Yellow Bar, Mukono, Central Uganda; February 2010.

It is Saturday night in Mukono on the outskirts of Kampala city. The bustle of the trading center and market is cooling down, the traffic jams have died out; now the night-time bustle and the jams on the dance floors are beginning all over town. Tonight is Karaoke Talent Night, a hand-painted banner outside Yellow Bar announces. At the bar, young women are sipping Bell lager. At the opposite end of the room, a stage and a DJs booth dominate the wall. The stage is wooden and hovers above the backs of the rows of white plastic chairs in front of it. Black fabric, black paint, simple lights on the middle of the stage.

As 11.30 approaches, the room is filling up. The hall smells of stale beer, urine and sweat; it tastes of it. Most visible are young men, dressed up in “fashion design” clothes—sneakers, jeans and T-shirts with slogans; caps, and jewelry with gleaming plastic gems, moving jerkily with darting eyes. A few older men in meticulously ironed shirts and dress pants are escorted by women with braided or relaxed hair. The room is so big, and much of it is shrouded in a smudgy darkness where groups of men sit and drink, beer bottles crowding their tables, where women dance incitingly with their bottoms parked in the crotch of their male partners.

On the stage two young men in baggy jeans and sweatshirts are struggling to perform the hit song “Ability” by the Ugandan superstars The Goodlyfe Crew. They sing along with the song, but seem not to know the words well and their movements are uncoordinated and aimless, unrehearsed. This displeases the audience, and the Master of Ceremonies (the MC), who is the host of the show, signals the DJ, who stops the music. The MC collects two wireless microphones, as he ushers the two disappointed young men off the stage. “Thank you, thank you, ladies and gentlemen,” the MC says as if to an imagined applause. He has already alerted the next performer, who gets up from his chair, ready, as the others pass him.

We begin within a typical scene from Kampala’s nightlife: young people on a stage, performing songs made famous by others, before an audience. Since the middle of the 1990s karaoke has emerged as a popular from of entertainment and it has given rise to a new generation of music performers and stars in Uganda.

Conventionally we think of karaoke -the Japanese word for “empty orchestra”— as a particular kind of social singing where the singer provides a live vocal to specially prepared versions of popular songs where the lead vocal tracks are left empty. However, in its Ugandan version, karaoke refers to a range of music performance practices that are based on the creative potential of imitation in the technological ”splitting” of sound from its makers, or its source. Urban youths in Uganda perform karaoke in different contexts; at shows like the one at Yellow Bar, in karaoke talent competitions at schools, at parties as well as large music shows at sports grounds and arenas. Karaoke has been pivotal for the development of the informal music industry in Uganda, which some estimates provide livelihood for 100,000 Ugandans, performing, recording, broadcasting, and selling music. Rather than trying to pin down karaoke as a specific type of performance, I will try to explore karaoke as a performance ideology which underpins the contemporary music scene. In the context of a large urban youth population, whose access to education and the formal job market is limited, karaoke somehow has caught the dreams and aspirations of young people, and it points to shifts in the relations between people and popular music in Uganda, as well as to how music making practices indexes notions of self-fashioning and innovation among urban youths in Kampala.

Without wasting time,” the MC beams, standing in front of the stage and gesturing to the next performer, “here is a bit of dance from Mukono’s Michael Jackson.

Hesitant cheering, a moment of empty sound. A young man steps up onto the stage. One hand in glove, shiny black shoes, aviator shades, black soft hat. He stands on the edge of the stage, making him a black silhouette in profile. The three spots are pointed elsewhere. The audience sits expectantly. The music sets him in motion. A medley of greatest hits and greatest-hit moves. The young man snaps his fingers with a flick of the wrist, pops out his skinny chest. That tiny movement is Michael Jackson, no mistake. He grabs the hat in a downwards movement, then places one hand just above his crotch and the other behind him, index and pinky fingers pointed down, moving to the rhythm of Billy Jean. His mouth mimes the lyrics as he skips, slips and slides across the stage. One foot slides behind the other, toe on the wooden surface, then the other, heel down. The effect is peculiar. It looks like Mukono Michael Jackson is walking forward, but he is actually moving his body in the opposite direction—moonwalk. There are cheers. He ends in a kind of clumsy pivot and stands on his toes for a second, grabs his crotch. Mukono Michael Jackson, on stage, mimes Billy Jean (almost perfectly adopted from the Motown twenty-fifth anniversary performance of 1983).

