During the ‘Arab Spring’, one of the most puzzling enigmas of al-Wihdat – a Palestinian refugee camp set up in 1955 on the outskirts of Amman, the capital of Jordan – was the ostensible absence of political participation in a place historically known for being a site of political activism and irreducible resistance. My book “Palestinian Refugees and Identity: Nationalism, Politics and the Everyday” (I.B.Tauris, April 2015) analyses the reproduction of nationalism in the context of protracted exile and displacement among young men and adolescents living in the camp.

A very pressing debate that has occupied scholarly and public spheres in and outside Jordan is how Palestinian refugees handle the tension between their integration in Jordan and their commitment to the Palestinian national predicament and the ‘right of return’ (haqq al-ʿawda). Western media and many academic accounts have been generally inclined to believe that ‘Palestinian refugees from the camps’ (laji’in filastinin min al-mukhayyamat) are substantially inimical to any form of integration. Refugees have been hence popularly depicted as inherently political beings, ready to fight and resist all attempts to annihilate their nationalist struggles. In a similar fashion, refugee camps have also been represented as the locus of a political agency based on the ideal of resistance.

Designed as transit centres to host and prepare Palestinian refugees for local integration, refugee camps in the Middle East have become what Julie Peteet has recently described as ‘oppositional spaces appropriated and endowed with alternative meanings’.

In Jordan, there is a widely held collective opinion that camp dwellers have historically nurtured anti-government sentiments. Loyalty to the King, the Hashemite family, and the government is, by contrast, depicted as being associated most clearly with the tribes and Bedouins who are mostly comprised of East-Bank Jordanians. These representations have been simultaneously sustained by historical studies that have documented the rise of Palestinian nationalism in the camps and its challenge to Jordan’s sovereignty. The result is that camps have been portrayed either as places of political instability or as the crucibles of subversive ideas and behaviour.

There is, of course, some truth in camps’ reputation of being bastions of ‘Palestinianness’, irreducible resistance and political unrest. Since the late 1960s, Palestinian national consciousness has crystallised around the iconic figures of the camp and the camp dwellers. When the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) arose out of the havoc of the ‘Six-Day War’, young Palestinians in exile streamed into the resistance movement. During this period of mass mobilisation (1969–82) which came to be popularly known as al-thawra (the revolution), a triumphant narrative of awakening valorised the men and women of the camps as the embodiment of Palestinian resilience and heroism. This was the heyday of al-Wihdat in Jordan and Shatila in Lebanon, and other refugee camps that, like the former, became powerful symbols of Palestinian nationalism. Not anymore a miserable abode for a mass of poor displaced, they came to be known as ‘liberated zone’, the furnaces of the ‘new men’ of the revolution. The ‘sons of the camp’, the Fedayeen, embodied the archetypal Palestinian. The chroniclers of the time portrayed them standing firmly against the overarching forces of their prior submission, no longer brought down by the suffocating impotence and fear of the first period of exile.

In Jordan, the myth of the heroic guerrilla fighter from the camp resonated so powerfully in the collective imagination as to induce the Jordanian monarch, King Hussein, to publicly declare that ‘we are all Fedayeen’.

Camps and camp dwellers were not simply the contents of narratives of heroism. When the various groups that together formed the PLO established their sanctuaries in the refugee camps, these spaces turned into veritable operative bases for the guerrilla fighters. Camp dwellers had become the militant and military backbone of Palestinian nationalism, and the word ‘mukhayyam’ (refugee camp) stood for ‘ma’askar’ (military training camp). Here, the Fedayeen established their headquarters and institutions: their own military police, a civil militia, a corollary of administrative, media, and supply centres, a security apparatus, revolutionary courts, and even trade union movements.

In Jordan, so deep-rooted and powerful was the presence of the PLO in the camps that the government found itself powerless against much of the militant and military activities carried out by the guerrilla groups in the year preceding the Jordanian civil war popularly known as Black September. Unrestricted access to camps favoured the setting of recruitment bases, the provision of militia training and the unfettered circulation of Kalashnikovs and other weapons among guerrillas. There are several good reasons to define the escalating and rapid expansion of guerrilla groups in the refugee camps set up in the host countries as states-within-the-state, especially in Jordan. In the country where most of the Palestinian refugees enjoy full citizenship rights, the emergence of a parallel Palestinian government has encroached on the Jordanian state sovereignty; the consequence of this still reverberates on the very process of national identification.

In Jordan, so deep-rooted and powerful was the presence of the PLO in the camps that the government found itself powerless against much of the militant and military activities carried out by the guerrilla groups in the year preceding the Jordanian civil war popularly known as Black September. Unrestricted access to camps favoured the setting of recruitment bases, the provision of militia training and the unfettered circulation of Kalashnikovs and other weapons among guerrillas. There are several good reasons to define the escalating and rapid expansion of guerrilla groups in the refugee camps set up in the host countries as states-within-the-state, especially in Jordan. In the country where most of the Palestinian refugees enjoy full citizenship rights, the emergence of a parallel Palestinian government has encroached on the Jordanian state sovereignty; the consequence of this still reverberates on the very process of national identification.

