“That’ll be $1.09.” I hand over the last two dollars of my stipend in exchange for my favorite kind of cookie, a gingersnap, while the bakery owner and I Chat. “Where are you from?” he asks. “Back east.” He nods knowingly, “here for work then?” Explaining that I’m here for research and split my time during the year between Tennessee, where my university is located, and San Francisco, my field site locations, is a bit too complicated and cumbersome for this particular conversation. I really just want the cookie before beginning the day’s research activities, so I answer with a simple affirmative. He nods, then sighs. “People used to come here and fall in love; they’d stay forever. Now it’s only people that work for a few years and then leave.” “Because of the start-ups?” I ask. “Yeah. The neighborhood has changed a lot during the past few years.” He hands me the change and gingersnap and quickly gets back to work.

Although the symbols and memories of San Francisco’s complex and important place in political and social history still stand, the city has undergone a series of rapid transformations throughout the past few decades.

Today the San Francisco Bay Area is a central site for start-up companies, especially those seeking to push boundaries, to break the norm. The area features a diverse array of start-ups, including Experiment, Parenthoods, Funding Circle, HackerOne, and Lumoid, just to name a few. The start-up world attracts people from all over the country and the world who have the technological skills to power innovative ideas. As a result, young, single, highly-educated people journey to the Bay Area, dramatically altering skylines, demographics, and the character of communities. The Bay Area offers the possibility of gaining skills and experience tech workers can’t get anywhere else, but will make them indispensable employees in other sectors of the market. As the baker correctly identified, the workers often plan to stay a few years, just until their start-up goes public or they can snag a higher paying Job elsewhere. But San Francisco is not a city of skyscrapers and high rises; instead, most housing consists of early 1900s styles, when the ability of engineering to adequately create buildings suited to frequent earthquakes limited the number of floors possible. Low housing supply and high demand from renters and prospective homeowners has skyrocketed the price of homes and rent in the Bay Area, transforming the city and its communities. Home cost and rent increases, with rent prices hitting a record high in April, and continued gentrification, turning formerly low-income and working class areas populated by minority communities into “up-and-coming” areas for young city newcomers, are some of the far-reaching effects. Recent years have seen many demonstrations protesting the move of tech workers into city limits, seen as the driving force of gentrification and its associated effects.

Gentrification and the drive to “renew” areas of the City are an important part of various journeys: the journey of the tech industry and the individuals it attracts into the City and of the urban poor and working class further from it.

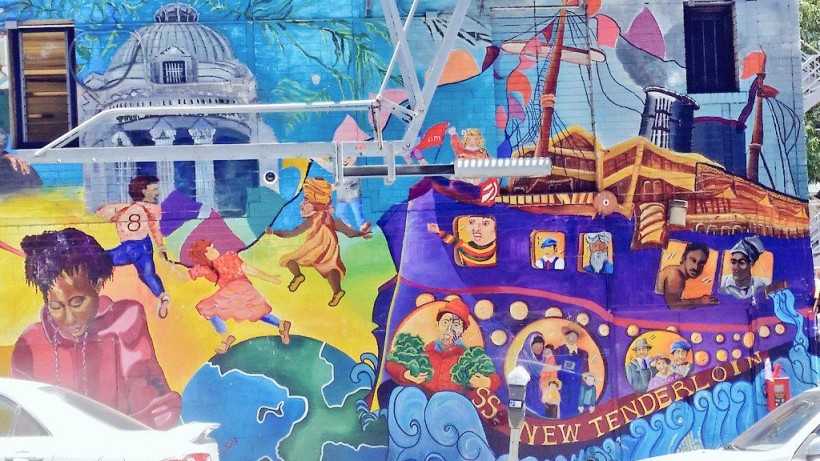

In many ways my research and the efforts of the justice practitioners and clients I work with illuminate the journey of tech industry, its employees, and journeys of the urban poor. This two part series of articles is dedicated to the various journeys experienced by San Francisco Bay Area residents – examining the implications of gentrification, renewal, and subsequent migrations for contemporary justice practice. Evidence of transformations and associated journeys are visible throughout the city. From my building, a typical early 1900s build that steadily rocks back and forth during earthquakes, I can quickly walk through some of the most expensive areas of the City, such as Pacific Heights and Nob Hill, to the Tenderloin, one of the poorest. Pac Heights and Nob Hill are home to some of the City’s steepest hills, offering spectacular views. The streets are lined with neatly manicured trees and houses that have been carefully restored and maintained. The areas are largely inhabited by White, upper-class, and the well-to-do. Just a few blocks away lies the Tenderloin (lovingly referred to as the “TL”). The TL is one of the last outposts for low-income, working class, and homeless people living in the City and, like the Mission before it, the TL is being gentrified by newcomers. The TL is a vibrant area home to predominantly African American and Vietnamese populations. Day or night, the area is teeming with people, especially on Leavenworth, where the photo above was snapped. Corner markets, restaurants, small shops, and cheap housing are readily available. Poverty is visible from the odd assortments of items for sale on the street to the carts of belongings slowly pushed along and trash left on the street with no vigilant neighborhood association to pick it up. Homelessness, drug running, and gang activity are easily discernible here, but so is community. Just before I snapped the photo below, a stranger greeted me with a cheerful “good morning;” a rare occurrence for those accustomed to urban life. Community and poverty, often characterized as dichotomous concepts by those seeking to gentrify or “renew” are not in juxtaposition. Rather, they are intertwined in complex webs of relationships that create the vibrant TL.

