You know how a common criticism of politicians is that they’re out of touch with the real world? “Does your local representative know the price of a carton of milk in your area?” How the Guardian is often criticised for speaking too much to a middle-class readership and ignoring more working class realities? Well, this post will make the argument that advertisements are also somewhat out of touch with the real world. To this end, I’ll be interrogating some of the in-visible, implicit values within the frames of a Lebanese nuts ad. My home town is indeed as trendy as the ad portrays, but it’s worth engaging with how the ad represents (constructs / plasticises) certain realities and what it leaves out of frame.

First, some conceptual departure points.

It is, or at least by now it should be, clear that advertisements brand producers and consumers more so than products. See Baudrillard (1981) on sign value (the social status attached to our consumption of objects), Hennion et al.’s (1989) early work on mediation (how ads mediate our own sense of self) and more broadly Bourdieu (1986) on distinction (how we strive to create greater distance with those ‘below’ us and less distance with those ‘higher up’).

It makes sense, too: When we buy things, we buy them not for what they do but for how they ‘construct’ us.

Otherwise we’d all be walking around with Adibos sneakers and unbranded black bags, because what is the difference between Adidas and Adibos? Those two letters, that’s what. Better quality? Not if we think of price-quality ratio. Better design? I rest my case. Advertisements, their products, and their situated-ness in our everyday lives, brand us. Granted, there are other social forces that shape us too, but let’s stick to ads for the time being.

Remember, though, the “us” that advertisements brand is not a homogenous group, rather a stratified and diverse collection of people with their own baggage (situated experience). Some of this baggage is structural (social structure), some of it individual (agency), but you get the point.

Peoples’ lives vary, though. While talk of a creative class is rightly placed inside a box that has “Pop sociology” written all over it, it’s worth remembering this variance: the everyday life of an insurance salesperson, for example, is very different to that of a director of photography. They have different routines, different problems, different joys. And this difference is key. It’s a bit like setting agendas: ad producers set the agenda and consumers are attendees at the conference, if you will. Ads are imbued with the visions of their producers, not insurance salespersons. Hennion et al (1989) call ad producers “artisans of desire,” framing and making visual what we as consumers come to desire. Tiny side-note here that this does not contradict any of the ‘prosumption’ theories (that consumption itself is an act of production): we are still ‘re-producing’ or ‘prosuming’ an initial product.

The second post on this thread argued that images construct social worlds and that these constructs should be questioned, showing the co-constitution of tourism ads and national identity. By that same token, advertisements set the boundaries and frames for the things we want to be. Think of it this way: Rihanna wearing Pumas and doing dance practice – when you buy those sneakers you’re buying into a want to be as cool / on it / fit / stylish as Rihanna and / or Puma.

You want to be those things, but what you want has been shaped (not determined) by those frames.

There is a disconnect between the paradigms in which these social worlds are framed and constructed, and between the empirical realities and situated experiences of those consuming these constructs. Like I said above, situated experience varies. It’s a bit like you wanting dolls deep down inside as a kid while your family keeps getting you construction sets, toy guns and video games. Even though you still enjoy these toys, the fact remains that what’s offered is disconnected from matters to you.

Right. Now to shedding light on and interrogating the implicit, in-visible assumptions, values and wants embedded in all things visual (actually, just ads): In Lebanon, we make great ads. We make great visuals, not just ads. This nut ad from 2014 being a case in point.

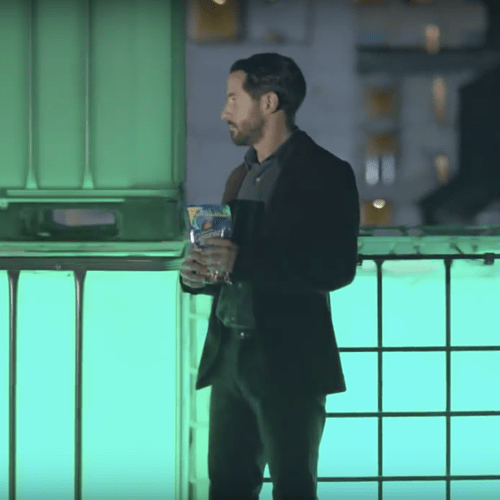

So here you are then, you young Lebanese dude. Congratulations on the new flat, evidently a traditional one (we have a big thing in Lebanon, and rightly so, about preserving our traditional architecture – ‘Save Beirut Heritage’ – google it). Your dad has helped you move in, so you’re single. Your parents are progressive enough not to expect you to live with them until you get married, because he’s agreed to help you. You’re excited, but a little bit lost. You’re also a family man – your dad helped you move in, not your friends.

