Libraria is a collective of researchers based in the social sciences who seek to bring about a more open, diverse, community-controlled scholarly communication system. Since 2015, the group has explored alternative funding models for open-access publishing and helped catalyze the Berghahn Open Anthro initiative. More recently, Libraria has launched Cooperate for Open, a demonstration project that seeks to identify opportunities for cooperation among small, scholar-led open-access publications in anthropology and adjacent fields.

This interview with Kate Herman, the newly hired project coordinator for Cooperate for Open, was conducted by Marcel LaFlamme in August 2020. They discussed the distinctive role of independent and experimental publications, as well as the risk of perpetually reinventing the wheel by going it alone.

Could you tell us a little about yourself and about what drew you to the project?

It’s become a bit of a cliché to say so, in both the library and publishing worlds where I spend my time, but I’ve always been a bookworm; as I write this, I’ve just finished a cross-country move that necessitated acknowledging the sheer weight of my book collection! When you spend long enough with your nose in a book you get interested in not only what the author says through the words on the page, but also the means they (and others) chose to convey those words: the form, the format, and all the decisions made in making any text truly public.

Every researcher is adapting to or with the publishing process in their own way, whether adhering to or transgressing from established forms.

After studying anthropology as an undergraduate, I was drawn to academic publishing because I saw that, no matter how deliberately standards and expectations for scholarship are set, there’s always room for experimentation and play—particularly in the humanities and interpretive social sciences. Every researcher is adapting to or with the publishing process in their own way, whether adhering to or transgressing from established forms. For a certain kind of person, this leads to conversations about how the means of publication might better align with the vision that scholars have for their work and its circulation.

Tracking these conversations as they have unfolded in anthropology is actually the subject of the Master’s thesis I’m currently writing. But, over the past several years, I’ve also contributed to those conversations through my work at a small-scale open-access publisher and then a well-loved university press. In these roles, I’ve been drawn into the day-to-day mechanics of publishing, but I’ve especially relished exchanges about the messy, generative possibilities that brought me to publishing in the first place. My work on Cooperate for Open promises to be full of exchanges like this, as I connect with small-scale projects that are playing with the form and function of scholarly publishing. I’m drawn to the challenge of enabling these experiments in an intentional way, rather than sanding them down to fit more neatly into the scholarly communication system as is.

What will the day-to-day work that you’re doing look like?

Right now, I’m drawing up an interview guide for the conversations I’ll be having with our target publications, as well as a data request form that will help us capture some of the fine points of budgets and file formats that editors may not have on the tip of their tongues. We’re really trying to keep the time commitment for each participating publication manageable, because we know that scholar-publishers are juggling a lot at the best of times and all the more so during a global pandemic.

I’m drawn to the challenge of enabling these experiments in an intentional way, rather than sanding them down to fit more neatly into the scholarly communication system as is.

I’m also developing a strategy for identifying and connecting with publications that meet our criteria, which includes doing interviews like this one. (Here’s the plug: if you are working on an open-access publication in anthropology or adjacent fields and are interested in exploring possibilities for cooperation, drop me an email at kate[at]libraria.cc) .

Based on the knowledge that Libraria has built up over the past five years, we have a sense of some broad areas where small, scholar-led publications might think about working together: funding, infrastructure, expertise, and so on. Still, we’re really trying to avoid assuming that we know what the needs and ambitions of these projects are—or ought to be. In a way, that’s one of the distinctively anthropological parts of our approach to Cooperate for Open; our intention is to listen and then over time to look for patterns, rather than starting with an off-the-shelf business model that we’re trying to evangelize.

That said, I think it’s valuable to know how parallel projects in other fields are approaching similar challenges, rather than trying to design structures and processes entirely from scratch. That’s where a bird’s eye view of the scholarly communication system, with all of the different institutions that it comprises, can be useful. So I’ll also be attending events like the annual conference of the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (which is online this year), in order to stay current on the latest debates and developments. I see an important role for networks like Libraria in surfacing the needs of scholar-led publications in a space like this, helping to make their perspectives legible.

How would you respond to a skeptical editor who wonders: “Does anyone actually want or need a study like this?”

Sure, that’s a fair question, and I think I would answer it at a couple of different levels. First, there’s the issue of whether Cooperate for Open speaks to the needs of scholars themselves, perhaps especially those who are heading up the kind of publications that we’re focused on. For me, the “Labour of Love” manifesto that came out over the summer (to which I know that you and Allegra also contributed) offered some insight into the conversations that these scholar-publishers are having with each other.

You see the energy and enthusiasm for starting new projects that can challenge that status quo in one way or another.

