During my research on Sierra Leone’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) 2003, a group of men in Lunsar invited me to a palm wine bar to hear their views. They were especially annoyed about the absence of “benefit” – material compensation – for those who testified before the TRC. “How will I go and talk on the radio about what they’ve done to me, when I get no benefit from that?” asked one young man. But despite being told that the TRC would not compensate anyone for their “truth telling,” most of those who testified before the TRC’s District Hearings still hoped that it would. Again and again, after narrating their memories of violence and ongoing experiences of loss following Sierra Leone’s devastating eleven-year war, they asked for help from either the government or the TRC itself with food, housing, education, and medical care (TRC, Sierra Leone 2004, Vol. 2: 235, para. 31). After the TRC, broad expectations of material assistance merged with expectations of compensation for testimony itself (Millar 2010, 2011; Shaw 2007, 2014). The absence of such compensation was a common complaint among those who had testified. For the Commission, these expectations were “misunderstandings” of the TRC’s mandate, and of the reparations process it recommended. But what if we take these expectations seriously:

What does it mean to claim that truth telling is a task – a labor – for which the teller should be paid?

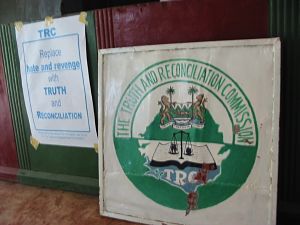

These claims translate “the labor of memory” into literal form. For Cole (1998; 2001) and Jelin (2003), the labor of memory denotes an active process through which people change their relationship to the past and rework the social world. Legal and human rights activists, I suggest, also translate the process of memory work into literal form, but tend to do so by mechanizing and fetishizing it. Activists claim that truth telling transforms social and political reality by producing a specific set of outcomes. But they typically cast this as a process whereby a specific kind of memory – the act of testimony and its dissemination through print and electronic media – produces accountability, reconciliation, and peace in the manner of a fetish object (see Comaroff and Comaroff 2006), since they represent these causal “outcomes” as inhering within truth telling and truth commissions themselves (the latter termed, tellingly, a transitional justice mechanism). When Sierra Leone’s TRC began operations in 2002, for instance, posters in Freetown and major provincial towns announced: “Truth Today…Peaceful Sierra Leone Tomorrow.”

The expectation that the performance of such memory “work” in a truth commission should be compensated may sound startling. Truth commissions are, after all, defined as victim-centric mechanisms that are assumed to give victims “voice” (Ross 2002) and to address their needs. Thus Sierra Leone’s Truth and Reconciliation Act states that the TRC’s function should be “to work to help restore the human dignity of victims and promote reconciliation by providing an opportunity for victims to give an account of the violations and abuses suffered and for perpetrators to relate their experiences” (2000: III.6.2b). But whether the thousands of people who have, over the past few decades, recounted their memories before truth commissions benefited from their truth telling has been repeatedly called into question (e.g., Kelsall 2005; Laplante and Theidon 2007; Millar 2010 and 2011; Ross 2002; Shaw 2007 and 2014; Theidon 2012; Wilson 2001; Yezer 2008).

Their memory labor – if not exactly abstracted – has been harnessed, we might argue, to the fetishized deployment of truth telling in the post-conflict “machinery” of peacebuilding.

This point requires us to situate the work of truth telling within the post-conflict economy. Sierra Leone’s civil war (1991-2002) was in large part “about” labor, since it had its roots in a history of struggle over young people’s labor. War is often viewed as a singular period of rupture, and “post-conflict” as an exceptional period of transition in which the body politic is cleansed of the past (Castillejo-Cuéllar 2014; Rojas Pérez 2008; Vigh 2008). But armed conflicts unfold within longer histories of violence, which rarely disappear at the official end of a war.

