The bulky and weirdly shaped package I hold in my hands weighs nearly 20 pounds. 20 pounds of memories materialize in a final leaving present that now makes going away feel even harder. I struggle trying to give the impression of it being much lighter, but I have started to worry that customs might take it away from me. Needless as it turns out when the woman at the check-in that screens my bags – including this particular piece of hand luggage – just smiles and tells me that I made a good decision taking lots of shoki shoki (a type of lychee) home as a present.

The shoki shoki were one of many gifts I was sent off with by people I got to know as friends and informants over the past 18 months of my fieldwork in Zanzibar. The sister of one of the children I worked with at a madrasa (Qur’an school) decorated my hands with Henna as is custom before celebrations or journeys. A friend who works as an artist and architect came to give me two drawings of the house I had lived in for the past year which we always sat outside of talking for hours. And a woman from one of the communities I worked in spent three hours with her daughters baking a specific cake for me – and starting again from scratch twice while I sat next to her feeling embarrassed and humbled at the same time – until she decided it was “good enough” for me to take home.

These goodbye presents were more than gifts. They made me realize the depth of relationships I had been able to form in ways that went beyond researcher-informant interaction. They were labours of kindness and generosity, yet deemed natural, to send me off on my journey home.

Looking at fieldwork itself an act of travelling makes the moments of arrival and departure key, and juxtaposing them now – post fieldwork – makes me feel like I have travelled to far more than one place during this time. I feel like constantly having left and resettled even though I spent 18 months on only one small island. Still, the new spaces which with time lost their unfamiliarity and became something in the wider sense of home, were less geographically bound and lay rather within the people that constituted my experiences. Primarily I locate these spaces with the 60 children from 4 primary and 2 Qur’anic schools whom I worked with throughout my field research.