Hesitant cheering, a moment of empty sound. A young man steps up onto the stage. One hand in glove, shiny black shoes, aviator shades, black soft hat. He stands on the edge of the stage, making him a black silhouette in profile. The three spots are pointed elsewhere. The audience sits expectantly. The music sets him in motion. A medley of greatest hits and greatest-hit moves. The young man snaps his fingers with a flick of the wrist, pops out his skinny chest. That tiny movement is Michael Jackson, no mistake. He grabs the hat in a downwards movement, then places one hand just above his crotch and the other behind him, index and pinky fingers pointed down, moving to the rhythm of Billy Jean. His mouth mimes the lyrics as he skips, slips and slides across the stage. One foot slides behind the other, toe on the wooden surface, then the other, heel down. The effect is peculiar. It looks like Mukono Michael Jackson is walking forward, but he is actually moving his body in the opposite direction—moonwalk. There are cheers. He ends in a kind of clumsy pivot and stands on his toes for a second, grabs his crotch. Mukono Michael Jackson, on stage, mimes Billy Jean (almost perfectly adopted from the Motown twenty-fifth anniversary performance of 1983).

The Rise of the Karaoke Generation

Considering the rich musical heritage of Uganda and its history of storytelling, singing and playing on instruments, the performance of Mukono Michael Jackson may seem quite alien to what is thought of when the words “Uganda” and “music” are put together.

The localkaraoke-scene, as it was told by my friends in Kampala, emerged in the middle of the 1990s as Kampala became more peaceful and secure after decades of civil war and unrest, and its residents began venturing beyond their own neighborhood and into the nightlife of the city. This was concurrent with the liberalization and privatization of the media economy. Commercial radio stations, and small cassette dubbing enterprises mushroomed. The foundation for the new market for popular music was partly its informality, which enabled the commodification of music in flexible and inventive ways by local music enthusiasts who had little access to start-up capital, while keeping international potential investors and recording companies afield.

The market for popular music was grew explosively, and there was a high demand to experience the global urban genres that were hitting on the new local FM stations live. Urban teens stepped onto the local stages to entertain each other. Karaoke was a way of participating on the nightlife scene, “to get a chance on how it feels to be a star,” as a newspaper reported on one of the very first karaoke talent nights back in 1996. And this became a vantage point for youths to imagine and practice popular music in Kampala.

Lyrical G was one of the young people who started his musical career as a karaoke performer in the mid-1990s. The advent of commercial radio increased the availability of American and Jamaican popular music genres like dancehall, hip-hop and R&B, and this changed Lyrical G’s relationship with music, he said, as we hung out in a roadside bar on a lazy Kampala afternoon:”For me, getting into this hip-hop ting (… ) [is] ‘cause I’m a fan first and foremost. ” He explained how he and a group of friends became inspired by American rappers like Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, and took turns to perform their songs at high school dances and local bars. Karaoke in this way allowed aspiring singers to get on stage and “do” music without having to hire a backing band, acquire expensive technological equipment, or pay studio fees to record self-composed songs.

Lyrical G and his group now attracted their own following of fans, becoming regular performers in various different night time venues throughout the week in the city. Initially, they were not paid to perform, except from the tips and drinks offered by fans after performances, but as their popularity grew, bar owners and promoters started offering them money, because their names on the list of performers would ensure an audience and clientele in their venues. A new generation of musicians was on the rise.

Lyrical G and his group now attracted their own following of fans, becoming regular performers in various different night time venues throughout the week in the city. Initially, they were not paid to perform, except from the tips and drinks offered by fans after performances, but as their popularity grew, bar owners and promoters started offering them money, because their names on the list of performers would ensure an audience and clientele in their venues. A new generation of musicians was on the rise.