In Sierra Leone, eleven years of civil war were layered upon a thirty-year legacy of state violence, ongoing structural violence, and much deeper memories of colonial rule and slave trades (Ferme 2001; Shaw 2002). In particular, young people’s social marginalization, the extraction of their labor by rural gerontocratic elites, their struggle for education and resources, and their predicament as perennial dependents in a nation-state characterized by a collapse of opportunities all configured the war and its aftermath (e.g., Peters 2011; Richards 2005).

For many young people who became combatants, either as conscripted abductees or volunteers, the civil war had opened up opportunities, although these were violent and dangerous (e.g., Hoffman 2011a and b; Peters 2011). As Hoffman puts it, ‘[t]o fight was not so much to take on the enemy as to take up a labor, to work’ (2011a:40), through, for example, agriculture, diamond digging, porterage, domestic labor, and fighting. When “peace” came in 2002, it meant a transition to an unfamiliar and unstable postwar economy. Internationally funded interventions became the new economy – but one that was opaque and unpredictable (Fanthorpe 2003).

The impoverished majority, both young and old, experienced “peacetime” as a continuation of their struggle for viable lives in a new environment that shared many qualities, such as volatility and violence, with wartime.

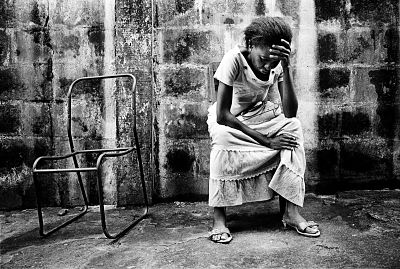

As one of my interlocutors, Adama Koroma, put it at the end of her testimony before the TRC, “I cannot be struggling and say that I am living in peace.”

Participation in Sierra Leone’s TRC was located in the relationship between these two economies of war and post-war. In a radically uncertain and constantly shifting social environment, Sierra Leoneans emerging from more than a decade of war explored any opportunities that presented themselves. For many people, the post-conflict economy of humanitarianism and peacebuilding became a potential site of resources for the creation of “post-conflict” lives. In order to enter this economy, they sought to construct relationships with NGOs and the TRC. This meant, in the case of the TRC, learning to narrate memories of wartime violence as “truth telling” in written statements and oral testimony before the Commission.

Truth telling became a new work of memory in Sierra Leone, based on a new conceptualization of what memory could do – namely, open up a route of redress and reconciliation that would unlock a future of national peace.

It also integrated memory into a neoliberal discourse of responsibilization (e.g., Trnka and Trundle 2014), in which individuals were encouraged to assume responsibility for reconciliation and peace through the truth telling.

In addition, it connected memory to ideas of humanitarian suffering (e.g., Fassin 2011) through a rhetoric of victimhood that is especially pronounced in transitional justice. Narrative memories of suffering, loss, and injury thereby became the vehicle for the TRC’s recommended reparations program. At the end of their testimony before the TRC, people were invited to make recommendations for the government, which, the TRC claimed, the government would be compelled to fulfill. Yet more than ten years after the war ended, the very limited reparations program the Commission recommended has been only partially and inadequately implemented (Conteh and Berghs 2014). Thus over time, people’s continued struggles for lives and livelihoods marked the limits of truth telling as a failure of memory.

But requests for material assistance via truth telling were not always presented in terms of the language of suffering and victimhood. Like Laplante and Theidon’s interlocutors in Ayacucho, who viewed reparations after Peru’s TRC in terms of “implicit contracts” and rights (2007), those who had testified before Sierra Leone’s TRC recast the language of victimhood. They spoke instead of (failed) reciprocity, re-routing the claimed connections between truth telling and national peace and reconciliation through a path of labor and compensation. For them, memory “work” was more than a figurative concept. They had enacted a task – and one that was emotionally difficult – which they had been asked to perform for the sake of their country. And they wanted to be paid.

This re-routing has a significance that extends beyond the clear need for economic justice and reparations. It reframes transitional justice within the contradictions and intersections of post-conflict economies, revealing the ways in which participants’ struggles for post-conflict lives in conditions of structural violence and impoverishment inflects every aspect of their participation in transitional justice mechanisms. In so doing, these struggles reshape the work of memory and the meanings of “justice” and “peace” long after these mechanisms have been dismantled.