Flashback: Sensory Childhood Research

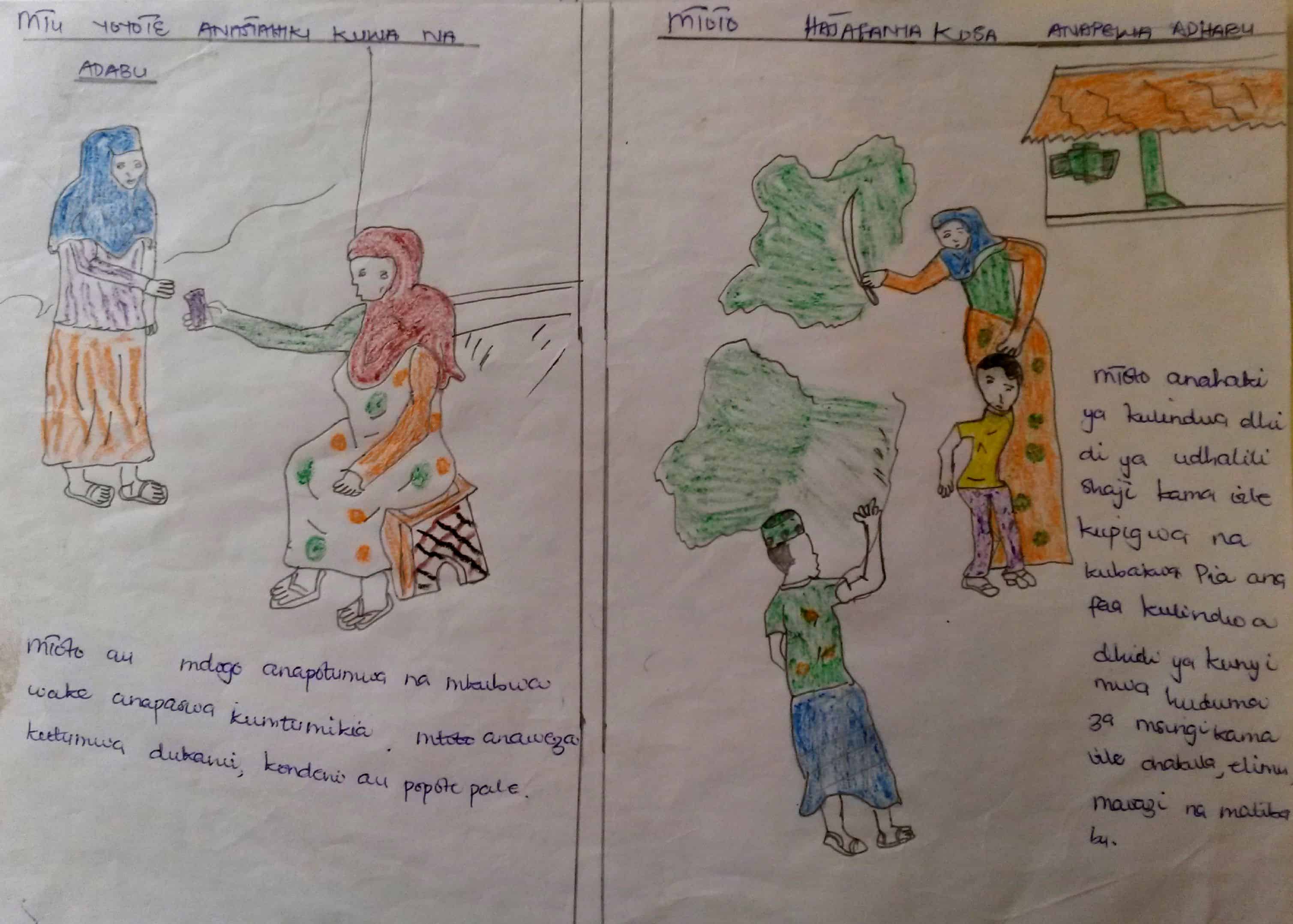

In Zanzibar my aim was to explore the different meanings that children and their adult counterparts (like parents, teachers, development workers) attribute to the wider notions of childhood, manners, punishment and safety in their daily lives. I approached my research questions through the use of child-friendly research methods such as “photovoice” and “draw and write”. My use of these methods turned out to reveal much about the social system children live in and their relationships with adults. The conditions under which these methods were applied proved to be as important as the approach itself as children’s participation and agency remained dependent on the actions of the adults in their lives and showed to be a rather relative and fragile concept. All stages and spaces of working with these approaches were mediated by adults and had to be negotiated in reference to them. As much as I had intended to put children at the centre of my research, my methodology proved how inseparable they were from the adults in their lives and how I would have to consider them both. The presumed adequacy of my methodology for my project was challenged regarding this inevitable adult presence and influence. Reaching the aim of giving the children the chance to take a lead in the research themselves and to emphasize their usually sidelined voices (Wang 2006) was not immediately guaranteed. The following example shows this clearly.

“You really want this picture developed?” the guy in the photo shop asks me, when I point at the image that he critically examines on the screen of his photo print machine. I tell him “yes, I would like all pictures to be developed, every single one”. He seems confused and asks again, pointing to the next photo that has turned out similarly dark and out of focus. “But these are bad photos, you cannot see anything. My boss told me to only develop the good ones”, he responds to my question about why half of the children’s photos that show on the negatives have not been developed.

“This photo shows a student being punished by being hit” (Picha hii inaonesha kuwa mwanafunzi anapewa adhabu ya kupigwa) is what the 14-year old photographer wrote on the back of his photograph.

The image was taken as part of one of the photovoice workshops I conducted with children in primary and Qur’an schools.

The children’s images became personal accounts of their everyday lives which were not biased by my physical presence as a researcher and would not have been accessible to me in any other way.

They showed a variety of scenes ranging from moments of play to actual situations of physical violence. My research participants themselves chose the photos they would want to be included in the research and explained to me what each one showed. The two ethnographic vignettes show that regardless of how clear and meaningful the above picture’s message seemed to the child-photographer and to myself, it was not immediately obvious for other people involved at different stages of the research process.

My experience with a “draw and write” approach was similarly challenging, but more in regard to children’s limited familiarity with drawing as a task of self expression. Another challenge was children’s and teachers’ lack of familiarity and hence discomfort with creative arts as the curriculum neither includes arts or music classes, as these are often considered haram – forbidden according to Sharia/Islamic law. Where the drawing part of the research activity only offered partial perspectives onto children’s viewpoints and could not be considered an adequate “substitute for children’s voices” (Mitchell 2006: 69), the writing activity added valuable insights. What turned into a great opportunity here was that children would dare to voice their opinions in a very different way than when I would sit down together with them. Many of the children I worked with were extremely shy to speak their mind, especially in a critical way. This shyness or restrained is highly valued in Zanzibari society and hence perceived as necessary to adhere to by most children to avoid punishment, but of course rather hindering in an attempt to gather their views. Here, especially writing poems – a respected skill in Zanzibari Swahili culture – and within that the recreation of the social order they live in, turned out to be an insightful way into their lifeworlds and views of protection and personhood.

Entering Liminality and Relocating the Mind

Research journeys consist of many attributes, which the recent #fieldwork posts at Allegra all showed in different ways. Now, as I move in between my field site and back to my academic home in the UK, my identity and self-representation as a researcher shifts. Baginova’s thoughts on the relevance of certain footwear for her research reminded me particularly of consistently wearing a veil for the past 18 months, and it now not being an unquestioned part of my daily dress. With similar ease I could relate to Tawasil’s discussion of her relationships with her informants and friends in the field, and to Swamy’s reflection on maintaining the border in between professional and personal identity and its influence on scholarly analysis.

