Rainer Maria Rilke: Words gently end at the edge of the Unsayable…

—

This morning the weight of generations of violence erupted with the coffee pot in the kitchen. Sometimes the mundane and the profound have a way of colliding – the hurt my ancestors have received and the hurt they have done illuminated by the explosion of the coffee pot in the kitchen.

How to explain that weight to others?

Perhaps we all feel that weight occasionally?

Are (you) buckled by it?

Now? Ever?

Amid the explosion, I ask myself how do we go about our days pretending like everything is normal when it is anything but? Why do we pretend that the weight of generations of violence, and how the law is used to justify and sustain that violence, is acceptable? Perhaps, if we are honest, there is really no day without Hitler.

Today, before I went to the kitchen to break down, I was looking at the legal documents issued to my grandfather and grandmother at the end of the War.

Terrible things are written there in a beautiful cursive script.

Him:

1939 Lager Ostrow

1940/1941 Ghetto Rutki-Kossaki

1942 Lager Zambrow

1943/1944 Auschwitz

1945 Buchenwald

Question: Welche deutsche Dienststelle hat Ihnen die Erlaubnis gegeben, nach Deutschland zu kommen? (Which German department allowed you to come to Germany?)

Answer: S.S.

Like he asked the S.S. for permission to come to Germany.

Her:

1939/1942 Łódź

1942/1943 Auschwitz

1943/1945 Zolern

1945 Theresienstadt

On one document she requests to have her birthday corrected from 8.12.1909 to 12.8.1909.

Action taken: considered a clerical error.

I imagine the bravery of my grandmother having to approach authority after all that has happened to her at the hands of authority to ask for this amendment to be made. An amendment that was just a “clerical error”. Nevertheless, she is thinking, just in case. Just in case it causes problems later on. Just in case it means our resettlement is delayed. Just in case I get punished or separated (or worse) from my husband and children and family, again. Just in case.

Another document, an Action Sheet, prepared in 1948 in the Landsberg Displaced Persons camp, states that my grandfather who “hat seine Familie in Polen verloren” (whether verloren means lost or dead in this context I do not know), “object[s] to any place of immigration except U.S.A. where relatives are living”.

He, and his wife, are sent to Australia.

Violence and the law have a way of inserting themselves into the fabric of life whether we know/like it, or not.