However, the TL is on a journey towards gentrification – variously characterized as revitalization, urban renewal, and Negro removal, depending on who you ask. Regardless of what we call it, the S.S. New Tenderloin is here. Over the past few years of fieldwork, new neighborhood names discursively mark areas of gentrification have crept into vernacular. TenderNob, an amalgamation of Tenderloin and Nob Hill, marks the area between the low-income and well-to-do neighborhoods, respectively. Uptown Tenderloin, not far from the TenderNob, displays banners that boast the 409 historic buildings in 33 blocks, attempting to transform associations of the TL with poverty, drug use, and gang activity, to characterizations of the area as a place of economic stability and historical significance. The Uptown TL organization asserts the changing nature of the area:

“Uptown Tenderloin has long been known as the “heart” of San Francisco. It has been the last refuge for seniors, disabled persons, and low-income working people striving to stay in the city, and the community where newly arrived immigrants seek a fresh start. The neighborhood is now being transformed into an exciting and desirable area where restaurants, theaters and other small businesses prosper, and low-income people of diverse ethnicities can still afford to live.”

The “transformation” of the TL is characterized as a revitalization that will save the historic buildings and recover the historic significance of the area. As Hispanic populations are continually pushed out of the Mission by tech workers journeying into the City and looking for a hip place to live, the TL and its inhabitants may suffer a similar fate. As the new journeys in, the old either attempts to stand is ground or begrudgingly moves out.

A similar and familiar story, the story of Twitter, encapsulates the gentrification in Central Market, a stone’s throw away from Uptown TL. In 2011, Twitter agreed to maintain their company HQ in San Francisco in exchange for tax breaks and taking over a rundown building in Central Market as part of a revitalization attempt. At the time, Central Market was a “blighted” area of the city where homeless and low-income individuals resided. Catholic Charities assisted housing is still just a couple blocks from what is now Twitter HQ. Efforts to revitalize Central Market are taking effect; NEMA, one of San Francisco’s most expensive apartment complexes, is now Twitter’s across the street neighbor, and pricey eateries, including a swanky candy shop, are taking over.

In San Francisco, poverty and wealth live side by side in an uneasy and often antagonistic relationship. Longtime residents note the skyrocketing rent prices in places traditionally considered cheaper, such as Berkeley, Oakland, the Mission, and the TL.

The working class and those paid below the median income necessary to live where they work are continually pushed further and further out. For example, the security guard at Google who lives in San Jose and commutes to work every day. Similarly, the conflict resolution practitioner working for social justice who commutes by car more than an hour to and from work, because they are paid thousands less than is necessary to meet basic living expenses where they work. Stories of sad journeys out of the city are as common as the joyful journeys of the incoming. Narratives of gentrification and its effects, tensions between longtime residents and newcomers, and the uneasy relationship of the poor to their rapidly transforming city are clearly evident in my fieldwork on alternative justice models – those existing outside the purview of the formal legal system.

“I need help. I’ve got this neighbor and he’s just doing drugs and bringing people over and he’s so loud! I can’t take it anymore. What are you going to do for me? ‘Cause I need this issue resolved.” The man speaking with me self-identifies as in his 40s, White, and poor. His clothes are shabby and unclean and he has the smell of someone who hasn’t bathed in several days. Solidly built with wide shoulders and a barrel chest, he looks like he belongs on a football or rugby field rather than in the shiny downtown office. He looks at me earnestly, waiting for a response as to how this conflict resolution organization can help him. “Where do you live?” “I live in an SRO a little ways from here” he replies. I nod, at this point not unfamiliar with single room occupancy housing, though I am surprised I haven’t seen more cases from individuals living in this form of housing. We begin discussing his perception of his neighbor, who he believes is a drug addict, bringing prostitutes and friends over constantly, and causing a ruckus in the building. As we speak, I realize that after several months of work in offices like this one I have only rarely been confronted with individuals facing these issues. Rather, I have seen case after case of individuals concerned about property lines, tree maintenance, and noisy neighbors. When I first embarked upon this project, I thought I would be studying with the marginalized – those that need the access to justice programs based on factors such as race, class, and language barrier. I quickly realized that many of these programs and practitioners serve the middle class, the landowners, resolving conflicts about property lines, parking, and noise.

Make no mistake, these are important conflicts to resolve, but perhaps it took the barrel-chested man who hadn’t bathed asking for help with his neighbor to truly realize what is happening in my field site. Programs ostensibly created to increase access to justice do not always reach the individuals who most need their services. Driven by resource constraints, they nearly never reach the most marginalized communities in the Bay Area. It took the jarring juxtaposition of that one client sitting in the bright office surroundings for me to realize the unanticipated journey of my research project – from access to justice for the marginalized to something else – had taken and the implications of that for the journey of informal justice practice and its stakeholders.

This post was first published on 24 June 2015.