Reading that text, you see open access framed as a self-evident good, but one that won’t solve all of the problems in scholarly publishing by itself. You see frustration with a status quo defined by a smallish number of gatekeeper publications on which career advancement comes to depend. You see the energy and enthusiasm for starting new projects that can challenge that status quo in one way or another. But what I especially appreciate is the acknowledgment that it’s hard to keep these projects going, especially when they are standalone endeavors without an established publisher behind them.

I actually think that the last paragraph of the manifesto could stand in as the mission statement for Cooperate for Open:

How can we enable these projects—increase their reach, tap into new forms of support, reduce duplication of effort, ward off burnout and discouragement—while being honest about the drawbacks of their institutionalization? Is it possible for projects like these to share certain kinds of social and technical infrastructure, while retaining their autonomy and the experimental edge that makes them so vital?

In other words, the questions that Cooperate for Open is asking are questions that scholar-publishers are asking themselves. So that’s one indicator of the study’s relevance.

More broadly, my feeling is that the study lines up with priorities that are emerging on the part of other stakeholders in the scholarly communication system. Research funders, who have been criticized for overemphasizing an author processing charge (APC) model of open access that was never a great fit for the humanities and social sciences, are showing signs of greater engagement: there’s a Plan S-sponsored study of collaborative noncommercial publishing models underway that has a number of overlaps with Cooperate for Open.

How can we enable these projects—increase their reach, tap into new forms of support, reduce duplication of effort, ward off burnout and discouragement?

Meanwhile, I see libraries starting to think more creatively about how to support scholar-led open access. The existing templates for this involve either funding a full-service platform like the widely admired Open Library of Humanities or creating an in-house library publishing program. But Cooperate for Open is notable in that a dozen research libraries stepped up to fund an effort to understand the needs of publications that are as yet underserved by these mechanisms. Their willingness to invest in an open-ended process of discovery speaks to a broader appetite for capacity building that I think scholars sometimes overlook.

What do you expect the next steps for the project to be?

Let’s start with the short term: by the end of January, we will have sifted through the data gathered from participating publications and distilled it into some insight on the needs and opportunities in this corner of the publishing landscape. So, I’ll be putting together a report for Libraria and the organizations it works closely with, as well as a summary with key takeaways to share with the community at large. We’re also looking into creating a clearinghouse for some of the more sensitive data provided by participating publications that could be shared internally, as a common asset on which further efforts can build.

But what happens after that really depends on what we learn. One of our guiding principles for this initiative is that it’s possible that there is simply no room for increased cooperation among small, scholar-led open-access publications. If that is what we find, then that’s OK: it’s better to know that than to throw a bunch of resources at creating something that people don’t want. However, I think this outcome is unlikely. What I expect us to learn from the study is in what areas scholar-publishers see opportunities for cooperation and with what degree of intensity. From there, we can start to think about what kinds of partnerships or infrastructures might be needed to advance those aims.

For instance, these publications might benefit from a lightweight knowledge sharing network where best practices could be exchanged. You can imagine a basic listserv or other digital workspace, maybe with a part-time community manager who could chime in when specific expertise is needed. On the other hand, these publications might want to explore working together more closely, potentially forming a cooperative that would seek institutional support as a bloc and perhaps even publish on a shared platform. In that case, I can see Libraria coordinating a funding proposal that would help to get such a venture off the ground.

It’s better to know that than to throw a bunch of resources at creating something that people don’t want.

In the end, the publications that participate in this initiative are not all going to want the same things. So, one last idea that we’ve discussed is facilitating connections between “cohorts” of publications that are facing particular challenges or working toward particular goals. Publishing professionals self-select into interest groups in just this way, but scholar-publishers have fewer opportunities to do so (beyond a handful of networks like Radical OA). From this perspective, the next steps for Cooperate for Open may consist as much in forging social infrastructure as in upgrading technical systems. In my experience, one without the other will only get you so far.

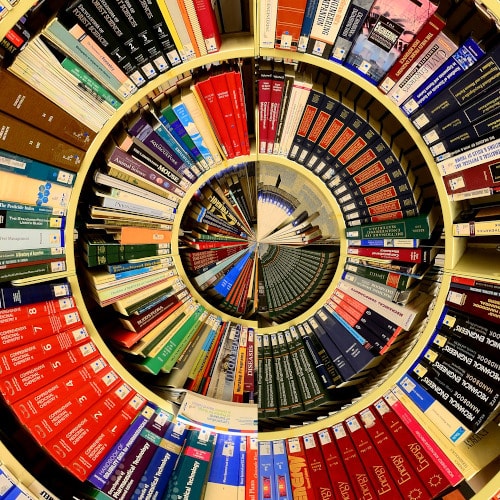

Featured Image (cropped) by pixabay.com