Furthermore, if the heroic heydays of the 1960s and early 1970s played, and still retain, a central role in refugees’ political consciousness and self-understanding, a Palestinian nationalistic and potentially explosive sentiment has also been constituted negatively by experiences of loss and marginality. Over the years, Jordanians of Palestinian origin have faced informal discrimination in Jordan at the legislative level (by having their representation in parliament, the Cabinet and the government ministries drastically curtailed) and in the field of employment (especially in the public sector, which largely excludes Palestinians from military and intelligence services). The discriminatory practices of the government and exclusivist claims of a segment of the native population have strengthened among many Jordanians of Palestinian origin the idea of being second-class citizens and, to some extent, reinforced a distinctive sense of community.

Today in their third or even fourth generation away from their villages and homes, most Palestinians in Jordan fiercely uphold their ‘refugee status’ as the only recognition of their rights to be repatriated or compensated.

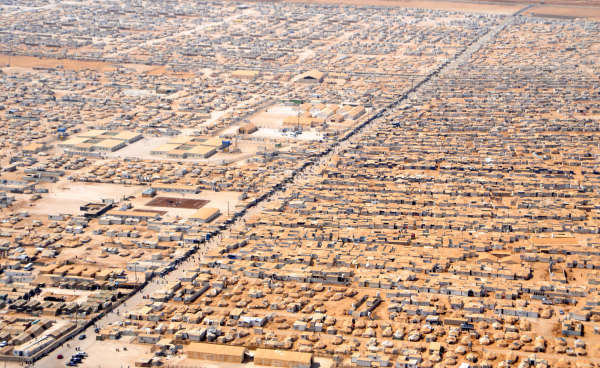

However, camp dwellers’ consciousness in Jordan is not only constituted through the identification with a separate Palestinian entity. It is important to remember that the situation of Palestinian refugees in Jordan differs greatly from their fellows living in other Arab states. Unlike Lebanon and Syria, where Palestinians maintain a legal status as ‘stateless’ persons, Jordan has granted full citizenship to a large number of refugees, and with that, at least in principle, the same rights and duties as any other Jordanian native. The extension of citizenship rights has certainly favoured the emergence among refugees of a feeling of identification with Jordan, the country where they were born and the only physical home they have ever known. On top of that, in Jordan, urban refugee camps are open spaces and commercial areas that more resemble a low-income residential neighbourhood of Amman than a space of exception designed for control and surveillance. Al-Wihdat is not a closed space. Historically, refugees have developed intricate social relations and drawn complex and varying life trajectories by moving outside the camp, returning to it at a later date, or, equally plausibly, never coming back.

After the 1970s, refugees’ political activism gradually terminated in apathy and indifference. Once located at the very heart of the Palestinian national movement, Palestinian refugees and refugee camps in the Middle East became marginalised in the political process. Relegating the status of refugees to the final stages of the negotiations, the Oslo peace agreements were, for refugees in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, clear evidence of how the Palestinian Authority (PA) had sold off the right of return to secure the construction of a Palestinian state . Their exclusion by the official national project has ultimately helped to nurture growing feelings of bitterness and frustration toward political activism and militancy amongst refugees. This disengagement from political participation was furthered by other factors – most notably, the restrictions imposed upon political activity in refugee camps by the authorities after Black September, the discontent with Hamas–Fatah rivalry, and the ineffectiveness of political parties that advocated the Palestinian cause in Jordan.

At the time of my fieldwork in al-Wihdat, neither the recent political turmoil in Gaza and the West Bank, nor the outbreak of the Arab uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East, aroused refugees out of what they described as being their routine life in the camp. The last episodes of ‘uprising’ that most of my informants recollected dated back to 2004 when Jordanian flags were burned in al-Wihdat following the assassination of the historical leader of Hamas, Shaykh Yassin. Interestingly, the issue was eventually solved at an official level by camp leaders (makhatir) who put the blame on alleged agitators coming from outside the camp.

Today, in the aftermath of the ‘Arab Spring’ that has shaken governments, triggered bloody civil wars, and overthrown regimes in the Arab world, a wave of protests have swept across seemingly stable Jordan, but refugee camps remain calm.

As may be obvious by now, the specificity of the Jordanian case challenges popular assumptions implicitly and explicitly reproduced in some academic and journalistic writing on Palestinians today. These traditionally convey the idea of Palestinians’ life as ‘locked in a bind between repression and resistance, ubiquitously struggling for national sovereignty’. In the context of their enduring exile in Jordan, refugees have not only carried out their nationalist struggles but they have also actively pursued socio-economic integration. As I will show, camp dwellers’ apparently contradictory desire of pursuing full socio-economic integration in Jordan and upholding their nationalist struggles brings to the fore the existence of forms of agency and subjectivity that cannot be fully explained by the mutually exclusive logics of ‘resistance’ versus ‘integration’.

I argue instead that young men in al-Wihdat have genuinely subscribed to Palestinian nationalism, but – contrary to common assumptions – they have done so by accommodating this discursive regime to their determination to live in Jordan. The almost non-existence of Palestine’s state institution and the systematic purge of the ‘Palestinian element’ in Jordan’s internal politics has meant that this process of accommodation is not generated through the types of institutions usually responsible for inculcating national values, but through the ordinary activities carried out by people in their daily lives.

In my book, I have chosen to examine spaces of everyday life to examine what type of nationalism is left, reproduced, and transformed amongst people who are today in their fourth generation away from the object of desire, their homeland. Everyday life is an accessible opening through which transformations in Palestinian nationalism can be tracked.

What we will find is that camp dwellers’ assimilation into Jordanian life, the process of ‘becoming-ordinary’, has become the motivation for the emergence of their nationalist ethos, which is less ideological and far more affective.