Main Image: © Pep Bonet (City of Rest / Sierra Leone 2006 – 2007), Creative Commons License

***************************************

Works Cited

Castillejo-Cuéllar, Alejandro. 2014. Historical injuries, temporality and the law: articulations of a violent past in two transitional scenarios. Law Critique 25:47-66

John L. Comaroff and Jean Comaroff (eds.). 2006. Law and disorder in the postcolony: an introduction. In Law and Disorder in the Postcolony, pp. 1-56. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Cole, Jennifer. 1998. The work of memory in Madagascar. American Ethnologist 25:610-633

Cole, Jennifer. 2001. Forget colonialism? Sacrifice and the art of memory in Madagascar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Conteh, Edward. and Maria Berghs. 2014. ‘Mi at don poil’: a report on reparations in Sierra Leone for amputee and war-wounded people. Draft report, Amputee and War-Wounded Association, Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Fanthorpe, Richard. 2003. Humanitarian aid in post-conflict Sierra Leone: the politics of moral economy. In Sarah Collinson (ed.), Power, Livelihood and Conflicts: Case Studies in Political Economy Analysis for Humanitarian Action, 53–66. HPG Report 13. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Fassin, Didier. 2011. Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press

Ferme, Mariane C. 2001. The Underneath of Things: Violence, History, and the Everyday in Sierra Leone. Berkeley: University of California Press

Hoffman, Daniel. 2011a. Violence, just in time: war and work in contemporary West Africa, Cultural Anthropology 26: 34–57.

–2011b. The War Machines: Young Men and Violence in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jelin, Elizabeth. 2003. State Repression and the Labors of Memory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Kelsall, Tim. 2005. Truth, lies, ritual: preliminary reflections on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Sierra Leone. Human Rights Quarterly 27:361-391

Laplante, Lisa J., and Kimberly Susan Theidon 2007. ‘Truth with consequences: justice and reparations in post-truth commission Peru’, Human Rights Quarterly 29: 228–50.

Millar, Gearoid. 2010. Assessing local evaluations of truth telling: getting to ‘why’ through a qualitative case analysis. International Journal of Transitional Justice 4:477-496

–2011. Local evaluations of justice through truth telling in Sierra Leone: postwar needs and transitional justice. Human Rights Review

Peters, Krijn. 2011. War and the Crisis of Youth in Sierra Leone. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press

Richards, Paul. 2005. To fight or to farm? Agrarian dimensions of the Mano River conflicts (Liberia and Sierra Leone). African Affairs 104:571-590

Rojas Pérez, Isaias. 2008. Writing the aftermath: anthropology and ‘post-conflict.’ In Deborah Poole (ed.), A Companion to Latin American Anthropology, pp. 254-275. Oxford: Blackwell

Ross, Fiona C. 2002. Bearing Witness: Women and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. London: Pluto Press

Shaw, Rosalind. 2002. Memories of the Slave Trade: Ritual and the Historical Imagination in Sierra Leone. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

–2007. Memory frictions: localizing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Sierra Leone. International Journal of Transitional Justice 1:183–207.

–2014. The TRC, the NGO and the child: young people and post-conflict futures in Sierra Leone. Social Anthropology 22:306-325

Theidon, Kimberly. 2012. Intimate Enemies: Violence and Reconciliation in Peru. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Trnka, Susanna, and Catherine Trundle. 2014. Competing responsibilities: beyond neoliberal responsibilisation. Anthropological Forum 24:1-18

Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Sierra Leone 2004. Witness to Truth: Report of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Accessed 12 July 2014.

Vigh, Henrik. 2006. Navigating Terrains of War: Youth and Soldiering in Guinea-Bissau. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Wilson, Richard A. 2001. The Politics of Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: Legitimizing the Post-Apartheid State. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press

Yezer, Caroline. 2008. Who wants to know? Rumors, suspicions, and opposition to truth-telling in Ayacucho. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 3:271-289