In the early 2000s digital music recording came to Kampala, and within a few years hundreds of music studies popped up in the city. Lyrical G called his first recording of his own songs his ”graduation”:

After a while, I graduated to writing my own stuff. And then recording it, getting my own stage, doing these concerts. (… ) And I had already made a name, appearing on stage and rapping. I stopped doing other people’s songs. Now I was writing my own small little-little raps.

Lyrical G became one of the few who made a name for himself as a hip-hop artist in Uganda by rapping convincingly in English, while most of his contemporary karaoke “graduates” sung and chanted in the local language Luganda or Swahili. He built a steady following of fans among fellow hip-hoppers, and later won several music awards, besides travelling the East African region and beyond performing his music.

Lyrical G exemplifies a success trajectory for a musical career among the karaoke generation—from being a fascinated fan of global music stars, to being inspired to take on the stars’ stage personas doing karaoke (of the same stars), to graduating to creating one’s own songs and recording them, thus identifying oneself with the same genre as the global stars who were the inspiration to step on stage.

Though they had their own material, the generation of singers who had started their music careers as karaoke performers continued to perform karaoke-style, singing along with or miming their songs on CDs. Karaoke in this way represents a way for young Ugandans to participate in global youth cultures, forging trajectories for inserting oneself in a potentially global “star system” of artists and celebrities. Put simply, the karaoke generation modeled their artistic identities and their hopes for future trajectories on the stars they mimed. Karaoke as a novel kind of performance ideology form the 1990s onwards changed not only local popular music genres, but also who a musician could be, as young mimers embodied North American and Jamaican pop icons like Michael Jackson, Celine Dion, Mariah Carey, Snoop Dogg, Shabba Ranks and Buju Banton.

Shifts in performance ideologies

After independence in 1962, popular music took center state in the cultural politics of Uganda. The new nation turned away from what was seen as colonial culture, imitating European styles and genres, and turned its efforts to establishing a distinct national identity for a modern African state. The state actively embraced music and dance as part of ideologies of “Africanization” or “de-Westernization”. In Kampala, jazz bands performing “dance music” became the hallmark of the new independent Ugandan culture, as they took inspiration American jazz, Latin American rhythms and Central African styles, playing African rumba with either Lingala (Congolese) or Luganda lyrics promoting and celebrating independence and pan-Africanism.

The story of Afrigo Band, known as Uganda’s longest running “dance band”, reflects the performance ideologies of the post-colonial era in Kampala. Starting out in 1976 as an offshoot of one of the most popular jazz bands in the city, Afrigo Black Power Bandtied themselves into pan-African independence ideologies. Their music repertoire and performances sought to express ideals of “Africanization and unity,” as a band member told me, “trying to make a single rhythm that unites us.” Afrigo Band in the 1970s became one of the most popular groups in Uganda, performed for – and was promoted by – the (in)famous president Idi Amin, and their music was in heavy rotation on the national radio channel. Jazz bands like Afrigo used foreign technologies, languages and musical elements to create music that captured the ears and imagination of wide audiences, promoting political messages and speaking to and for “the people” in the spirit of Uganda as an independent state.

Afrigo continues to be a popular band in Kampala, drawing a steady audience to their regular weekly performances. Jazz bands in Kampala, like in other parts of East Africa, are large ensembles, typically performing with ten to twenty people on stage. Bands also include understudies; second- and third-string band members. Music performances may last five or six hours, and in this time, instrumentalists, singers and dancers take turns on stage; building up the emotional space of the room. In these performances members of the band and the audiences interact, as the band leader or singers recognizes the presence of dignitaries on the microphone, take requests, and modify lyrics of songs to fit the events going on in the dancehall; as dancers engage the audience; as members of the audience may engage fellow audience members by singing along or dancing to particularly significant passages of a song.

Emphasis here is on different forms of reciprocity as performers and audiences collectively constitute the performance space. These different forms of exchange, within bands, and between the band and the audience, constitute a kind of circulatory performance ideology in which participants my take up different positions in the course of a single performance.