Your neighbours invite you to a meeting (not a party). You open the door and realise that some of them might be very interesting indeed. Now you actually want to go to the thing. The white line on your black sneakers suggests you’re just the right blend of cool and beige for the maximum subset of Lebanese men (and women) to identify with you on some level. I mean, who doesn’t want to be the new owner of a traditional Lebanese flat with beautiful neighbours? Mini side-note for those of you who still don’t know what “Yalla” means, it’s “Come on.” Also, “Habibi” means “My Love” but we use it very freely.

Notice how the old people are excited about the meeting and seem up for a party. Perhaps the only thing real about their characters is that they’re excited about the meeting. They are ideal types, constructed and framed after sanitising and plasticising whatever redeemable qualities your average older Lebanese man has.

Once on the roof (where the meeting is being held), you see your ideal typical representation of Lebanese society. There’s a happy bureaucrat who is so not corrupt that he even uses the hole-puncher thingy to confirm your attendance. He contrasts completely with the stereotypical civil servant in Lebanon: they would have clocked in and then left their desks for that other private sector job they hold (two salaries are better than one). If they were at their desk they’d probably ask for your ID and other assorted official documentation until you slip some cash with that entry ticket of yours.

In the next frame gender-roles are turned upside down as the men gossip about the new kid on the block. Things are then pulled back to the norm with the typically-unable-to-smile-patron-dad-type-figure on the table. The meeting is actually a party, it turns out, and that’s great. All meetings should be like that.

It’s a sanitised party, though. No clear references to alcohol, any of our 18 sectarian groups or the other few groups who have no official recognition. No hijabs, no Elies, no Mohammads, only Karims, Fuads, Miras and Chantalles (names that don’t signify religious background). Nothing divisive, just a proper rooftop gathering with your neighbours.

Everything is in a happy medium: the sort of stuff an alcoholic would relate to just as much as a pious person. Whose happy medium is this, though?

The scene with the neighbours is also significant. Sobhiyyé is a big thing where I’m from. It’s when people visit each other for morning coffee. We also have Asrouniyyé, which is the afternoon, post-siesta equivalent of morning coffee, usually with an added snack that should not, and cannot, be refused.

And then, the return of the flirt, juxtaposed with the backgammon: another happy, sanitised fight-free marriage of tradition and modernity ‘a la Libanaise’. It’s tough to find older men who are happy to dance in Lebanon. I have a pet theory that their generation has not been socialised into being comfortable with happiness (you can’t blame them, though, considering all they’ve been through and all they’ve put others through). To illustrate, every time (literally every single time) there’s a happy occasion for which the whole family is gathered, they seem to take turns to find a secluded space for themselves, cry out their happiness, and then return to the table. There’s a lot in that scene of the backgammon-watcher shaking it. He is happy and proud of it. We all want that: for our dads and grandfathers to let go every once in a while. They want that too, I’m sure.

We have power cuts in Lebanon. At least three hours a day in Beirut, and more outside of the capital city. We have apps that tell you when to expect the next power cut. It’s quite frustrating, still, especially in the summer, and especially for people who can’t afford / refuse to subscribe to private generators. See, our politicians make a lot of money on the side from their private generator businesses (thus the lack of 24 hour electricity in the 21st century). But it doesn’t have to be this frustrating, as the ad shows.

Another sanitised plasticisation of everyday life in Lebanon, with the negatives all weeded out.

