who had been studying Islam.

Julie: In an interview you gave to Savage Minds in December 2014 you quote Raymond Williams and Judith Butler to articulate your vision of ‘critique’. In your opinion, critique is not about judgement but rather, as Butler phrases it, it is “a way of disclosing spaces that are secluded from us”. What are the contemporary “spaces” (imagined or real) you could think of that could apply to this definition? What kind of profiles are you looking for when selecting ICSI fellows?

Stoler: Thank you for drawing attention to the phrase, “Disclosing spaces that are secluded from us.” This, to me, is what the politics of knowledge is in large part about. It calls for vigilance, not revelation; it takes hard work to unthink what too often passes for habit and common sense. The contemporary spaces I think of are obviously related to my own work on imperial formations, as well as racial politics and the ways in which racial distinctions lodge in affective dispositions of “distaste” and “disgust” that we don’t immediately associate as racially inflected. But the ICSI is not confined in anyway to these perspectives. I’m eager for us to address these issues from new vantage points, to attend to ways of knowing that have been disqualified and to understand the strictures of thinking that have made that so.

As for the fellows, we want those who truly want to be here with us, not those who want to make an entry on their resumes. Three of us selected the fellows, independently ranking each one. Invariably, our lists looked similar. When they didn’t look similar, we looked again carefully and revised our list and our thinking. Hopefully, we’ll be able to take the same approach this coming year.

We are looking for a spark in whatever form it stakes, and thus there is no formula for what counts as a good application.

Julie: We noticed that in spite of the fact that the ICSI wants to promote the production of ‘grounded knowledge’, no anthropologist was selected to be a “Master” of the “Master Class” this year. Instead, philosophers seem to dominate the program. This is not to say that disciplinary boundaries matter that much for critical inquiry but the strength of anthropology has always been its emphasis on ‘theories from the South’, as the Comaroff phrase it. Why, as the director of this program and an anthropologist yourself, did you make such a choice?

Stoler: In this initial phase of the ICSI, I decided to call on the diverse and eminent scholars in the New York area. New York City attracts a fabulous range of thinkers from all over the world, with scholars attending The New School, Columbia University, CUNY, NYU, Princeton and Yale. The response has been tremendous. But we don’t want those who can only speak to a small elite, privileged group. That’s too easy and makes for a homogenous mix. The idea is not to stay within the constricted circles of high theory but to generate new conversations across the globe.

Julie: We are asking this question (a bit provocatively) because, as anthropologists, we feel that our discipline is in grave danger of loosing what made its original relevance, namely the translation of alien concepts with the power of decentring Western world views and modes of being. As Da Col and Graeber phrase it in their forword of the first issue of HAU: Journal of Ethnograhic Theory, “Nowadays the situation is reversed. Anthropologists take their concepts not from ethnography but largely from European philosophy—our terms are deterritorialization or governmentality—and no one outside anthropology really cares what we have to say about them. As a result, we have become a discipline spiraling into parochial irrelevance”.

Our concern is then: what will remain of anthropology if our concept work draws from continental philosophy instead of drawing from the vernacular social philosophies we come across through our fieldwork? Is it even a concern of The New School? And what do you think is the added value of anthropology in critical social inquiry?

Stoler: This is not an anthropology institute. I have never worked within anthropology exclusively and would not know how to do so. That said, there are people in anthropology whose thinking and political sensibilities stretch far and wide: Talal Asad, who joins the ICSI in its inaugural year, was a strategic choice. Talal is now on the ICSI’s board of advisors as is Simon Critchely, Patricia Williams, and Jay Bernstein. Simon writes for a large audience, as does Pat. They are not limited by academic protocol, nor its internal debates. In the third year (2017), we will have two anthropologists and more in years to come.

As for the problem with philosophy, I don’t relate very well to this fear of Eurocentrism, though I abhor genuflection toward it. Over the last few years, I have been working on a project and teaching on “Fieldwork in Philosophy” that takes its inspiration from Austin’s first use of the term, Bourdieu’s adaptation and Paul Rabinow’s later revision. Fieldwork in philosophy is a place where anthropology and philosophy intersect—not in order to “borrow” concepts, not in order to adhere to the authorization that philosophy offers and affords, but to think deeply about how conceptual work matters and about resistance to conceptual formulation. Anthropology offers a rich site precisely to disrupt the conventions of what counts as philosophical inquiry and how we do so.

Julie: Agree! And if the ICSI is serious about disrupting the conventions of what counts as philosophical inquiry, why not inviting Davi Kopenawa (the Yanomani shaman, author of The Falling Sky) or other indigenous thinkers to give a Master Class next year?

Stoler: And so it may be!