Instead of defining my research journey as a process with a clear end-point, it seems to consist of different stages of reflection – the current post-fieldwork stage being one of them. Disorientation is probably the most fitting description of this state, where I no longer am the researcher in the field and not yet have completed the whole process of the PhD project. More than 4000 miles away from my field site, my ethnographic journey still feels far from completed.

I relocated my body, moved it away from my field site, but find my mind catching up only slowly.

I am in the in-between – I have entered liminality (Turner 1970). I suddenly am out of touch with my research participants when engaging with them had become a kind of routine. This everyday research routine now has to be transformed into a more distant way of analytical thinking, away from the field, about what happened during the time in the field. My “fieldwork self”, the researcher, has merged with my “everyday-self” and I struggle making a distinction as I am still the researcher with the same questions and ideas but now again in a different space that mirrors those ideas in other ways than my field site could. I know that this uncertain state will dissolve eventually, once I will fully reintegrate in the structured academic world, but while I’m waiting for this to happen, it is the space that connects me with both the field and the non-field, my field- and desk-researcher selves.

Rethinking Child Protection Programming

The distance between me and the island will create a new space for thought and for doing what I set out to attempt: to reconsider the way child protection programming is currently done. ‘Child protection’ interventions in Zanzibar have contributed to establishing a symbiosis of co-existing systems of thought about childhood and safety. While following my main research themes of protection and personhood by working with children and adults, there were three different discourses that kept overlapping: the international aid discourse, the religious discourse, and the Swahili socio-cultural discourse. These discourses proved to be critical in structuring people’s narratives of “child protection” and made sense of what it means to be a child and to be safe differently. Answers to seemingly simple questions like Who is a child? became more complex when, for example, the international aid discourse considered everyone below the age of 18 to be a child, but the socio-cultural discourse would mark the end of childhood between the age of 12-15 with the onset of puberty (kubaleghe). Such differences are often ignored as they might seem irrelevant to policy makers or, more often, as they require extra time for contextualizing interventions which is usually limited in the development world that has to stick to log-frames and budget lines. Nevertheless taking into account information “about the ways children actually live in their communities, as well as local beliefs about childhood” (Ennew 2002: 350) is exactly what those in charge of policy- and programme-making for children should consider to do more.

What often falls short in this context is the fact that child protection as well as child disciplining practices are also embedded in cultural and religious values and play a role in the achievement of social personhood. Individuals – both adults and children – exist in social and historical contexts that cannot be ignored (Crewe 2010).

There is a need for recognizing, respecting and integrating all of these conceptualizations in contextualized “child protection” programmes, instead of simply overruling religious and cultural ideas with universalized standards.

As through the lens of medical anthropology, “everyone may share the same elements from which diagnoses may be made and therapies initiated, [but] each person can have a slightly different view of how categories fit together, and, therefore, of how the illness can be best progressed to cure” (Davis 2000: 69). If we consider harms to children’s lives, i.e. illnesses, abuse etc. as curable, what is necessary in child protection programming is “to see into the social circumstances surrounding an illness and to give them definition” (ibid.: 103) – to the social circumstances surrounding harms to children’s lives in Zanzibar and to create a contextualized response to them. Instead of further “rendering technical” (Li 2007: 123) social problems like violence against children, these should be “rendered intelligible” (Davis 2000: 103) and hence more likely to be “treatable”.

All photos in this post are courtesy of Fanziska Fay.

References

Crewe, Emma (2010) Protecting Children in Different Contexts: Exploring the Value of Rights and Research. In: Journal of Children’s Services, Vol 5 (1), pp43-55.

Davis, Christopher (2000) Death in Abeyance. Illness and Therapy among the Tabwa of Central Africa. Edinburgh University Press.

Ennew, Judith (2002) Future Generations and Global Standards: Children’s Rights at the Start of the Millennium. In: MacClancy, J. (ed.) (2002) Exotic No More. Anthropology on the Front Lines. University of Chicago Press, pp338-350.

Li, Tania M. (2007) The Will to Improve. Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Duke University Press.

Mitchell, Lisa (2006) Child-Centered? Thinking Critically about Children’s Drawings as a Visual Research Method. In: Visual Anthropology Review, Vol 22 (1), pp60-73.

Turner, Victor (1970) The Forest of Symbols. Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Cornell University Press.

Wang, Caroline (2006) Youth Participation in Photovoice as a Strategy for Community Change. The Haworth Press.