The implicit message seems to be: do you want a happy Lebanon? A Lebanon where Beirut heritage is preserved, where your neighbours are hot and their angry parents absent, where old men are happy to show their happiness, where geeks are not self-conscious about their dancing, where stereotypes of gossipy women are no longer gendered but shared (because we don’t want to lose the tradition of gossiping, obvs), where people are so comfortable that they have the time, energy and resources to throw an awesome rooftop party complete with lit, modern furniture, bartenders, backgammon, a bureaucrat, and where attraction and sex are reserved for when the lights go out? Yes? Here, then, have these nuts.

You’re not buying the nuts, though, you’re buying that Lebanon. I really don’t mean to be critical about the ad here, just to pull apart some of its invisible constitutive elements: Whose assumptions, values and wants are these? Anyone can relate to the ad, that’s for sure, but whose ideal is the ad asking us to relate to?

The relevance of such values and ideals is falsely assumed on the part of producers, and the reality of the matter is that they are often insignificant to most consumers (aka people). What’s relevant to producers of rhetoric or aesthetic is relevant to a privileged minority of the whole social fabric, a contingent relevance that Bourdieu tells us reifies the distance between ‘us’ and ‘them’. There is a normative case being made for a better Lebanon here, and in a way that is what’s being sold, but it’s a normative case from the perspective of a privileged few, that excludes the underprivileged many.

Think of it this way: how many of the characters in that ad do you think know the price of a local carton of milk? My sense is that most don’t, because they send their migrant domestic workers to buy their milk (and we don’t see these people in the ad because they’ve probably been told to stay at home).

I’m not arguing that ads specifically and the visual more generally should construct more accurate, realist representations of society, or that ad producers should do an ethnography of poverty before shooting a frame. It’s just worth engaging a little bit critically with the social worlds that ads construct.

Indeed, many of these values and assumptions are no longer invisible: ad agencies and producers increasingly see themselves as agents of social change (thanks Editor!), but this should be approached with caution. Rosalind Gill (2012, 2009: 149) talked about how feminism was appropriated by ads, its political significance hollowed out and its critique of gender relations domesticated. This is her quoting Susan Douglas: “the appropriation of feminist desires and feminist rhetoric by Revlon, Lancome and other major corporations was nothing short of spectacular. Women’s liberation metamorphosed into female narcissism unchained as political concepts like liberation and equality were collapsed into distinctly personal, private desires (1994: 247–8).”

There’s a similar trajectory here: multiple visions of a ‘better Lebanon’ hollowed out of their politics and a creative, privileged iteration of these sanitized, plasticized, framed and disseminated for consumption. The issue with this is two-fold: first, it defines and imposes (by virtue of agenda-setting) particular processes in pursuit of distinction (towards Lebanese men who are comfortable with emotion, for example), thereby re-excluding realities of the under-privileged. Secondly, it shifts debates around this by now politically hollow better Lebanon towards more privileged registers: subscribing to a private power generator becomes the norm, hollowed out of the more relevant politics of “are private generators really that profitable to our politicians to the extent that no one can be bothered to fix up our power supply issues in government?” In other words, it’s not that politics is vacuumed out of these debates per se, rather that this politics is reframed and reconfigured (thanks, capitalism) to privileged frequencies over under-privileged realities. Donna Haraway and standpoint: people with less power have so much power done onto them while the powerful deal with their first world problems.

As the previous blog post in this series details, Images do indeed matter. This one tries to add to that: the values, assumptions, invisible perspectives and intentionalities underlying images matter too.

References:

Baudrillard, J., 1981. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. Telos Press.

Bourdieu, P., 1986. Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Douglas, S.J., 1994. Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female With the Mass Media. Random House Incorporated.

Gill, R., 2012. Media, Empowerment and the “Sexualization of Culture” Debates. Sex Roles 66, 736–745. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-0107-1

Gill, R., 2009. Beyond the `Sexualization of Culture’ Thesis: An Intersectional Analysis of `Sixpacks’,`Midriffs’ and `Hot Lesbians’ in Advertising. Sexualities 12, 137–160. doi:10.1177/1363460708100916

Hennion, A., Meadel, C., Bowker, G., 1989. The Artisans of Desire: The Mediation of Advertising between Product and Consumer. Sociol. Theory 7, 191–209. doi:10.2307/201895