Musicians also move between bands, and older musicians recall how they in the 1960s and 1970s circulated between Kampala, Nairobi, Dar Es Salaam and even Kinshasa, playing with different ensembles and working as studio musicians. Individual musicians rose to fame as members of bands, and audiences would praise the talents of their favorite guitarists or singers, yet the stable institutions and names in the music scenes were the bands.

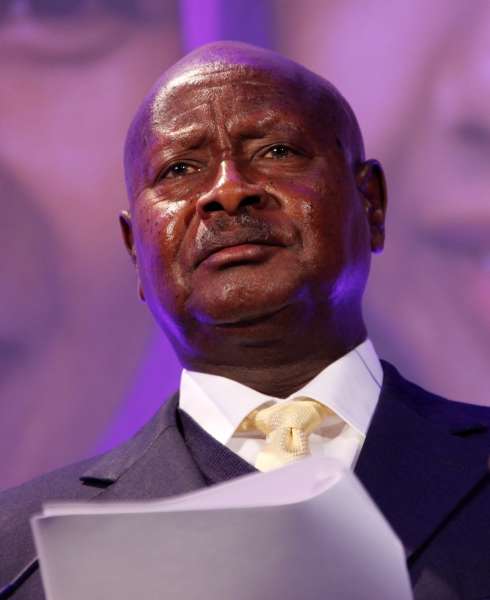

Post-colonial Uganda also faced musicians with the shadow side of state patronage. With the rapidly deteriorating economy and increasingly volatile living situation in Kampala, Afrigo band remained active by forging client-ties to Idi Amin’s regime, but many prominent musicians went into exile. The situation was only made worse after the overthrow of Idi Amin in 1979 and the contested election in 1980, as the rebel group National Resistance Army led by Yoweri K. Museveni went to war. Older musicians and entertainment reporters, I talked to, said that by the early 1980s only a handful of bands were playing in Uganda, and public nightlife was restricted by curfews and insecurity for people moving beyond their immediate neighborhoods.

Museveni’s slogan, as the National Resistance Army/ Movement (NRA/M) came into power in 1986, was that his rule was not only a change of guards but a “fundamental change.” The new regime set out to make Uganda democratic and to ensure its citizens a decent standard of living. Museveni explicitly emphasized participation in the market and individual entrepreneurship as a way to get there. In his biography, “Sowing the Mustard Seed” from 1997, he writes about the majority of Uganda’s population as peasants trapped in the backwater of underdevelopment. The peasant “is not worried about markets because he has little to sell. (…) The hill is the outer limit of his horizon.” The public discourses of the NRM regime where bodying forth an image of citizens as the opposite; participants in the marketplace with their eyes not on the hills of the neighbors farm, but on global horizons. The NRM and Museveni’s rule in practice represented a shift towards liberalization and privatization through structural adjustment programs and economic to reform. The hopes of a market driven economy were encapsulated in the slogan “prosperity for all”. The “fundamental change”was also felt in popular music.

Museveni’s slogan, as the National Resistance Army/ Movement (NRA/M) came into power in 1986, was that his rule was not only a change of guards but a “fundamental change.” The new regime set out to make Uganda democratic and to ensure its citizens a decent standard of living. Museveni explicitly emphasized participation in the market and individual entrepreneurship as a way to get there. In his biography, “Sowing the Mustard Seed” from 1997, he writes about the majority of Uganda’s population as peasants trapped in the backwater of underdevelopment. The peasant “is not worried about markets because he has little to sell. (…) The hill is the outer limit of his horizon.” The public discourses of the NRM regime where bodying forth an image of citizens as the opposite; participants in the marketplace with their eyes not on the hills of the neighbors farm, but on global horizons. The NRM and Museveni’s rule in practice represented a shift towards liberalization and privatization through structural adjustment programs and economic to reform. The hopes of a market driven economy were encapsulated in the slogan “prosperity for all”. The “fundamental change”was also felt in popular music.

The new generation of musicians taking the stages from the 1990s and onwards, actively fashioned themselves as individual figures, rather than as a part of a circulation of positions within a group. Here karaoke is a central site for drawing forth the performer’s singular and individual talents and potentials through the imitation of global music stars.

