Leonardo Custódio

Cameras, Narratives and Actions in Favelas of Rio de Janeiro

Complexos (Finland/Brazil 2020) is a 26-minute-long film that was the result of a collaborative partnership between the favela-based filmmaking collective “Cafuné na Laje and me”, a media activist, and Brazilian post-doctoral researcher at Finland’s Åbo Akademi University. The film features interviews by favela-based media activists in conversation with their peers about what activism means to them through the use of photography, poetry, theater, videomaking, and journalism. I had previously interviewed the activists for my doctoral research and wrote a manuscript that they thought would make a great documentary. We secured funding in Finland and produced this documentary during the years 2017-2020.

Release poster of the documentary “Complexos”. Credit: Renato Cafuzo/Cafune na Laje.

The film captures favela activists as they talked, cried, laughed, and expressed the challenges they face, as well as their realistic and utopian hopes. Since many were friends, the conversations captured on film emerged organically and were deeply emotional. They talked about what their craft meant to each of them, and how they used what they knew to benefit the community. They shared memories and described the ways in which they organized collective action that restored a sense of belonging to a place historically neglected by governments and dominated by criminal organizations. They recognized but did not emphasize local problems.

It is, in many ways, a powerful narrative of popular resistance.

I have shown this film in Finland and observed viewers’ reactions. Regardless of the place – the university, activist spaces, and cultural venues – people often displayed a surprisingly empathetic reaction to the film: they seemed to become inspired by listening to and watching favela activists engaged in struggle. Instead of eliciting pity, the film moved viewers to appreciate the value of taking action.

We are as human as you, with problems perhaps worse than yours, but still, we do something. Why don’t you?

I say the reaction of the audience was surprising because I assumed such viewers – privileged people in the (geographic or symbolic) north – often looked at poverty as if poor people were somehow different from them. It had always struck me that pity had become the default emotional reaction to the suffering of poor people, manipulated, in part, by charities aiming to squeeze out tears and donations. The people on screen in Complexos seemed to convey to audiences something different: “We are as human as you, with problems perhaps worse than yours, but still, we do something. Why don’t you?”

Hmm. I might develop a research project on these reactions.

Marie Gorm Aabo: Moved by Sound

I would like to take you on a journey. I invite you to join me, or at least offer you a momentary escape from wherever you are. For the next two and a half minutes, please put on your headphones, close your eyes, and listen to this sound collage titled “Eksperiment 2”.

a world I felt compelled to capture and explore

My recent research on tinnitus made me realize that I was highly efficient at filtering out sounds my mind deemed irrelevant. Unlike my eyes, I cannot simply close my ears. Our minds have a crucial role in sifting through the auditory landscape, discerning the relevant from the irrelevant. During my fieldwork, I also observed that many of my interlocutors had a heightened sensitivity to sound and were more skilled listeners than I was. This inspired me to adopt a more focused approach to listening, akin to the practice of “deep listening”. Initially, it started as a simple exercise to attune myself to the everyday soundscape; unexpectedly, this unveiled a rich world of sounds – a world I felt compelled to capture and explore.

I began to record some of the sounds inspired by my newfound focus. Over the course of a year, I recorded sounds that caught my ear – sounds that evoked emotions, challenged my senses, or took me by surprise. Before long, I had gathered a collection of sounds – short clips lasting a few seconds and longer recordings that went on for several minutes. My collection included sounds from everyday life: cars, machines, water, church bells, people talking, nature sounds, and everything in between.

At home, while I listened to these sounds, they instantly took me back to the place where I recorded them and even the mood I was in at that time. As I immersed myself in these recordings, I could not help but recall Luc Ferrari’s (1970) “almost nothing” (Presque rien No. 1), where he delved into the sounds of a village, transporting listeners to that time and place and establishing a physical connection to a distant environment.

This piece became my inspiration for creating short collages from the sounds I had collected. I took an intuitive approach: I listened to the sounds in my collection and chose a few sounds I thought would work well together, each with unique qualities and durations. I selected 10-15 sounds, put them into an editing program, adjusted their volume, edited their length, and blended them until I had several minutes of a sound collage.

At times, when I listen to “Eksperiment 2” again, I get lost in the sounds. The surprising combinations in the collage never fail to captivate me.

Where did the sounds move you?

Although you might not be able to hear it, in this sound collage we ventured far and wide together: from a nightclub in Oslo to a beach on the island of Møn in Denmark, from a smoky concert lounge in Copenhagen’s Pumpehuset, a hotel room shower in Oslo, a football match, and the heights of a church tower in Kotor, Montenegro – and to my kitchen and to the sea where I grew up.