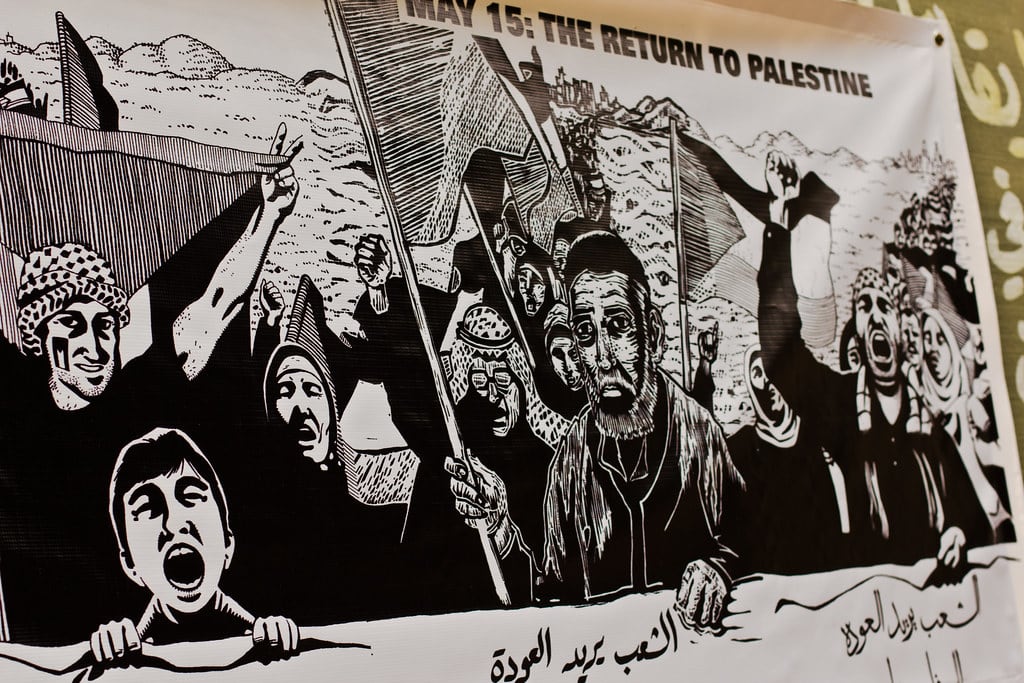

So many photographs of children screaming, the powder of rubble on their faces, blood and small bodies. Some stuck under concrete, others in their parents arms as they weep or look up to the sky to ask for, for what? For help? For humanity? For forgiveness? For rights?

“Israel has a right to defend itself.”

The struggle between the sons of light and the sons of darkness (despite being highly gendered) is bankrupt. I don’t know whose “son” I am anymore when the State whose raison d’être was meant to make Jews safe makes me anything/everything but. Then again, who can deny the weight of the violence inflicted and the scars it causes, that are ripped open, now daily, hourly, every second? Violence, then and now. Recourse to legality, then and now.

I imagine friends approaching Rafah crossing. There are iron fences, concrete blocks, everything highly securitised. In my mind’s eye I cannot decide if they have documents. I want them to have documents, the “right” sort of documents, but I know they are not nationals of another country and therefore, in all likelihood they will not be able to leave. The bombs will continue.

A Whatsapp message: “I am not in a safe place, but still alive. Remember me always. Please take care of my daughters if I die.”

A few years ago, at the Erez checkpoint, a mother is carrying her child who has cancer, on her hip. She is being toyed with by a soldier (who is perhaps 19, maybe 20 years old?). The soldier needs to see a certain document in order to let her pass. She fumbles with her bags and her child. She has many and she does not want to put her child down. She produces the document. No, not that one. Another one is required. The child starts to cry.

In his book Time Maps, Eviatar Zerubavel suggests that while we are, genetically speaking, minuscule parts of our grandparents we are, nevertheless/in spite of/because of, the products of an ‘inherently boundless community’. That inherently boundless community is made up primarily of ‘things below the horizon of history’ (or the “unknown, unknowns” as Donald Rumsfeld once called them). This boundless community is not genes but more social elements like culture, beliefs, skills and aspirations that have passed quietly from one generation to the next. It is also stories of displacement, dispossession, death, trauma, violence, and the law. It is documents that violate our rights, putting us in camps and allowing us to pass through checkpoints, or not. It is the violence done by the State in ways that are (perhaps) legal on paper (or perhaps not). Justified (or not). It is the fear that comes with asking authority to correct an erroneous document. It is being sent to a country where you have no relatives, no connections, no history. It is being told to move south and then being bombed anyway. It is children in neonatal cribs when the power is turned off. It is mothers who sleep with their fingers on the pulse points of their children because they are worried they will die in their sleep from malnutrition.

If we believe, or even simply acknowledge that everyone is in some way or another affected by the inherently boundless community of experiences, and that these experiences – mundane and profound – the coffee pot, the documents, the bombs – craft the shape of all our lives – or at least tie each of us simultaneously to the past and the future – then it is necessary to, and impossible not to, feel mournful empathy for all sentient beings.

We are all wounded,

pulling large sacks of despicable acts,

tied with invisible threads,

behind us like a ball and chain.

Over time the ball and chain affects the way we walk, the way we think, the way we interact with the world. Bringing above the ‘horizon of history’ the ball and chain allows us not so much as to understand, fix and remedy the fact that we carry it, but to see its repercussions and to open our hearts to the woundedness of ourselves and others.

Aurora Levins Morales, a Puerto Rican Jewish poet writes:

We cannot cross until we carry each other,

All of us are refugees, all of us prophets.

No more taking turns on history’s wheel,

trying to collect old debts no-one can pay.

The sea will not open that way.

Sharif S. Elmusa, a Palestinian poet who grew up in al-Nuway’mah refugee camp writes:

I hear. The good helpers are unable to comfort.

The shelter does not shelter.

I want my house to stand.

I want the walls back

To weep alone

To hang pictures.