Bobi Wine, who has been one of the most successful singers on Kampala’s music scene over the last ten years, said in an interview about his early days as a teenage karaoke singer in the slum:

Originally we did not have a style. Ugandan music was not listened to, only Congolese [dance] music. But there was a time, especially with the influence of Chaka Demus and Pliers; the dancehall, that wave that came… It was similar to ours, yet different. The vibe was the same—that syncopated beat. It was—it was African yet it had a foreign style (… ) That helped us discover ourselves. And we’ve been developing styles and we’ve been identifying abilities in us.

The American stars on the black music scene and the Jamaican dancehall artists breaking through internationally in the mid- 1990s emphasized their artistic identities as entrepreneurs, fashioning themselves as “brand names” and consumer products. Global pop stars and their status as celebrities increasingly became “an advertisement for a new gilded age when commodities overpower everything, (…. ) reducing hitherto insoluble problems to the dimensions of the market,” as Ellis Cashmore wrote about global celebrity culture in 2010. These global superstars became models for ways of performing value and fame among urban youths in a Uganda where the president and the ruling party in slogans promised “prosperity for all” through economic liberalization and growth.

In karaoke, a singer becomes more than an entertainer at parties and social gatherings, or a mouthpiece for “the state” or “the people”— a singer is someone for and of her or himself. The global genres hip-hop, R&B, and cross-over dancehall fashioned the singer as a star; singular solo performer on the stage who could not be replaced or substituted by another. The karaoke singers did not call themselves musicians: they were artists. Singing and doing music to “feel like a star” and to be an artist were distinctive new ways for young people to engage with popular music. The circulatory dynamics of popular music in “dance music” and jazz bands was by my interlocutors seen as fundamentally different from the performances karaoke generation. My younger friends in the music industry recognize the legacy of Jazz bands, some of which continue to be popular in the new millennium. But they emphasize that where bands retain their following by what they themselves call “circulating” their hit songs, playing the same repertoire over several years, the stars of the young generation have to constantly perform new hits and new styles to keep and attract their fans, to keep “selling.” The musicians of the karaoke generation became artists, stars and entrepreneurs, by experimenting with how their music, and they themselves could be traded as products in the local music economy, seen as embedded within global music industries.

In this sense, it is apt to think of karaoke as a performance ideology available to youths in Kampala, shaping trajectories from fandom to stardom, creating novel kinds of subjectivities and relations in the city.

The generation of singers who started their careers performing karaoke has fundamentally different experiences with and understandings of popular music than the musicians of the dance and jazz bands that went before. Young people’s self-fashioning in karaoke as artists and stars, with products to sell to consumers, has been fundamental for the emergence of the new music scene and the thriving music economy in Uganda.

During the performance, several audience members walk up to the stage to shove a token of appreciation into Mukono Michael’s hand. Some of the women stop in front of the stage to dance for a moment before they return to their seats. The tippers give to the performers they think are talented. Mukono Michael’s emaciated body lends him credibility as his legs in the too-short black pants jerk rhythmically into awkward positions. Mukono Michael’s friends cheer him on, as the music ends. Smiling and giving out high fives, Mukono’s Michael Jackson takes off his shades and the hat, and stuffs the coins and 1000 shillings notes into his pockets, before he and his friends disappear into the dense night. The MC prepares to announce the next act on stage in Karaoke Talent Night. Girls are still dancing, groups of friends still drinking and laughing in the corners.

Excited about popular music in Africa? Here are some great reads:

Askew, Kelly (2002). Performing the nation: Swahili music and cultural politics in Tanzania. University of Chicago Press.

Perullo, Alex. (2011). Live from Dar es Salaam: popular music and Tanzania’s music economy. Indiana University Press.

Shipley, Jesse Weaver (2013). Living the hiplife: celebrity and entrepreneurship in Ghanaian popular music. Duke University Press.

White, Bob W. (2008). Rumba Rules: the politics of dance music in Mobutu’s Zaire. Duke University Press.