Meri Kytö

Hörensucht

Kinesthesia can be a bizarre sensation. For example, when you are moving in a vehicle, you do not necessarily sense the movement as your body absorbs the speed and energy of the vehicle. Visual clues are present, but they can be deceptive. We are all born on a moving, rotating planet, yet we still feel that the sun is “going up”, not that we are circling it.

Using technological means, we can move our sensory horizon increasingly further.

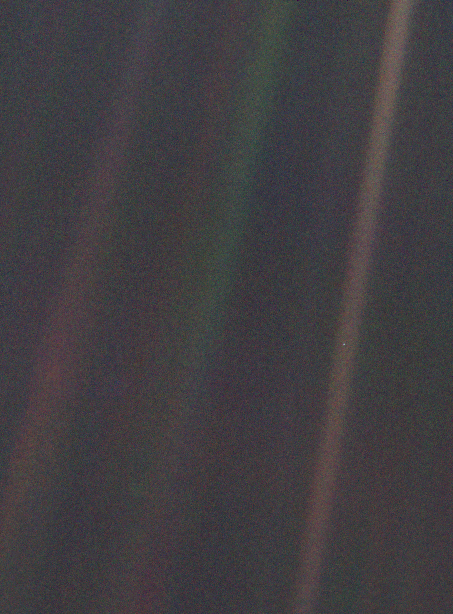

Seeing: Looking at images such as the famous Pale Blue Dot taken by Voyager I in 1990 shifts our position as a viewer. How mesmerizing is it to look at the planet Earth from six billion kilometers away? No human has ever been that far and probably ever will.

Hearing: Listening to recordings from the International Space Station (ISS), we might feel as if we are there, somehow, even though it is hard to imagine floating in space without gravity. The ISS soundscape can be described as an environment of different suctions, pressures, and their equalizations – of pumps and fans, openings and closings. The surfaces are hard. Nothing rolls or bounces. The acoustic horizon is precisely defined by the walls of the station. The hisses and noises tell the story of the life-supporting machinery, and there is nothing beyond the acoustic horizon to expand the soundscape. While listening to these recordings, we become aware of the limited but precise abilities of our bodies.

This translation becomes an extension of sensory perception and thus an extension of embodiment.

Instrumentally enhanced perception and instrumentally translated perception (Ihde 2016) are two distinct ways that non-astronauts can experience outer space through various media. An instrumentally enhanced perception is produced, for example, by a recording that has been temporally modified by compression or extension. Similarly, it can be produced when the vibrational properties have been clarified to represent the desired signal; for example, by condensing, manipulating frequencies, or raising and lowering pitch. The object observed conveys its isomorphism: the shape of the sound event is still recognizable. In comparison, the premise of instrumentally translated perception is that perception is “translated” from one sense to another; for example, from image to sound, or from a phenomenon beyond human sensory perception to an image. This translation becomes an extension of sensory perception and thus an extension of embodiment. In these cases, the perception has to be “read” because its form is not recognizable. For example, when an oscilloscope draws a picture of a sound, the sign system of this picture must first be learned and read in order to form a supported understanding of it. Other familiar examples of technologies that indirectly translate perception include metal detectors, geiger counters, and compasses (Ihde 2016: 38-40).

Space technology is strongly associated with “machine dramatics”, which include experiences of the technological sublime and the colonialist narrative of frontier, exploration, and taming the new (see Suominen 2003, 34). The longing to see (Sehensucht) in the early Romantic period produced an almost compulsive need to peer beyond the everyday environment. Hiking, alpinism, observation towers, and hot-air balloon trips brought the adventurous bourgeoisie an experience of the sublime (Huhtamo 1995, 103). An imaginary space journey made by listening to recordings produced in or from outer space is akin to this interest and curiosity. Let it be called Hörensucht: listening to the acoustic horizon beyond, in all its out-of-reachness and virtuality.

References:

Hadfield, Chris. 2020. “ColChrisHadfield”on Soundcloud. https://soundcloud.com/colchrishadfield, accessed 29 Aug 2024.

Huhtamo, Erkki. 1995. “Ruumiiton matkustaja ‘ikään kuin’ -maassa”, in Virtuaalisuuden arkeologia. Virtuaalimatkailijan uusi käsikirja, edited by Erkki Huhtamo, pp. 88-125. Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopisto.

Ihde, Don. 2016. Acoustic Technics. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Suominen, Jaakko. 2003. Koneen Kokemus. Tampere: Vastapaino.